Echoes of Empire: Tracing the Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail

Imagine a nation barely a quarter-century old, its western frontier a vast, uncharted canvas. Its president, Thomas Jefferson, a man of Enlightenment ideals and boundless curiosity, dreams of a passage to the Pacific, a scientific survey of new lands, and diplomatic ties with indigenous nations. This audacious vision gave birth to one of America’s most iconic adventures: the Lewis & Clark Expedition. Today, their arduous journey is commemorated by the Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail, a sprawling, 4,900-mile ribbon of history stretching across 16 states, inviting modern-day explorers to step into the footprints of discovery.

The story begins in 1803, with the audacious Louisiana Purchase, an acquisition that doubled the size of the United States overnight, extending its theoretical borders to the distant Rocky Mountains. With the ink barely dry on the treaty, President Jefferson commissioned his private secretary, Meriwether Lewis, to lead an expedition of discovery. Lewis, in turn, chose his former military commander, William Clark, to co-lead. Their mission: to explore the newly acquired territory, find a navigable water route to the Pacific Ocean, document the flora, fauna, and geography, and establish relations with the Native American tribes inhabiting the land.

This was no casual stroll. Assembling a diverse group of soldiers, frontiersmen, and interpreters, famously known as the "Corps of Discovery," Lewis and Clark departed from Camp Dubois (near present-day Hartford, Illinois) in May 1804. Their keelboat and two pirogues pushed against the mighty currents of the Missouri River, a formidable waterway that would be their highway for hundreds of miles. The early days were a brutal introduction to the physical demands of the journey: rowing, poling, and cordelling (pulling the boats from shore) against the relentless river, often battling mosquitoes, heat, and exhaustion.

Their meticulous journals, now invaluable historical treasures, offer a window into their daily lives. Lewis, the scientist, filled pages with detailed observations of plants and animals previously unknown to Western science – from prairie dogs to grizzly bears. Clark, the cartographer, painstakingly mapped the twisting course of the river and the surrounding landscape, correcting centuries of speculation. Their combined efforts laid the foundation for America’s understanding of its interior.

One of the expedition’s most pivotal encounters occurred during their first winter, spent among the Mandan and Hidatsa tribes in present-day North Dakota. Here, they enlisted the services of Toussaint Charbonneau, a French-Canadian fur trader, and his young Shoshone wife, Sacagawea, who was pregnant at the time. Sacagawea, whose name means "Bird Woman," would prove indispensable. Not only did she serve as an interpreter, bridging linguistic and cultural gaps with various tribes, but her very presence – a woman with an infant, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau (affectionately nicknamed "Pomp") – signaled peaceful intentions to wary Native American groups who had never before seen white men. Her knowledge of the land, its edible plants, and the customs of her people, particularly the Shoshone, would later be crucial for navigating the daunting Rocky Mountains.

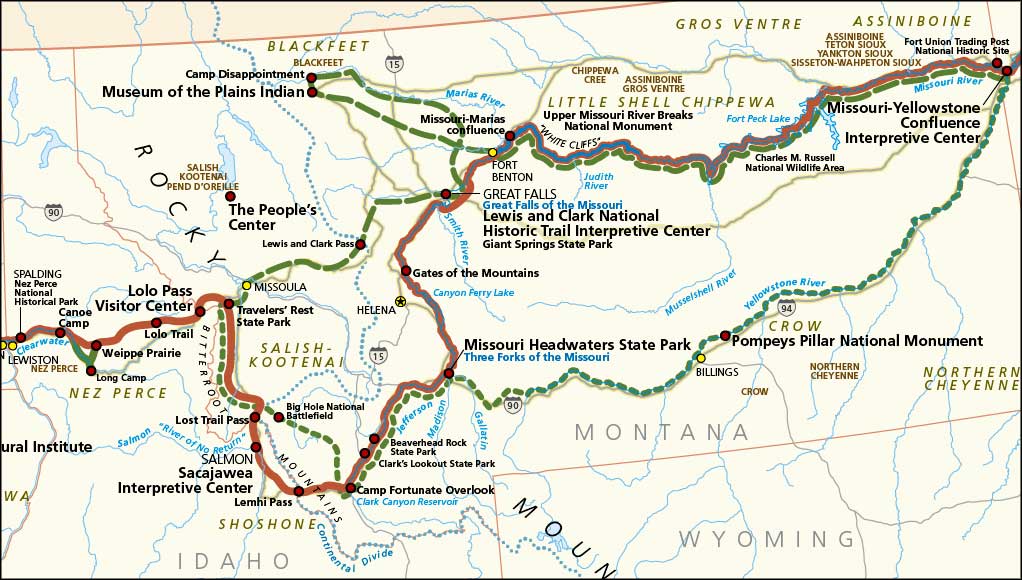

As the Corps ventured further west, the landscape transformed. The vast plains gave way to the towering, snow-capped peaks of the Rockies – the "great impediment" to their water route. The dream of an easy portage between rivers was shattered by the immense, impassable Great Falls of the Missouri in Montana, necessitating an arduous 18-mile overland carry of all their boats and supplies. "The carry of our canoes," Lewis wrote, "was a most laborious task," a testament to the raw grit required. This was a period of near-starvation, exhaustion, and despair, only alleviated by Sacagawea’s remarkable reunion with her long-lost Shoshone tribe, who provided horses and guidance across the formidable Continental Divide.

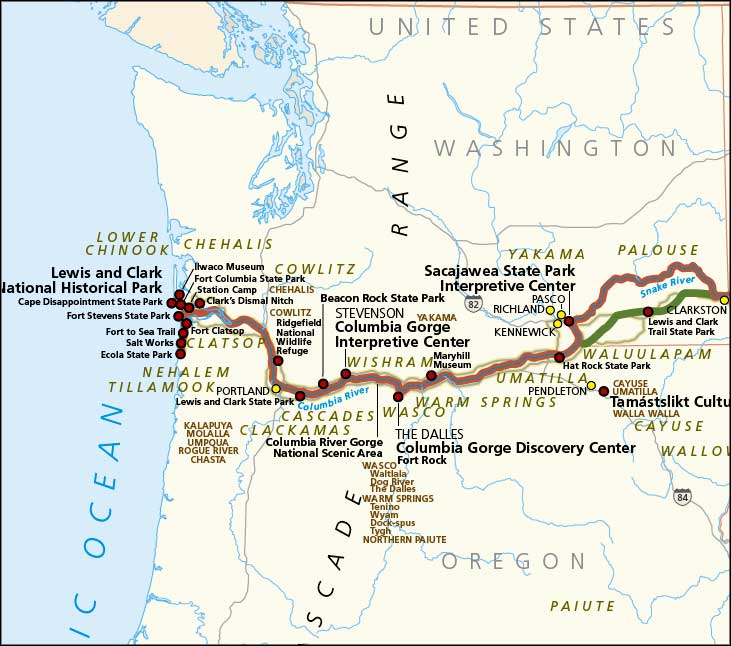

Descending the western slopes, they encountered the Nez Perce, who generously shared their knowledge of the river systems and taught the Corps how to build dugout canoes. These sturdy vessels carried them down the Clearwater, Snake, and finally, the mighty Columbia River, hurtling them towards their ultimate goal. On November 7, 1805, Clark famously scrawled in his journal, "Ocian in view! O! the joy!" after glimpsing the Pacific Ocean through the rain and fog. They spent a wet, miserable winter at Fort Clatsop, near present-day Astoria, Oregon, before beginning their return journey in March 1806.

The return trip was equally challenging but offered new opportunities for exploration. Lewis and Clark split their forces for a time, allowing them to survey more territory and seek alternative routes, before reuniting and retracing their steps back down the Missouri. On September 23, 1806, more than two years after their departure, the Corps of Discovery arrived back in St. Louis, greeted as heroes. They had traveled over 8,000 miles, charted a continent, documented hundreds of new species, and laid the groundwork for westward expansion, albeit at a future cost to the indigenous populations they had encountered.

Today, the Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail isn’t a single, paved path but a vast, interwoven network of sites, parks, and waterways that commemorate and interpret this monumental expedition. Managed by the National Park Service in partnership with numerous state and local agencies, it offers a multi-faceted journey through history, nature, and culture.

For the modern adventurer, the trail offers diverse experiences. You can drive segments of the auto tour routes, marked by distinctive brown signs, stopping at interpretive centers and historical markers that bring the story to life. Sites like the Gateway Arch National Park in St. Louis, the starting point of the journey, or the Fort Clatsop National Memorial in Oregon, their winter encampment, provide immersive historical context. At places like the Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail Interpretive Center in Great Falls, Montana, you can walk through exhibits that recreate the portage, complete with life-sized figures and interactive displays.

But the trail is also about experiencing the landscape as the Corps did. Paddling sections of the Missouri or Columbia Rivers in a canoe or kayak offers a visceral connection to their journey, allowing one to appreciate the sheer physical effort and the breathtaking beauty they witnessed. Hiking trails lead to overlooks that offer panoramic views of the same vistas that awed Lewis and Clark. Birdwatchers can spot species that were new to science when first described by the expedition, while botanists can identify plants cataloged in their journals.

Crucially, the Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail also serves as a vital platform for understanding the complex legacy of the expedition, particularly from Native American perspectives. The story is not just one of heroic discovery, but also one that initiated profound changes, often devastating, for the indigenous peoples who had lived on these lands for millennia. Many interpretive centers now incorporate the voices and histories of the over 50 tribal nations that the Corps encountered, offering a more nuanced and complete narrative. This includes recognizing the often-overlooked contributions of figures like York, Clark’s enslaved servant, whose physical prowess and unique appearance played a significant role in interactions with some Native American groups.

The trail encourages reflection on themes that resonate today: environmental stewardship, cross-cultural understanding, and the enduring human spirit of exploration. It reminds us of the power of meticulous observation and scientific inquiry, and the sheer grit required to overcome seemingly insurmountable obstacles.

As you stand on the banks of the Missouri River, where the Corps of Discovery once pushed off into the unknown, or gaze at the Pacific Ocean from a windswept cliff in Oregon, the echoes of their empire-building journey are palpable. The Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail is more than just a path; it is a living testament to a pivotal moment in American history, a continuous invitation to explore, learn, and connect with the extraordinary adventure that shaped a nation. It beckons us to remember not just where they went, but what they discovered, and what their journey continues to teach us about ourselves and our place in the vast, wild American landscape.