Paul Revere: More Than Just a Midnight Ride

BOSTON – Cloaked in the velvet twilight of April 18, 1775, a lone horseman galloped through the Massachusetts countryside, a phantom figure whose urgent message would ignite the American Revolution. His name was Paul Revere, and his legendary "midnight ride" has been etched into the bedrock of American folklore, immortalized by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s stirring verses. But the Paul Revere we know from the poem – a singular hero, reaching Concord to sound the alarm – is but a romanticized sliver of a far more complex, industrious, and influential patriot. Beyond the iconic dash, Revere was a master craftsman, a shrewd entrepreneur, a meticulous intelligence operative, and a tireless advocate for American liberty, whose life story paints a vibrant portrait of a nation in its infancy.

Born in Boston in 1735, Paul Revere was the third of 16 children to Apollos Rivoire, a French Huguenot immigrant who became a successful silversmith, and Deborah Hitchborn, a local woman. Revere inherited his father’s industrious spirit and quickly mastered the demanding craft of silversmithing. His shop on North Square became a hub of colonial life, producing not just elegant tea sets and intricate buckles for Boston’s elite, but also surgical instruments, frames for spectacles, and even false teeth. This early career laid the foundation for his later ventures, demonstrating an innate talent for precision, design, and practical innovation.

"My father was a goldsmith, and I was bred to the same business," Revere meticulously noted in one of his later accounts, a testament to the pride he took in his craft. His silversmithing wasn’t just a trade; it was a window into the political currents of his time. As a prominent artisan, he was privy to the whispered conversations in taverns and the hushed meetings of revolutionary cells. Boston, a hotbed of anti-British sentiment, became Revere’s crucible.

As tensions with Great Britain escalated in the 1760s, Revere’s patriotism blossomed. He became an ardent Son of Liberty, a secret society dedicated to resisting British tyranny. His workshop, often a gathering place for patriots, was less a clandestine lair and more an open secret where the seeds of revolution were sown. Revere’s unique skills found a new purpose in the burgeoning political landscape. He turned his engraving tools not just to decorative plates, but to powerful political propaganda. His most famous engraving, "The Bloody Massacre in King-Street," depicting the Boston Massacre of 1770, was a masterstroke of revolutionary imagery. Though historically inaccurate in some details, it vividly portrayed British soldiers firing on innocent Bostonians, effectively galvanizing colonial anger and turning public opinion against the Crown.

But Revere’s contributions went far beyond art. He was a crucial cog in Boston’s elaborate intelligence network. He regularly rode as a messenger for the Boston Committee of Correspondence and the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, often traveling to New York and Philadelphia, carrying vital dispatches and relaying crucial information about British troop movements and colonial resistance efforts. These pre-1775 rides, though less celebrated, were arguably as important as his most famous one, honing his skills as a clandestine operative and a swift, reliable courier.

As the spring of 1775 approached, the atmosphere in Boston crackled with an ominous energy. British troops occupied the city, and rumors of a planned raid on colonial military supplies in Concord grew louder. Dr. Joseph Warren, a leading patriot and close friend of Revere, received intelligence that the British planned to march on Lexington and Concord to seize munitions and arrest revolutionary leaders Samuel Adams and John Hancock.

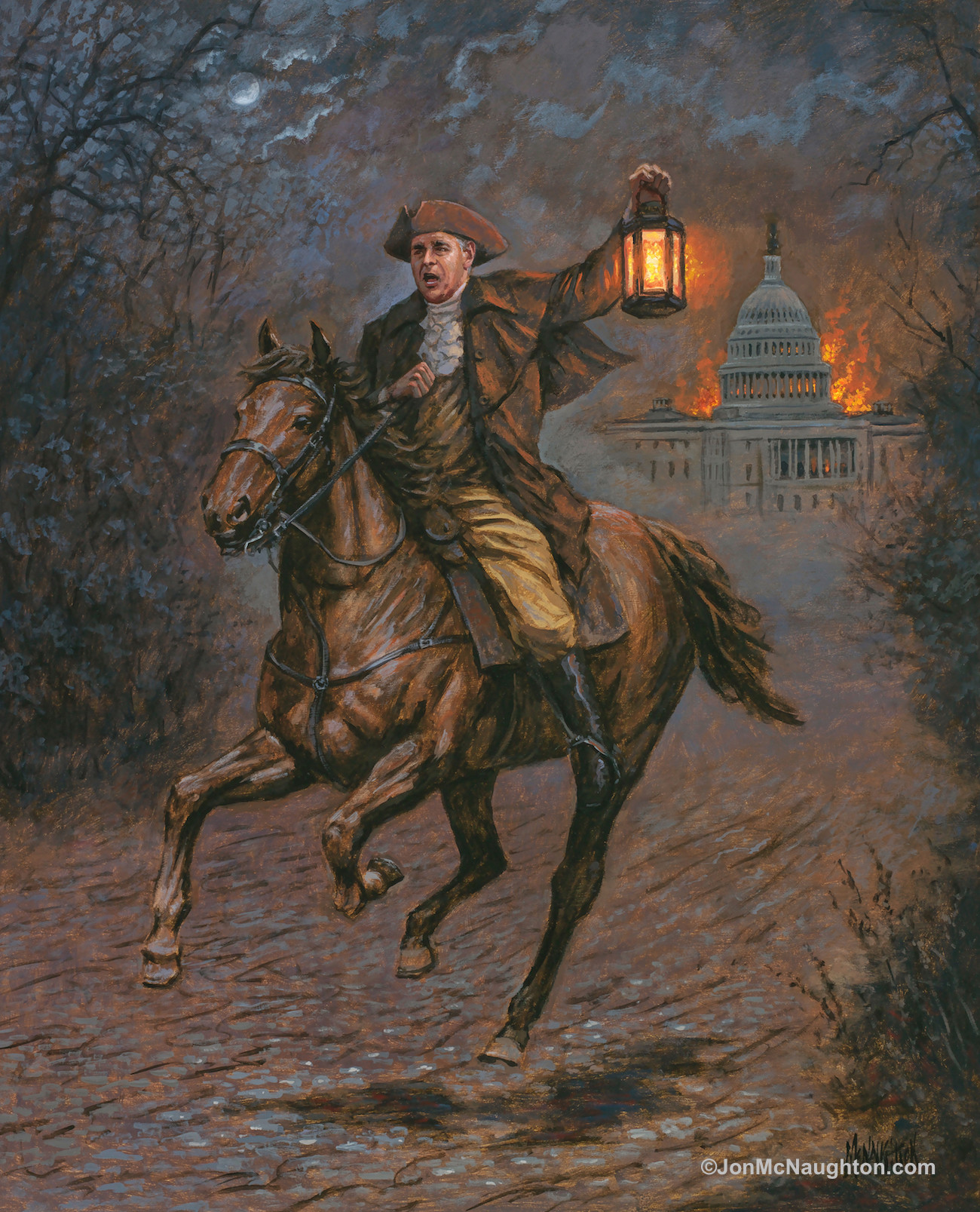

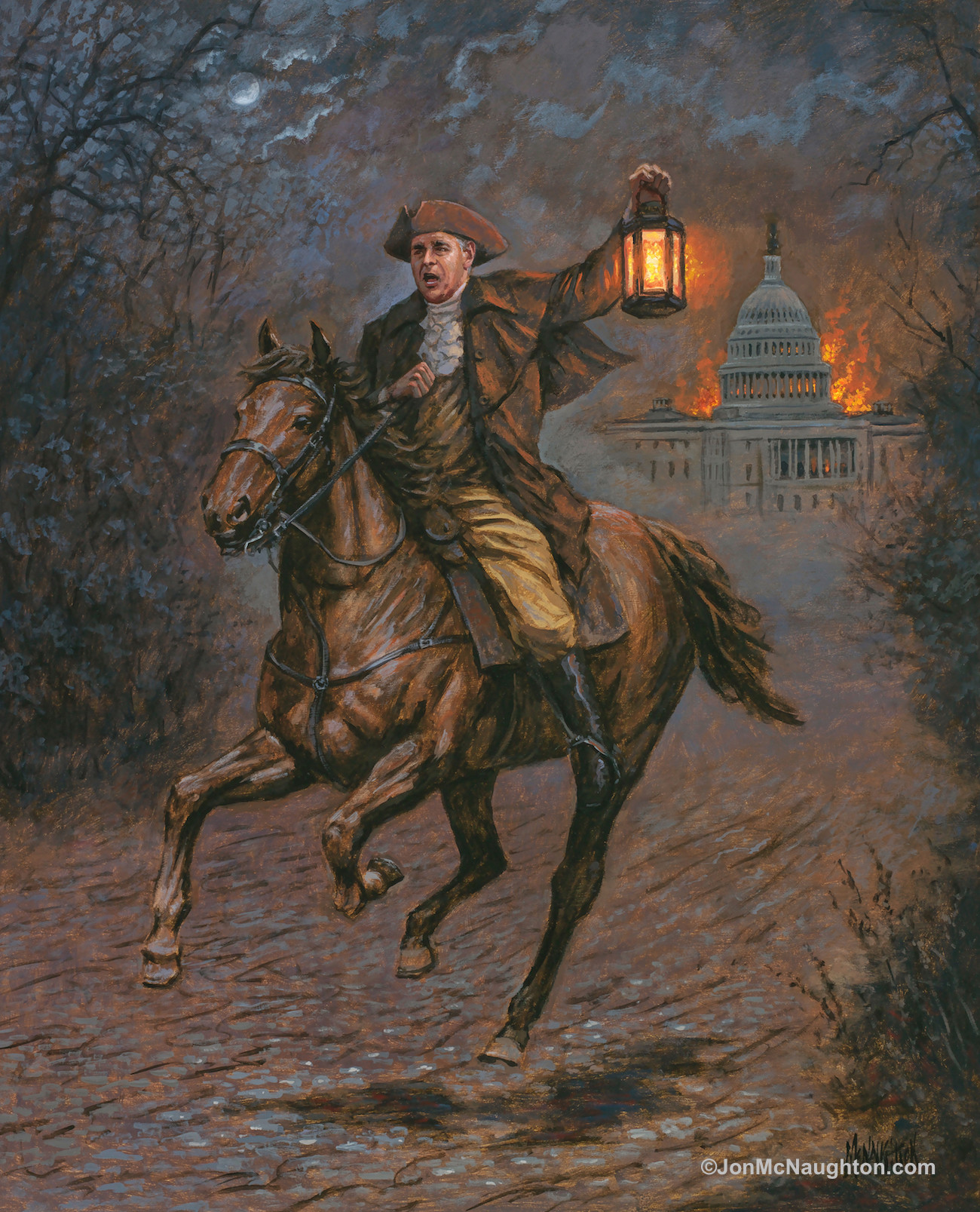

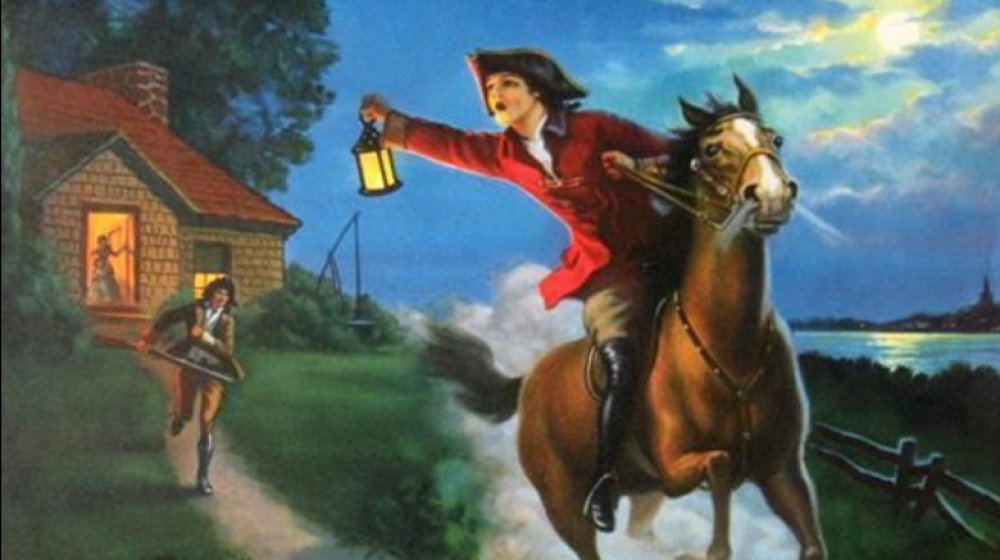

On the evening of April 18, Warren entrusted Revere with a perilous mission: to ride to Lexington and Concord to warn Adams and Hancock, and to "alarm the country." Revere, ever the strategist, had already arranged a system of signals with Robert Newman, the sexton of the Old North Church. "One if by land, and two if by sea," the lanterns would signal from the church steeple, indicating the British route out of Boston. At around 10 p.m., two lanterns gleamed from the belfry – the British were coming by sea across the Charles River.

Revere wasted no time. He was rowed across the river to Charlestown, where he secured a horse, "Brown Beauty," and set off. His ride was not a solitary one. William Dawes, another Son of Liberty, took a different route out of Boston, and later, Dr. Samuel Prescott joined them. Together, they fanned out, waking colonial militias with the urgent cry, "The Regulars are coming out!" – not "The British are coming," as the colonists still considered themselves British subjects.

Revere’s own account of the ride, given later, is a testament to his determination: "I set off upon a very good horse; it was then about 11 o’clock, and very pleasant. After I had passed Charlestown Neck, and got nearly opposite where Mark was hung in chains, I saw two men on horseback, under a tree. I passed them, and heard them say, ‘There rides a man who will give us a good account of ourselves.’"

The journey, however, was not without incident. Shortly after leaving Lexington, where he had successfully warned Adams and Hancock, Revere, Dawes, and Prescott were ambushed by a British patrol. Dawes and Prescott managed to escape, but Revere was captured. He was interrogated, held for a time, and eventually released when the British officers, hearing the sounds of alarm bells and distant gunfire, decided they needed to hasten back to their main column. Revere, left without his horse, walked back to Lexington and witnessed part of the battle that erupted there. He had not, as Longfellow would later suggest, ridden all the way to Concord.

Longfellow’s 1861 poem, "Paul Revere’s Ride," published on the eve of the Civil War, solidified Revere’s place in American mythology. It transformed a collaborative effort into a singular heroic feat, an inspiring tale of courage and vigilance that resonated deeply with a nation on the brink of another conflict. While it romanticized and simplified the events, its power to instill patriotism and memory cannot be overstated. "Listen, my children, and you shall hear / Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere," became a rallying cry, ensuring that the essence of his message – an urgent call to arms against tyranny – would forever be etched in the national consciousness.

Beyond the ride, Revere’s life continued to be one of remarkable dynamism and contribution. His military career, while not as illustrious as his ride, saw him serve as a major in the Massachusetts militia. He commanded Castle William, a fort in Boston Harbor, but faced court-martial for insubordination during an ill-fated expedition to Penobscot in 1779. Though acquitted, the incident was a stark contrast to his earlier heroic image.

It was in the realm of industry and innovation that Revere truly shone in the post-war era. With peace, he channeled his entrepreneurial spirit into a diverse array of ventures. He opened a hardware store, sold spectacles, and even provided copper plating for naval ships. Recognizing the nascent nation’s need for self-sufficiency, he embarked on ambitious industrial projects. In 1788, he established a foundry that produced church bells, cannons, and fittings for ships, eventually casting hundreds of bells that still ring across New England today.

His most significant post-war achievement was the establishment of the first successful copper rolling mill in North America in 1801. He developed innovative techniques to roll sheet copper, a vital material for shipbuilding, coinage, and architectural uses. This mill, located in Canton, Massachusetts, supplied the copper for the dome of the Massachusetts State House and the sheathing of the USS Constitution, "Old Ironsides." Revere’s ingenuity helped reduce America’s reliance on imported European copper, solidifying his legacy as an industrial pioneer and a true captain of early American manufacturing.

Paul Revere died in 1818 at the age of 83, a wealthy and respected citizen of Boston. He left behind a large family and an enduring legacy, though the full breadth of his contributions would only be fully appreciated by historians much later. His life was a microcosm of the revolutionary generation: a testament to self-reliance, adaptability, and an unwavering commitment to the ideals of a new nation.

The legend of Paul Revere, the lone rider, continues to captivate. It is a powerful symbol of vigilance and the courage to act in the face of tyranny. But the man behind the legend was far more interesting – a multifaceted genius whose life was a tapestry woven with threads of craftsmanship, political activism, strategic intelligence, and industrial innovation. He was not just a messenger; he was a vital architect of the American spirit, a patriot who, in every facet of his long and productive life, embodied the nascent nation’s drive for liberty and progress. Paul Revere, the complete man, stands as a testament to the fact that sometimes, the true hero is even greater than the myth.