Of course! Here is a 1,200-word journalistic article about the Hopewell Culture.

Echoes in the Earth: Unearthing the Enduring Mystery of the Hopewell Culture

Beneath the fertile plains of the American Midwest, where cornfields stretch to the horizon and rivers carve ancient paths, lie monumental secrets etched into the very earth. These are the whispers of the Hopewell Culture, an enigmatic pre-Columbian civilization that flourished between 200 BCE and 500 CE. Far from being simple hunter-gatherers, the Hopewell people engineered vast earthworks of astonishing geometric precision, orchestrated continent-spanning trade networks, and produced exquisite works of art that speak of a rich spiritual and social complexity. Yet, for all their achievements, they left behind no written language, no grand cities, and ultimately, vanished from the archaeological record as mysteriously as they appeared, leaving modern scholars to piece together their story from the silent testament of the earth.

To understand the Hopewell is to embark on a journey through time, to a period when North America was a landscape of diverse, evolving societies. The term "Hopewell Culture" itself refers not to a single tribe or unified empire, but rather to a broad, interconnected set of cultural traditions, shared beliefs, and artistic expressions that spread across a vast area, primarily centered in the Ohio River Valley but with influences stretching from the Great Lakes to the Gulf Coast. This widespread influence has led archaeologists to coin the term "Hopewell Interaction Sphere," a testament to their sophisticated network of exchange and communication.

Architects of the Earth: The Monumental Legacy

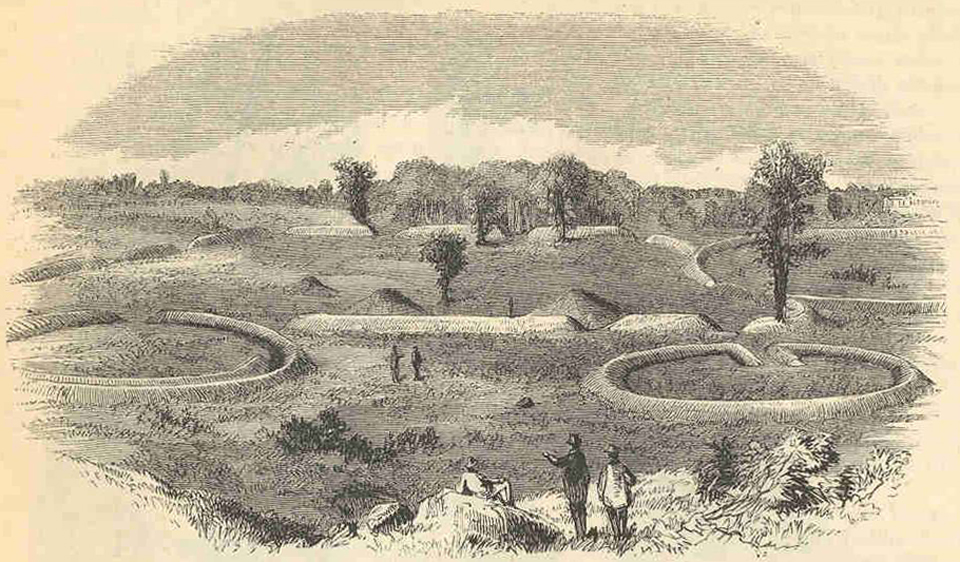

The most striking and enduring legacy of the Hopewell are their monumental earthworks. Imagine vast geometric enclosures – perfect circles, squares, octagons, and intricate combinations thereof – meticulously constructed from tons of earth. These were not defensive fortifications in the traditional sense, but rather sacred ceremonial centers, built with a precision that continues to astound engineers and archaeologists alike.

One of the most breathtaking examples is the Newark Earthworks in Ohio, a UNESCO World Heritage site. Here, an immense circular enclosure connects to a perfectly proportioned octagon, spanning an area larger than the Roman Colosseum. What makes these structures truly remarkable is their apparent alignment with celestial events. The Octagon Earthworks, for instance, are precisely aligned to the extreme northern rise of the moon, a lunar standstill that occurs only once every 18.6 years. This suggests an advanced understanding of astronomy and calendrical cycles, indicating that these sites were not merely places of burial or gathering, but sophisticated observatories and sacred spaces designed to connect the human realm with the cosmos.

"The sheer scale and precision of the Newark Earthworks defy easy explanation," notes Dr. Brad Lepper, an archaeologist and curator for the Ohio History Connection. "They represent an extraordinary investment of labor and knowledge, pointing to a highly organized society capable of coordinating massive communal projects over generations."

Other significant sites include Mound City Group National Historical Park near Chillicothe, Ohio, featuring dozens of burial mounds within a large rectangular enclosure. These mounds often contained elaborate burials of individuals, accompanied by a trove of exotic grave goods, hinting at social hierarchies and a profound belief in an afterlife. The sheer amount of effort involved in moving earth with primitive tools – baskets, digging sticks, and animal hides – speaks volumes about the collective will and spiritual drive of the Hopewell people. It’s estimated that some of these complexes would have required millions of person-hours to construct.

The Hopewell Interaction Sphere: A Web of Exchange

Perhaps one of the most fascinating aspects of the Hopewell Culture was its extensive trade network, the "Hopewell Interaction Sphere." Unlike later societies that might have traded for purely economic gain, the Hopewell exchange appears to have been driven by ritual, status, and the acquisition of exotic, symbolically potent materials. Raw materials traveled hundreds, even thousands, of miles to Hopewell centers:

- Obsidian: From the Rocky Mountains (e.g., Yellowstone National Park)

- Copper: From the Upper Peninsula of Michigan (Lake Superior region)

- Mica: From the Appalachian Mountains (North Carolina, Tennessee)

- Marine Shells: From the Gulf Coast and Atlantic Seaboard

- Galena (lead ore): From the Ozark Mountains

- Alligator teeth and barracuda jaws: From the Gulf Coast

These materials were not simply commodities; they were transformed by Hopewell artisans into objects of breathtaking beauty and spiritual significance. Copper was cold-hammered into intricate effigies of birds, human figures, and geometric shapes, sometimes plated onto wood. Mica was carved into delicate outlines of hands, raptors, and abstract designs. Shells were fashioned into beads and gorgets.

But it is the effigy pipes, often carved from Ohio pipestone (a type of fireclay), that perhaps best exemplify Hopewell artistry. These pipes depict a wide array of animals – birds, bears, wolves, frogs, and human figures – rendered with an astonishing degree of realism and detail. These were not for casual smoking but were likely used in ceremonial contexts, perhaps as a means to connect with the spirit world or to facilitate social bonding during important rituals. The artistic consistency across such a vast geographical area further reinforces the idea of a shared cultural identity and a sophisticated network for the exchange of ideas, not just goods.

"The objects found in Hopewell mounds are not just beautiful artifacts; they are windows into their cosmology," says archaeologist Dr. N’omi Greber. "The choice of materials, the animals depicted, the context of their burial – all speak to a complex spiritual world where nature and ritual were deeply intertwined."

A Glimpse into Daily Life and Society

While the earthworks and exotic artifacts speak of grand ceremonies and distant connections, the everyday life of the Hopewell people was rooted in the fertile lands of the Midwest. They were skilled hunter-gatherers, harvesting wild plants, nuts, and berries, and hunting deer, elk, and various smaller game. They also practiced early forms of agriculture, cultivating local plants like squash, sunflower, gourds, and knotweed. While maize was present, it did not become a dominant food source until much later in the region’s history.

Hopewell settlements were generally small, consisting of scattered hamlets and farmsteads rather than large, concentrated villages. This dispersed settlement pattern suggests that their ceremonial centers, like Newark or Mound City, served as gathering places for people who lived over a wide area, coming together for specific rituals, trade, and social events. Leadership within Hopewell society was likely decentralized, perhaps based on prestige gained through ritual knowledge, trade connections, or skilled craftsmanship, rather than inherited power in a hierarchical state. The presence of elaborate grave goods accompanying certain individuals suggests a system where some members held higher status, possibly acting as spiritual leaders or influential traders.

The emphasis on ritual and ceremony seems to have been a unifying force. The act of building the earthworks, participating in trade expeditions, and sharing in communal feasts and rituals would have fostered a strong sense of collective identity and purpose across the Hopewell Interaction Sphere.

The Enigmatic Decline

Around 400-500 CE, the vibrant Hopewell Culture began to wane. The construction of elaborate earthworks ceased, long-distance trade networks diminished, and the distinctive Hopewell artistic styles faded from the archaeological record. This wasn’t a sudden, cataclysmic collapse or the disappearance of a people, but rather a gradual transformation. The people themselves continued to live in the region, but their cultural practices, social structures, and focus shifted dramatically.

The reasons for this decline remain one of the most enduring mysteries surrounding the Hopewell. Scholars propose several theories, often suggesting a combination of factors:

- Climate Change: A period of colder, drier climate could have strained food resources, leading to increased competition and a need for more localized, pragmatic strategies for survival, thus reducing the energy available for grand ceremonial projects and long-distance trade.

- Social Stress: Internal social tensions, perhaps due to changing leadership dynamics, population pressures, or ideological shifts, could have led to the breakdown of the Interaction Sphere.

- Resource Depletion: Intensive harvesting of certain local resources or overhunting in specific areas might have forced changes in subsistence strategies.

- Shift in Ideology: Perhaps the spiritual beliefs and practices that underpinned the Hopewell way of life lost their resonance, leading people to abandon the elaborate rituals and monumental construction in favor of new forms of social and spiritual expression.

- Rise of Agriculture: As reliance on maize agriculture slowly increased, it may have led to more sedentary, localized communities, diminishing the need for widespread interaction and ceremonial gatherings.

Whatever the precise causes, the Hopewell’s transformation marks a significant turning point in North American prehistory. The societies that emerged in their wake, such as the later Fort Ancient and Mississippian cultures, would adopt different social organizations, often characterized by larger, more permanent villages, increased agricultural dependence, and sometimes more centralized political structures.

An Enduring Legacy

Today, the Hopewell Culture continues to captivate archaeologists, historians, and the public. Their earthworks stand as silent monuments to human ingenuity and spiritual depth, challenging our perceptions of ancient North America. Efforts to preserve these sites, many of which are protected within national historical parks or are candidates for UNESCO World Heritage status, ensure that future generations can marvel at their scale and ponder their meaning.

The Hopewell remind us that history is not a linear progression but a complex tapestry of cultures rising, transforming, and influencing one another. They were not primitive but sophisticated, not isolated but globally connected in their own way, not merely surviving but thriving in a world rich with meaning and purpose. The echoes of their ceremonies still resonate from the ancient mounds, inviting us to listen closely and to continue unraveling the profound mysteries of those who shaped the earth and charted the stars in the heart of North America. Their legacy is a powerful testament to the enduring human spirit, its capacity for wonder, and its profound connection to the land and the cosmos.