The Crucible of a Nation: How the Old Northwest Territory Forged America’s Future

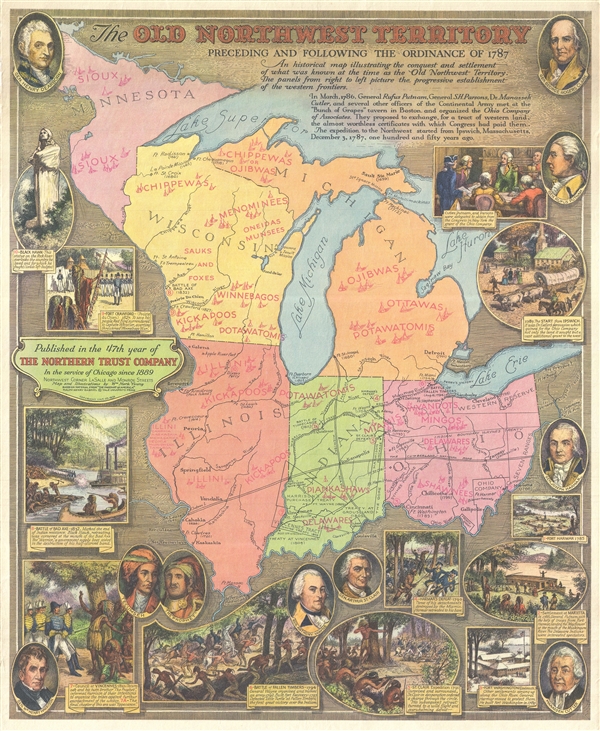

In the vast, verdant expanse stretching from the Appalachian foothills to the Mississippi River, a foundational drama unfolded in the nascent American republic. This was the Old Northwest Territory, a land of ancient forests, mighty rivers, and boundless promise. More than just a geographical designation, the Northwest Territory, encompassing modern-day Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and a portion of northeastern Minnesota, became a legislative crucible. Here, the fledgling United States hammered out the very blueprint for its westward expansion, laying down principles of governance, land ownership, and even the moral compass regarding slavery that would shape the nation for centuries to come. Its story is one of visionary legislation, brutal conflict, and the enduring struggle to define what it meant to be American.

The tale begins in the immediate aftermath of the American Revolution. With the Treaty of Paris in 1783, Great Britain ceded a massive tract of land west of the Appalachians, but this victory brought a new set of challenges. Several states, notably Virginia, Connecticut, and Massachusetts, held competing claims to portions of this vast territory, based on colonial charters that vaguely extended their borders "to the South Sea." This territorial squabble threatened to tear apart the fragile confederation of states. It was a moment of profound national peril, where the centrifugal forces of state sovereignty vied against the nascent idea of a unified republic.

"The relinquishment of these claims by the individual states was a crucial step," notes historian Frederick Jackson Turner in his seminal work on the American frontier. "It transformed a collection of squabbling sovereignties into a nation with a common domain, a public estate to be administered for the common good." Virginia, holding the most extensive claim, magnanimously ceded its lands in 1784, largely due to the foresight of leaders like Thomas Jefferson, who envisioned an empire of liberty rather than an extension of existing states. This act of collective sacrifice paved the way for the most significant legislative achievements of the Confederation era: the Land Ordinance of 1785 and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787.

The Land Ordinance of 1785 was a revolutionary act of cartographic and economic engineering. Faced with a burgeoning national debt and a desire to impose order on the wilderness, Congress devised a systematic method for surveying and selling public lands. It imposed a rational, geometric order on the untamed landscape. The territory was to be divided into townships, each six miles square, and further subdivided into 36 sections, each one square mile (640 acres). These sections were then sold at auction, often for a minimum of $1 per acre.

Crucially, the Ordinance stipulated that "Section 16 of every township, shall be reserved for the maintenance of public schools within the said township." This single provision, seemingly mundane, embedded the principle of public education into the very fabric of westward expansion. It declared, in effect, that as America moved west, civilization, enlightenment, and democratic participation would follow, not as an afterthought, but as a foundational pillar. This was a radical departure from European colonial practices and an enduring legacy that shaped the educational landscape of the United States.

While the 1785 Ordinance addressed how the land would be divided, the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 tackled the far more complex question of how it would be governed and how new states would be incorporated into the Union. Penned largely by Manasseh Cutler and Rufus King, this document is widely considered one of the most important legislative acts in American history, second only to the Constitution itself. It established a three-stage process for territorial governance: initially, a governor and judges appointed by Congress; then, when the population reached 5,000 free adult males, an elected territorial legislature; and finally, when the population reached 60,000 free inhabitants, the territory could draft a constitution and apply for statehood on equal footing with the original thirteen.

But the Ordinance’s true brilliance lay in its six articles of compact, which outlined a bill of rights for settlers and established fundamental principles. These included freedom of worship, trial by jury, the right to habeas corpus, and protection of property rights. Article III famously declared: "Religion, morality, and knowledge, being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged." This reiterated and expanded upon the commitment to public education established in 1785.

Yet, it was Article VI that etched the Northwest Ordinance into the annals of American history as a truly transformative document: "There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory, otherwise than in the punishment of crimes whereof the party shall have been duly convicted." This bold prohibition, passed by a Congress still grappling with the institution of slavery, drew a distinct line in the sand. It ensured that the vast expanse north of the Ohio River would develop as a region of free labor, setting the stage for the dramatic sectional conflict that would erupt decades later. It was a moral stand, however imperfectly enforced at times, that fundamentally altered the trajectory of American expansion and its eventual struggle over human bondage.

However, this grand vision of ordered expansion and democratic ideals was not without its profound human cost. The land that the ordinances sought to survey and settle was not empty wilderness; it was the ancestral home of numerous Indigenous nations, including the Miami, Shawnee, Delaware, Wyandot, and Potawatomi. For centuries, these peoples had thrived in the rich river valleys and dense forests, cultivating crops, hunting game, and maintaining complex social and political structures. The arrival of American settlers, armed with legislative mandates and a relentless hunger for land, inevitably led to conflict.

The Native American confederacy, led by brilliant strategists like Little Turtle of the Miami and Blue Jacket of the Shawnee, fiercely resisted the encroachment. They inflicted devastating defeats on American forces, most notably St. Clair’s Defeat in 1791, where over 900 American soldiers were killed or wounded – the greatest defeat of the U.S. Army by Native Americans in history. This forced the fledgling United States to commit significant resources to secure the territory. General "Mad Anthony" Wayne was tasked with leading a new, professional army, culminating in the decisive Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. The American victory, though controversial in its tactics, broke the back of the confederacy’s resistance.

The ensuing Treaty of Greenville (1795) forced the cession of vast tracts of land in present-day Ohio and Indiana, opening the floodgates for white settlement. While the treaty acknowledged Native American land rights to remaining areas, it was a hollow promise. The relentless tide of settlers, coupled with subsequent treaties and land cessions, would systematically dispossess Indigenous peoples from their homelands, culminating in the forced removals of the 19th century. The Northwest Ordinance, with its lofty ideals of liberty, ironically contained a clause stating that "the utmost good faith shall always be observed towards the Indians; their lands and property shall never be taken from them without their consent." This promise was, tragically, more often honored in the breach than in the observance.

As the smoke of conflict cleared, settlers poured into the territory. Veterans of the Revolution, land speculators, and ordinary farmers seeking new opportunities flocked to the region. Early towns like Marietta, Ohio, founded in 1788 by the Ohio Company of Associates, became vital hubs. The rugged journey over the Appalachians, often by flatboat down the Ohio River, was fraught with danger, but the promise of fertile land and a fresh start propelled thousands westward. These pioneers faced harsh winters, isolation, disease, and the constant labor of transforming wilderness into farms.

The impact of the slavery prohibition in Article VI cannot be overstated. While not universally absolute – existing slaves were often tacitly allowed, and various forms of indentured servitude and "black laws" attempted to circumvent the spirit of the law – it profoundly shaped the economic and social development of the region. Unlike the cotton-growing South, the Northwest Territory developed a diversified agricultural economy based on free labor, small to medium-sized farms, and burgeoning industrial centers. This fundamental difference would contribute to the widening chasm between North and South, a chasm that would ultimately erupt in the Civil War. The Ohio River became not just a geographical boundary, but a symbolic and actual dividing line between freedom and bondage, a fact that would later make it a crucial artery for the Underground Railroad.

The Old Northwest Territory truly served as a proving ground for American democracy. Its systematic approach to land distribution and governance became the template for all subsequent westward expansion. The principles enshrined in the Northwest Ordinance – the orderly creation of new states, the guarantee of civil liberties, the promotion of public education, and the prohibition of slavery – were replicated in territories stretching to the Pacific. It was here that the concept of an "empire of liberty" was first put into practical, albeit imperfect, application.

In conclusion, the Old Northwest Territory was far more than just a historical footnote; it was a defining chapter in the American story. It demonstrated the power of collective national vision over state particularism, the foresight to plan for orderly growth, and the courage to make a moral stand on the most divisive issue of its time. Its legacy lives on in the rectilinear grid of Midwestern towns and farms, in the commitment to public education that permeates American society, and in the very shape of the nation itself. From the conflicts over land and sovereignty to the ambitious legislative acts that charted its future, the Old Northwest Territory stands as a testament to the challenges and triumphs of a young republic striving to forge its identity and fulfill its promise. It was, indeed, the crucible where much of America’s future was first forged.