The Unspoken Winter of Blood: Unearthing the Truth of the Bear River Massacre

January 29, 1863. A frigid dawn broke over the confluence of the Bear River and Battle Creek in what was then Utah Territory, now southeastern Idaho. The snow lay deep, blanketing the land in a deceptive serenity. But beneath that pristine white, an unspeakable horror unfolded, leaving a stain on American history that would be suppressed, distorted, and largely forgotten for over a century. This was the Bear River Massacre, or as the Northwestern Shoshone people remember it, the Massacre at Boa Ogoi (Great Valley). It was not a battle, but a brutal, one-sided slaughter that claimed the lives of hundreds of innocent men, women, and children, forever altering the destiny of a resilient people.

For decades, official narratives minimized the event, often referring to it as the "Battle of Bear River." However, the truth, preserved through generations of Shoshone oral tradition and later corroborated by historical research, paints a far darker picture. It reveals a deliberate act of extermination, fueled by fear, prejudice, and the relentless march of westward expansion.

A People Under Siege: The Shoshone Way of Life

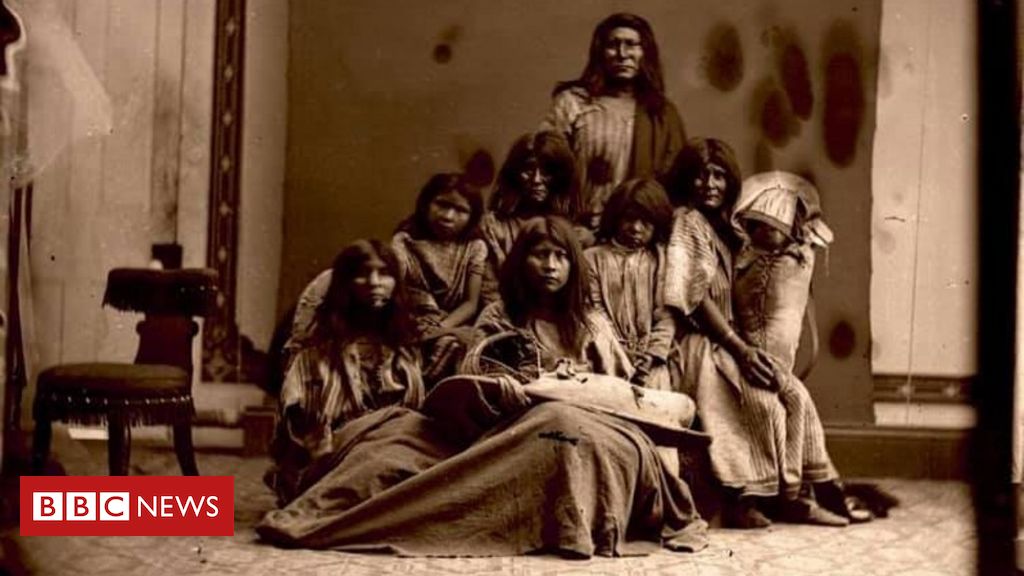

Before the arrival of Euro-American settlers, the Northwestern Shoshone thrived in their ancestral lands, a vast territory encompassing parts of modern-day Utah, Idaho, Wyoming, and Nevada. They were a semi-nomadic people, their lives intricately tied to the rhythms of nature. They fished for salmon and trout in the abundant rivers, hunted deer, elk, and buffalo, and gathered a wide array of roots, berries, and seeds. Their society was structured around family bands, led by respected chiefs, and their culture was rich with spiritual traditions, storytelling, and a deep reverence for the land.

The Bear River valley, specifically the area known as Boa Ogoi, was a particularly vital wintering ground. Its warm springs kept the river from freezing solid, allowing for fishing even in the harshest months, and the surrounding hills offered shelter and game. It was a place of refuge, sustenance, and community, where bands would gather to share resources and celebrate.

However, by the mid-19th century, this way of life was under severe threat. The California Gold Rush of 1849 brought a flood of prospectors and settlers across Shoshone lands. The establishment of the Mormon Trail and later the transcontinental telegraph line further disrupted traditional hunting grounds, polluted water sources, and introduced diseases to which the Shoshone had no immunity. As resources dwindled and their lands were encroached upon, tensions escalated. Livestock belonging to settlers often grazed on native forage, and desperate Shoshone sometimes resorted to taking cattle to survive the harsh winters, leading to accusations of theft and calls for retaliation.

The Catalyst for Carnage: Colonel Connor’s Campaign

The immediate catalyst for the massacre was a series of skirmishes and incidents in the autumn and winter of 1862. Reports, often exaggerated or misattributed, reached the ears of Colonel Patrick Edward Connor, a formidable and ruthless commander of the California Volunteers. Connor’s troops, initially sent to Utah to guard mail routes and protect settlers, viewed the "Indian problem" with a particularly harsh lens. He openly expressed his contempt for Native Americans, advocating for their removal or extermination.

One of the most significant incidents involved an attack on a stagecoach and the alleged killing of two miners. While the perpetrators were never definitively identified as Shoshone from Boa Ogoi, Connor seized upon these events as justification for a punitive expedition. He believed the Shoshone were hostile and dangerous, and he intended to make an example of them.

On January 22, 1863, Connor led approximately 200-300 cavalrymen from Fort Douglas near Salt Lake City. The journey was arduous, marked by deep snow, biting winds, and temperatures plummeting below zero. Several soldiers suffered severe frostbite, a testament to the brutal conditions. Despite the physical toll, Connor pressed on, determined to reach the Shoshone camp at Boa Ogoi, which he had been informed contained a large concentration of people.

The Horror Unfolds: January 29, 1863

As dawn broke on January 29, the soldiers, exhausted and frozen, found the Shoshone camp nestled in a ravine along the Bear River. Approximately 400-500 Northwestern Shoshone, including Chief Sagwitch Timbimboo and other prominent leaders, were encamped there for the winter. They were largely unaware of the impending assault, believing themselves safe in their traditional wintering grounds.

The soldiers initially formed a line, positioning themselves on the bluffs overlooking the camp. What followed was a tactical blunder for the US troops, as the Shoshone, though surprised, managed to utilize the natural defenses of the ravine. They dug rifle pits and returned fire, initially repelling the first wave of attackers and inflicting several casualties on Connor’s men. This brief resistance, however, only intensified Connor’s resolve and his soldiers’ brutality.

Connor, enraged by the resistance, ordered his men to flank the Shoshone. "No prisoners!" he reportedly shouted, an order that effectively sealed the fate of hundreds. The soldiers systematically surrounded the camp, trapping the Shoshone in the ravine. What began as a skirmish quickly devolved into a massacre.

The soldiers, now in a position of overwhelming advantage, poured a relentless barrage of fire into the camp. They targeted not just warriors, but indiscriminately shot at women, children, and the elderly. Survivors recounted scenes of unimaginable horror: mothers shielding their children, only to be cut down by bullets; babies bayoneted in their cradles; the wounded left to freeze or burn. Tipi covers were ripped away, exposing the vulnerable occupants to the bitter cold and the soldiers’ merciless attacks.

Chief Sagwitch Timbimboo, though wounded, managed to escape with a handful of his people, including his young son, Yeager, by plunging into the icy waters of the Bear River. Many who tried to flee across the frozen river were shot or drowned. Those who managed to reach the other side faced the agonizing choice of freezing to death or returning to the carnage.

For hours, the slaughter continued. When the firing finally ceased, the scene was one of utter devastation. The Shoshone camp was a charnel house, littered with the bodies of men, women, and children. Estimates of the dead vary, but most historians now agree that between 250 and 400 Shoshone perished. Among them were nearly all the women and children present, a clear indication that this was not a "battle" but a deliberate act of extermination. In stark contrast, the US forces reported 14 soldiers killed and 49 wounded, a testament to the overwhelming imbalance of the engagement.

The Aftermath and the Suppression of Truth

After the massacre, the soldiers looted the camp, taking horses, furs, and other valuables. They then set fire to the remaining tipis, ensuring that any survivors would face an even more brutal ordeal in the sub-zero temperatures. They left the scene of the atrocity, abandoning the dead to the elements and the few traumatized survivors to their fate.

Colonel Connor, in his official report, painted the event as a glorious victory against a formidable enemy. He described a "severe engagement" and praised his troops for their bravery, completely omitting any mention of the systematic killing of non-combatants. Local newspapers, often echoing Connor’s narrative, celebrated the "victory" and glorified the soldiers, further cementing a false narrative in the public consciousness.

For the Shoshone, the massacre was a catastrophic blow. Entire families were wiped out. The few survivors, like Chief Sagwitch, endured incredible hardships, suffering from frostbite, starvation, and deep psychological trauma. Sagwitch’s son, Yeager, lost his mother and many relatives, a wound that would never fully heal. The massacre decimated the Northwestern Shoshone population, scattering the survivors and fundamentally altering their way of life forever. Many eventually sought refuge with the Mormon community, adopting new ways of life out of sheer necessity for survival.

A Century of Silence: The Long Road to Recognition

For over a century, the true story of the Bear River Massacre remained largely untold outside of Shoshone oral traditions. It was a "forgotten" massacre, overshadowed by other conflicts and deliberately omitted from official histories. The prevailing narrative of westward expansion often glossed over such atrocities, preferring to focus on the triumphs and heroism of settlers and soldiers.

However, the truth, though buried, was not extinguished. Shoshone elders continued to pass down the stories of Boa Ogoi, ensuring that the memory of their ancestors and the horror of that winter day would not be lost. In the latter half of the 20th century, a growing movement among historians, Native American activists, and descendants of the victims began to challenge the official narrative.

Historians like Brigham D. Madsen meticulously researched the event, drawing on Shoshone accounts, military records, and settler diaries, to present a more accurate and comprehensive picture. Their work revealed the extent of the brutality and the deliberate nature of the killings, solidifying the term "massacre" over "battle."

In 1990, the site of the massacre was designated a National Historic Landmark, a crucial step towards national recognition. More recently, in 2021, the name of the nearby stream, previously known as "Battle Creek," was officially changed to "Boa Ogoi," honoring the Shoshone name and reclaiming their history. Today, the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation actively works to preserve the memory of their ancestors, conducting annual ceremonies at the site to honor the victims and educate the public.

Lessons from the Frozen Earth: Remembering Boa Ogoi

The Bear River Massacre stands as a stark reminder of the dark side of American expansion, a chilling example of state-sanctioned violence against indigenous populations. It exposes the brutal realities of Manifest Destiny and the dehumanization that allowed such atrocities to occur. The silence that followed for so long highlights the power of official narratives to shape historical memory and the profound importance of listening to the voices of those who were silenced.

Remembering Boa Ogoi is not about assigning blame in the present, but about acknowledging a difficult and painful past. It is about understanding the enduring trauma inflicted upon the Shoshone people and recognizing their resilience in the face of near annihilation. It is about learning from the mistakes of history, fostering empathy, and striving for a more just and inclusive future.

The wind still whispers through the barren trees along the Bear River, and the snow still falls heavy in winter, but now, the echoes of Boa Ogoi are no longer unspoken. They speak of a profound tragedy, a stolen history, and a resilient spirit that demands to be heard, ensuring that the hundreds of lives lost on that frigid January morning will never again be forgotten.