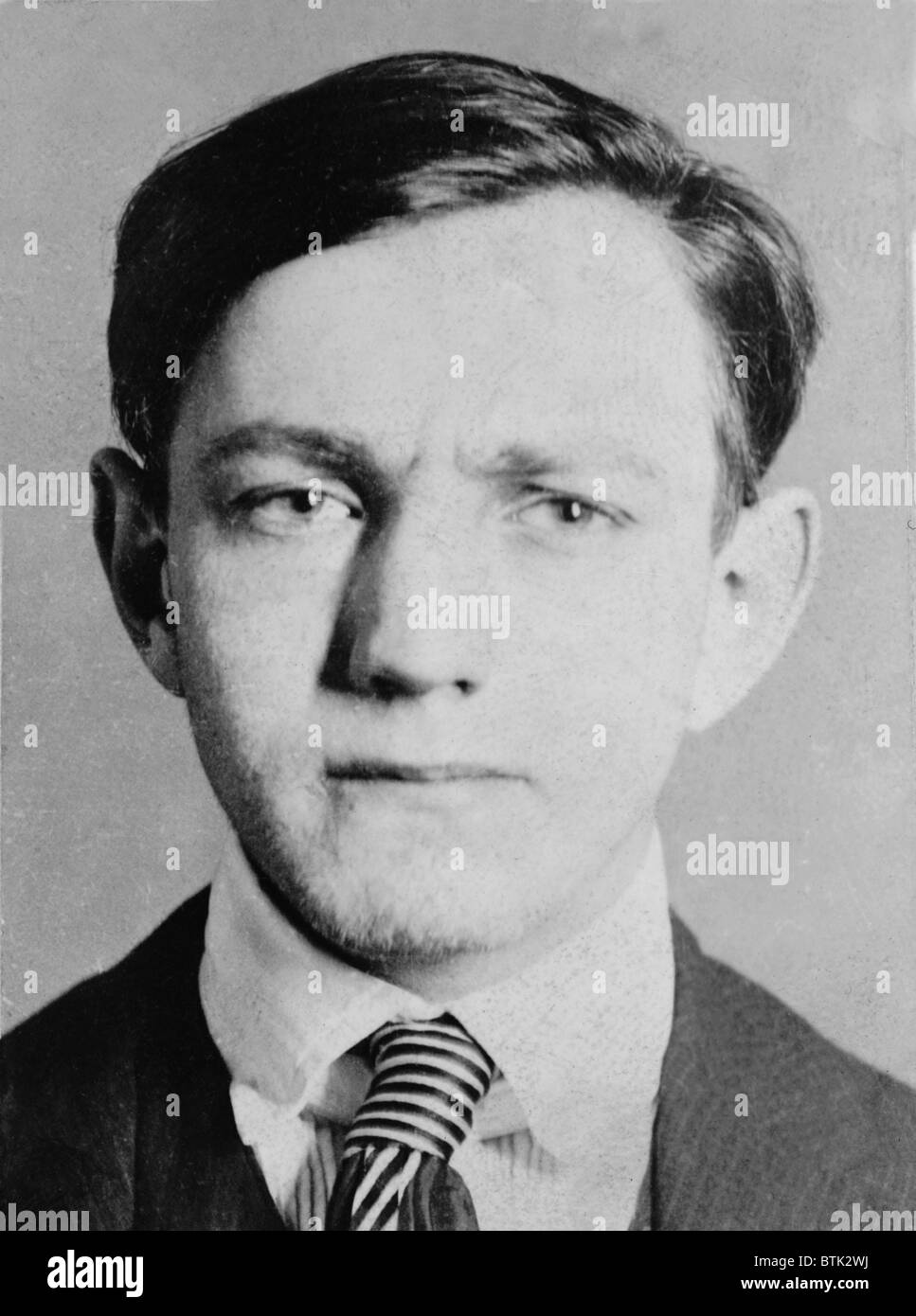

Dutch Schultz: The Bronx Baron, His Violent Reign, and the Delirious Demise of a Gangster King

He was a contradiction in the brutal annals of American organized crime: a ruthless enforcer who could also charm; a meticulous businessman who ultimately succumbed to uncontrolled rage; a legendary gangster whose final moments were a rambling, nonsensical monologue. Arthur Flegenheimer, better known as Dutch Schultz, carved out a formidable empire in Prohibition-era New York, only to see it crumble under the relentless pressure of the law and the cold, calculating hand of his fellow mobsters. His life was a whirlwind of violence and illicit profit, culminating in a spectacular, if pathetic, death that remains one of the most iconic in mob history.

Born in the Bronx in 1902 to German-Jewish immigrant parents, Arthur Flegenheimer’s early life was marked by hardship and a nascent propensity for crime. His father abandoned the family when Arthur was young, leaving his mother to struggle. The streets of the Bronx became his true school, where he quickly learned the currency of intimidation and violence. By his late teens, he was a member of a local gang, known for his ferocity and an almost pathological disregard for authority. The nickname "Dutch Schultz" reportedly came from a notoriously tough local gang member whom Flegenheimer admired and emulated.

Prohibition, enacted in 1920, was not a moral crusade for Schultz; it was a golden opportunity. The ban on alcohol created a black market ripe for exploitation, and Schultz, with his crew, plunged headfirst into bootlegging. He started small, hijacking rival beer trucks and muscling into speakeasies. But Schultz was no mere street thug; he possessed a sharp, albeit twisted, business acumen. He understood logistics, supply chains, and the importance of controlling territory. Soon, he had established a sophisticated network of breweries, distribution routes, and speakeasies, primarily dominating the Bronx and Upper Manhattan. His beer, often watered down and sold at exorbitant prices, flowed freely through a thirsty city.

Schultz’s empire wasn’t built on beer alone. He quickly diversified, recognizing the immense, untapped potential of the "numbers racket" or policy game. This illegal lottery, popular in working-class neighborhoods, involved betting small sums on the last digits of the daily stock market figures. It was a cash cow, generating millions in untaxed revenue. Schultz streamlined the operation, employing an army of "collectors" and "runners" and establishing a complex accounting system overseen by his brilliant, if understated, financial wizard, Otto "Abbadabba" Berman. Berman, a diminutive math savant, could reportedly calculate complex odds and profits in his head.

However, business acumen was always secondary to his preferred method of problem-solving: extreme violence. Schultz was notoriously short-tempered and ruthless. Rivals who encroached on his territory or defaulted on payments faced brutal retribution. The most famous of his early feuds was with the notorious Irish gangster Legs Diamond, a flamboyant bootlegger who operated primarily in Hell’s Kitchen and upstate New York. Their rivalry was marked by a series of bloody shootouts and assassination attempts that left numerous bodies in their wake. Diamond, known for his uncanny ability to survive multiple attempts on his life, famously quipped after one shooting, "I must have a charmed life." Schultz, however, was determined to end that charm. While never definitively proven, it is widely believed that Schultz’s men were responsible for Diamond’s eventual demise in December 1931, found dead in his Albany apartment. With Diamond out of the way, Schultz consolidated his power further, becoming one of New York’s undisputed "Beer Barons."

As the 1930s dawned, Schultz’s power was immense, but so was the scrutiny. The repeal of Prohibition in 1933 meant his beer empire was drying up, forcing him to rely even more heavily on the numbers racket and other illicit activities, such as control over restaurant and laundry unions. More significantly, a formidable new enemy emerged: Thomas E. Dewey, a relentless and ambitious special prosecutor. Dewey, dubbed the "Gangbuster," made it his mission to dismantle organized crime in New York, and Dutch Schultz was at the top of his hit list.

Dewey, recognizing the difficulty of securing convictions for murder or bootlegging, pursued Schultz on tax evasion charges—a strategy famously employed against Al Capone. In 1934, Schultz was indicted on federal income tax evasion. The ensuing legal battle was a testament to Schultz’s influence and cunning. The first trial in Syracuse ended in a hung jury. For the second trial, moved to the small, remote town of Malone in upstate New York, Schultz employed a charm offensive rarely seen from such a brutal man. He mingled with the locals, bought them drinks, donated to charities, and even bought a plot in the local cemetery, all while his lieutenants engaged in jury tampering. Astonishingly, he was acquitted in August 1935.

The acquittal, however, was a Pyrrhic victory. Schultz was free, but the federal government still wanted him, and Dewey remained a persistent threat. Furthermore, the relentless pressure had taken a toll on Schultz. He grew increasingly paranoid, suspecting betrayal everywhere. His temper, always volatile, became even more erratic and dangerous. He began to believe that Dewey was not just an adversary but a personal nemesis, and he became obsessed with the idea of having the prosecutor killed.

This obsession proved to be his undoing. Schultz proposed to "The Commission," the newly formed governing body of the American Mafia (which included powerful figures like Lucky Luciano, Meyer Lansky, Frank Costello, and Joe Adonis), that Dewey be assassinated. The Commission, eager to avoid the kind of public outrage and federal crackdown that such a high-profile hit would inevitably cause, flatly rejected the idea. They recognized that killing a prosecutor would cross an unwritten line, inviting unprecedented heat on all organized crime.

Schultz, however, was not to be reasoned with. He reportedly declared that he would proceed with the hit on Dewey regardless of the Commission’s decision. This act of defiance, combined with his increasingly erratic behavior and the constant attention he was drawing from law enforcement, sealed his fate. The Commission, valuing stability and long-term profit over individual vendettas, issued a counter-order: Dutch Schultz had to be eliminated.

On the evening of October 23, 1935, Schultz and four of his lieutenants—Otto Berman, Lulu Rosenkrantz, and Abe Landau—were at the Palace Chophouse restaurant in Newark, New Jersey, a neutral territory chosen for a meeting. The hit squad, allegedly comprised of Mendy Weiss and Charles Workman (under the command of Louis "Lepke" Buchalter and Albert Anastasia of Murder Inc.), burst in. Schultz was in the men’s room when the gunmen arrived. Workman shot him first, hitting him in the abdomen and bladder. Weiss then moved to the table, riddling Berman, Rosenkrantz, and Landau with bullets. Berman died almost instantly, Rosenkrantz and Landau hours later.

Schultz, despite being mortally wounded, staggered out of the bathroom and collapsed, still conscious. He was rushed to Newark City Hospital, where he lingered for approximately 22 hours. In his final hours, under the influence of pain and delirium, he drifted in and out of consciousness, muttering a stream of fragmented, nonsensical phrases. A police stenographer, Frank F. Forbes, meticulously recorded every word, creating one of the most bizarre and famous deathbed confessions in history.

Schultz’s "last words" are a chaotic mosaic of business dealings, childhood memories, fear, and frustration. "A boy has never wept… honest, I am a good guy," he mumbled at one point. He spoke of "French-Canadian bean soup," of wanting to "pay the bill," and repeatedly called out "Mama." He referenced figures from his past, his fear of being caught, and his belief that he was still in control. "You can’t do that to me… I’m a good guy," he insisted. "Please, please, Mama." The transcript reads like a stream-of-consciousness poem, offering a haunting, if incoherent, glimpse into the mind of a dying gangster. It was a pitiful, undignified end for a man who had commanded so much fear and power.

Dutch Schultz’s death marked the end of an era. With Prohibition long over, the wild, individualistic gangsters who had thrived on its chaos were being replaced by a more organized, corporate structure. The Commission’s decision to sanction Schultz’s murder solidified its authority and established a precedent: no one, not even a powerful gang boss, was above the rules. His demise was a stark warning to those who would defy the nascent "National Crime Syndicate."

Today, Dutch Schultz is remembered not just for his ruthless ambition and violent reign but for the strange, almost theatrical, final act of his life. The transcript of his delirious ramblings continues to fascinate historians and true crime enthusiasts, a poignant and perplexing epitaph for the Bronx Baron who thought he was untouchable, only to discover that even the most feared gangster could be silenced, his final words reduced to a jumble of incoherent fear and regret. He was a product of his time, a testament to the opportunities and dangers of the Roaring Twenties and the Great Depression, a figure whose life and death helped shape the very landscape of American organized crime.