From Rebellion to Republic: Charting America’s Formative Decades

The birth of a nation is rarely a seamless affair, and for the United States, its formative years were a crucible of idealism, conflict, and unprecedented experimentation. From the defiant cries for independence to the establishment of a robust, albeit imperfect, federal system, the American timeline of its "new nation" phase is a saga of audacious visionaries grappling with the messy realities of self-governance, westward expansion, and the enduring challenge of defining what it truly meant to be American.

The Spark of Revolution: A Nation Forged in Defiance (1760s – 1776)

The seeds of American independence were sown not in a single moment, but in decades of simmering resentment against British imperial policies. Following the costly Seven Years’ War (known in America as the French and Indian War), Britain sought to replenish its coffers by levying new taxes on its American colonies. Acts like the Stamp Act (1765), the Townshend Acts (1767), and the Tea Act (1773) ignited a fierce debate over "no taxation without representation," challenging the very premise of parliamentary authority over distant colonies.

Intellectual currents of the Enlightenment, particularly the writings of John Locke on natural rights and the social contract, provided a philosophical bedrock for colonial grievances. Figures like Samuel Adams and Patrick Henry galvanized public opinion, leading to protests, boycotts, and ultimately, armed confrontations such as the Boston Massacre (1770) and the Boston Tea Party (1773).

The escalating tensions culminated in the First Continental Congress in 1774, where colonial delegates debated their response to British oppression. Yet, it was the skirmishes at Lexington and Concord in April 1775 that marked the true outbreak of armed conflict. The publication of Thomas Paine’s "Common Sense" in January 1776 proved to be a watershed moment. This powerful pamphlet, written in accessible language, passionately argued for complete independence, dismissing monarchy as an absurdity and laying out a compelling case for a republican form of government. Paine’s words resonated deeply, pushing public opinion decisively towards separation.

Just months later, on July 4, 1776, the Second Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence, a document primarily drafted by Thomas Jefferson. It was not merely a declaration of war but a philosophical statement, asserting the inherent rights of "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" and the right of the people to alter or abolish a destructive government. This audacious pronouncement, declaring thirteen disparate colonies "free and independent States," marked the official birth of the American nation, albeit one still fighting for its very existence.

The Crucible of War and the Perils of Confederation (1775 – 1787)

The Revolutionary War was a long and arduous struggle against the mightiest military power of the era. Led by General George Washington, the Continental Army faced immense challenges: chronic shortages, lack of training, and the constant threat of desertion. Key victories at Saratoga (1777), which secured the crucial alliance with France, and Yorktown (1781), where a combined American and French force trapped Cornwallis’s army, proved decisive. The Treaty of Paris, signed in 1783, officially recognized American independence and established its vast territorial boundaries.

However, winning the war was one thing; building a stable nation was another. The nascent United States operated under the Articles of Confederation, adopted in 1781. This document reflected the profound distrust of strong central authority prevalent after the experience with British monarchy. It created a loose "league of friendship" among the states, with a weak central government that lacked the power to tax, regulate interstate commerce, or enforce laws effectively.

The consequences were dire. States quarreled over borders and trade, a national debt mounted unpaid, and economic chaos threatened to unravel the fragile union. Shay’s Rebellion (1786-1787), an uprising of indebted farmers in Massachusetts, starkly exposed the impotence of the national government and served as a powerful catalyst for change. As George Washington famously remarked, the nation was "on the verge of anarchy."

Crafting a More Perfect Union: The Constitutional Moment (1787 – 1791)

The urgent need for a stronger federal government led to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787. Fifty-five delegates, including intellectual giants like James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and Benjamin Franklin, gathered in secrecy to revise the Articles. What emerged, however, was an entirely new framework: the United States Constitution.

This document represented a series of ingenious compromises. The Great Compromise (or Connecticut Compromise) resolved the debate between large and small states over representation by creating a bicameral legislature: the House of Representatives (based on population) and the Senate (equal representation for each state). The Three-fifths Compromise addressed the contentious issue of slavery by counting enslaved individuals as three-fifths of a person for both representation and taxation. Perhaps most crucially, it established a system of checks and balances and separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, designed to prevent any single branch from becoming too powerful.

The Constitution’s ratification was not a foregone conclusion. Fierce debates erupted between Federalists, who supported the stronger central government, and Anti-Federalists, who feared it would infringe on individual liberties and states’ rights. The Federalist Papers, a series of 85 essays written by James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay, eloquently argued for the Constitution’s adoption, explaining its principles and defending its structure. In Federalist No. 51, Madison famously articulated the necessity of government control: "If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary."

To assuage Anti-Federalist concerns, Federalists promised to add a Bill of Rights. Once ratified in 1788, the first ten amendments, known as the Bill of Rights, were added in 1791, guaranteeing fundamental freedoms such as speech, religion, and assembly, and protecting against government overreach. This final act solidified the framework for the American Republic.

Launching the Republic: Washington’s Precedent-Setting Years (1789 – 1797)

With the Constitution ratified, the nation faced the daunting task of establishing its new government. George Washington, the revered hero of the Revolution, was unanimously elected as the first President in 1789. His two terms were critical in setting precedents for the executive branch and establishing the authority of the federal government.

Washington assembled a formidable cabinet, including Thomas Jefferson as Secretary of State and Alexander Hamilton as Secretary of the Treasury. These two men, however, represented fundamentally different visions for the nation’s future, leading to the formation of America’s first political parties: Hamilton’s Federalists (advocating for a strong central government, manufacturing, and a national bank) and Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans (favoring states’ rights, an agrarian economy, and limited federal power).

Hamilton’s financial plan, which included assuming state debts, creating a national bank, and imposing tariffs, was instrumental in stabilizing the nation’s economy but also sparked intense political division. Washington’s handling of the Whiskey Rebellion (1794), a protest by Pennsylvania farmers against an excise tax on whiskey, demonstrated the federal government’s new authority to enforce laws and suppress domestic insurrections—a stark contrast to the impotence of the Articles of Confederation.

In foreign policy, Washington steered a neutral course, navigating the complex Anglo-French conflicts of the era. His Farewell Address (1796) offered prescient advice, warning against the dangers of political factions and entangling foreign alliances—a doctrine that would influence American foreign policy for generations.

Defining the Nation’s Character: Expansion and Identity (1797 – 1823)

The early 19th century saw the young nation grapple with its identity and expand its horizons. The "Revolution of 1800," where Thomas Jefferson, a Democratic-Republican, peacefully succeeded Federalist John Adams, marked the first peaceful transfer of power between opposing political parties—a monumental achievement for a new republic.

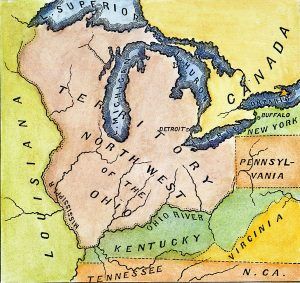

Jefferson’s presidency is best remembered for the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. For a mere $15 million, the United States acquired 828,000 square miles from France, effectively doubling the nation’s size and opening vast new territories for westward expansion. This monumental land deal, though raising constitutional questions for Jefferson, cemented the vision of an agrarian republic stretching across the continent. The subsequent Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804-1806) explored these new lands, paving the way for future settlement.

The nation’s sovereignty was once again tested in the War of 1812 against Great Britain. Causes included British impressment of American sailors, interference with American trade, and support for Native American resistance. Though militarily inconclusive, the war fostered a strong sense of national unity and solidified America’s independence. The burning of Washington D.C. by British troops and Andrew Jackson’s decisive victory at the Battle of New Orleans (fought after the peace treaty was signed but before news reached America) became powerful symbols of American resilience. The war also inspired Francis Scott Key to write "The Star-Spangled Banner."

Following the War of 1812, the nation entered an "Era of Good Feelings," marked by relative political harmony and a surge of nationalism under President James Monroe. This period culminated in the Monroe Doctrine (1823), a landmark foreign policy statement declaring that European powers should no longer colonize or interfere with independent states in the Americas. This bold declaration signaled America’s growing confidence and its intention to assert its influence in the Western Hemisphere.

A Nation in Motion: Westward Expansion and Internal Strife (1820s – 1850s)

The spirit of westward expansion became a defining characteristic of the new nation. Fueled by the concept of Manifest Destiny—the belief that America was divinely ordained to expand across the North American continent—settlers poured into new territories. The construction of canals (like the Erie Canal in 1825) and later railroads facilitated this movement, connecting nascent industries in the East with agricultural lands in the West.

The presidency of Andrew Jackson (1829-1837) ushered in an era of "Jacksonian Democracy," characterized by expanded suffrage for white men, a more populist political style, and a strengthening of the executive branch. However, this era also saw the dark chapter of the Indian Removal Act (1830) and the forced relocation of Native American tribes, most infamously the Cherokee on the "Trail of Tears," highlighting the often brutal cost of westward expansion.

Territorial ambitions led to the annexation of Texas in 1845 and the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), which resulted in the United States acquiring vast territories including California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, and parts of New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming. With this acquisition, the nation truly stretched from "sea to shining sea."

Yet, with every new territory, the fundamental contradiction at the heart of the American experiment—slavery—grew more volatile. The question of whether new states would enter the Union as "free" or "slave" states fueled intense sectional tensions, leading to political compromises like the Missouri Compromise (1820) and the Compromise of 1850. These temporary fixes only papered over the deep divisions, pushing the nation inexorably towards its greatest crisis.

Conclusion: An Ever-Evolving Experiment

The timeline of America’s new nation phase, spanning from the revolutionary fervor of the 1770s to the brink of civil war in the 1850s, is a testament to the immense challenges and profound achievements of a people striving to build a self-governing republic. It was a period marked by audacious declarations of liberty, the crafting of an enduring constitutional framework, the establishment of critical democratic precedents, and an unprecedented expansion across a vast continent.

The journey was far from perfect, marred by the brutal realities of slavery and the displacement of Native Americans. Yet, the foundational principles laid down by the revolutionaries and enshrined in the Constitution — popular sovereignty, individual rights, and the pursuit of a "more perfect Union" — provided the bedrock for a nation that would continue to evolve, challenge its own ideals, and ultimately redefine its promise for generations to come. The "new nation" of America, in its initial tumultuous decades, forged an identity that, for better or worse, continues to shape its destiny.