The Unfolding Tapestry: A Journalistic Look at the Colonization of America

Before the sails of European ships pierced the horizon, what we now call "America" was a vibrant, diverse continent, home to millions of Indigenous peoples. For millennia, sophisticated civilizations flourished, from the sprawling urban centers of the Mississippian culture to the intricate agricultural societies of the Iroquois, the advanced astronomical knowledge of the Maya, and the vast empires of the Inca and Aztec. These were not empty lands, nor were their inhabitants primitives awaiting discovery. They were complex societies with rich histories, unique spiritual beliefs, sophisticated governance, and thriving trade networks.

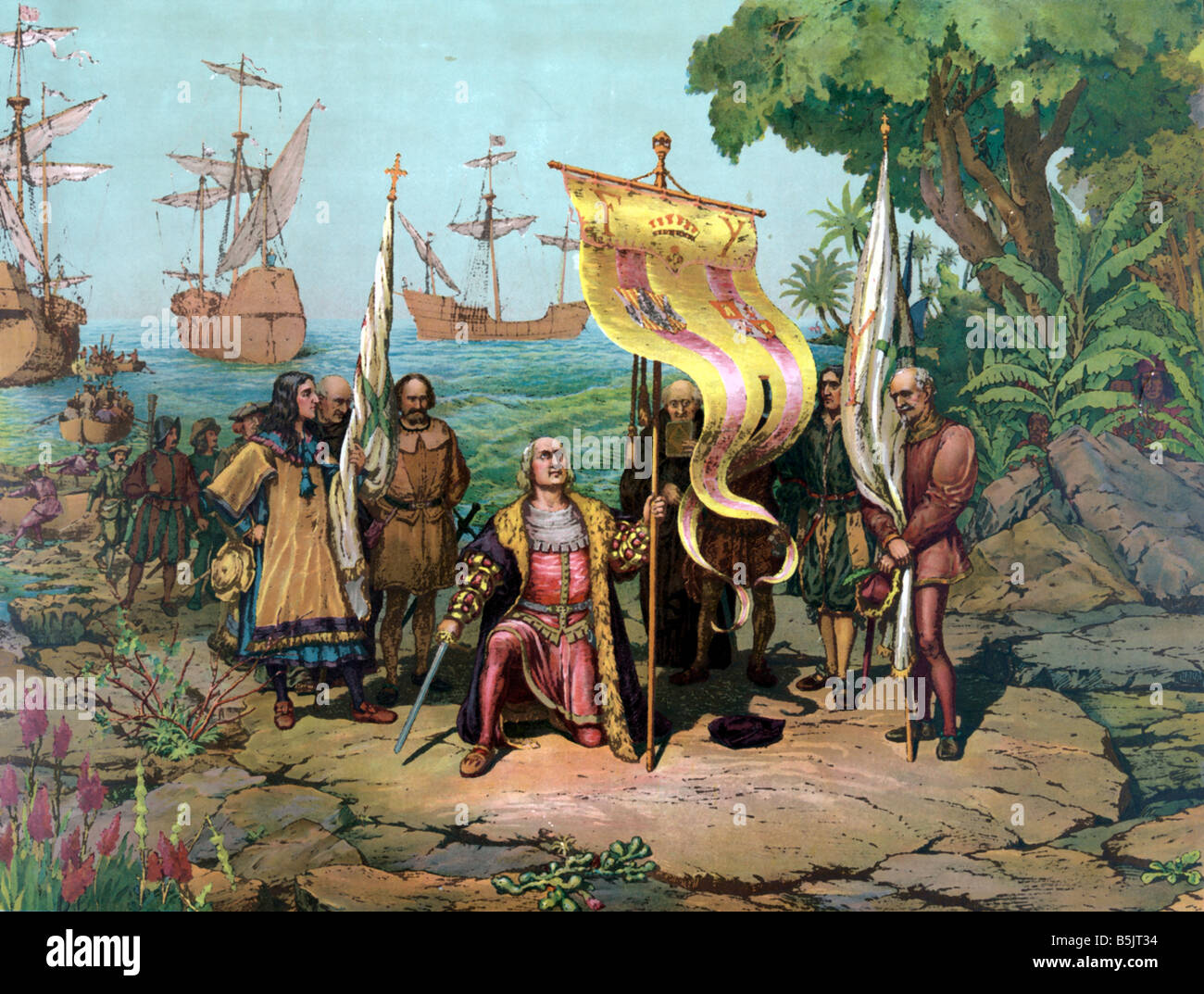

Then came 1492. Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the Caribbean, though often romanticized as the "discovery" of the New World, marked not a beginning, but a violent collision of worlds, irrevocably altering the course of human history. This encounter ignited a multi-century process of colonization, driven by a potent mix of economic ambition, religious fervor, geopolitical rivalry, and an insatiable hunger for land and resources. It was a period that shaped modern nations, created unprecedented wealth, and simultaneously wrought unimaginable destruction upon the continent’s original inhabitants.

The Spanish Spearhead: Gold, God, and Glory

The Spanish were the first to aggressively stake their claim. Driven by the "three G’s"—Gold, God, and Glory—conquistadors like Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro led expeditions that would become infamous for their brutality and effectiveness. Cortés, with a small force of Spanish soldiers, exploited internal divisions within the Aztec Empire, conquering its capital Tenochtitlan (modern-day Mexico City) by 1521. Pizarro replicated this feat in the Andes, toppling the vast Inca Empire in the 1530s.

The allure of precious metals was immense. The mines of Potosí in Bolivia, for instance, yielded such vast quantities of silver that they transformed the European economy and funded the Spanish Empire for centuries. This wealth, however, came at an astronomical human cost. Indigenous populations were forced into brutal labor systems like the encomienda, a de facto slavery that granted Spanish settlers control over Native labor and land in exchange for "protection" and religious instruction.

Beyond the sword, disease proved to be the deadliest weapon. Lacking immunity to European pathogens like smallpox, measles, and influenza, Indigenous populations experienced a demographic catastrophe. Historians estimate that up to 90% of the Native population perished in the century following European contact. As Bartolomé de las Casas, a Dominican friar who became a vocal critic of Spanish cruelty, observed in his A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies (1552), the Spanish "have been so cruel, so merciless, so brutal, so utterly without pity…that they have done everything they could to exterminate these people from the face of the earth." His powerful, albeit disturbing, accounts paint a vivid picture of the horrors inflicted.

France and England: Different Approaches, Similar Ends

While Spain carved out a vast empire in Central and South America, other European powers soon joined the scramble. France focused its efforts further north, establishing New France in present-day Canada and the Mississippi River Valley. Unlike the Spanish, French colonization was less about large-scale settlement and mineral extraction and more about the lucrative fur trade. French coureurs des bois (runners of the woods) forged alliances with various Indigenous nations, learning their languages and customs, and often intermarrying. This more cooperative, albeit still exploitative, relationship was driven by economic necessity: successful fur trading required Indigenous knowledge and labor. Key settlements included Quebec (1608) and later New Orleans (1718).

England, a latecomer to the colonial game, pursued a different, more permanent vision. Their motivations were a complex tapestry of economic opportunity, religious freedom, and geopolitical rivalry with Spain. The first permanent English settlement was Jamestown, Virginia, established in 1607 by the Virginia Company, a joint-stock company seeking profit. The early years were fraught with hardship, starvation, and conflict with the powerful Powhatan Confederacy. The colony only found its footing with the cultivation of tobacco, a highly addictive cash crop that fueled demand for land and labor. "Tobacco," as one early colonist noted, "made us forget our miseries."

Further north, religious dissenters sought refuge. In 1620, the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth, Massachusetts, seeking to practice their faith freely. A decade later, a much larger wave of Puritans, led by John Winthrop, founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony, aiming to create a "city upon a hill"—a moral exemplar for the world. Winthrop’s sermon "A Model of Christian Charity" articulated this vision: "For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill. The eyes of all people are upon us." While these colonies offered religious freedom for their own members, they often proved intolerant of other faiths and deeply hostile towards Indigenous peoples whose lands they coveted.

The Relentless March of Expansion and the Shadow of Slavery

As English colonies expanded, so did the pressure on Indigenous lands. Treaties were often broken, and conflicts erupted frequently. King Philip’s War (1675-1678) in New England, a brutal and devastating conflict between English colonists and a confederation of Native tribes led by Metacom (known to the English as King Philip), exemplified the existential struggle for survival. The war resulted in massive casualties on both sides and effectively ended significant Indigenous resistance in southern New England. The relentless European demand for land, driven by agricultural expansion and increasing immigration, meant that Indigenous peoples were systematically dispossessed, pushed westward, or confined to ever-shrinking reservations.

A darker, equally devastating chapter in the colonization story was the transatlantic slave trade. As the demand for labor in the rapidly expanding agricultural economies of the Southern colonies (particularly for tobacco, rice, and indigo) outstripped the supply of indentured servants, Europeans turned to enslaved Africans. From the early 17th century until the mid-19th century, millions of Africans were forcibly transported across the Atlantic in horrific conditions, enduring unimaginable suffering and brutality. Stripped of their freedom, culture, and humanity, they were subjected to chattel slavery, a system designed to exploit their labor for generations. This forced migration and enslavement laid the foundations for systemic racism and economic inequality that continue to plague societies in the Americas today.

A Legacy of Contradictions

By the mid-18th century, a mosaic of European colonies stretched across the Americas: Spanish viceroyalties in the south and southwest, French territories in the interior, and a burgeoning string of British colonies along the Atlantic seaboard. These colonies were governed under the economic theory of mercantilism, where colonies existed to enrich the mother country by providing raw materials and serving as markets for manufactured goods. This system fostered competition and ultimately led to conflicts like the French and Indian War (Seven Years’ War), which reshaped the colonial landscape.

The colonization of America is a story fraught with contradictions. It brought new technologies, languages, and ideas, laying the groundwork for modern nations and global trade. Yet, it also unleashed unparalleled destruction, cultural annihilation, and human suffering. The "discovery" of the Americas was, for its Indigenous inhabitants, an invasion that initiated centuries of trauma, displacement, and genocide. The quest for freedom by some European settlers directly led to the enslavement of millions of Africans.

Understanding this complex history requires confronting uncomfortable truths. It demands acknowledging the immense contributions and resilience of Indigenous peoples, who continue to fight for their rights, cultures, and sovereignty. It means recognizing the profound and lasting impact of slavery on the social, economic, and political fabric of the Americas. The tapestry of American history is woven with threads of ambition and innovation, but also with threads of conquest, exploitation, and profound injustice. To truly comprehend the present, one must bravely and critically examine the full, multifaceted legacy of its colonial past.