Doniphan’s Odyssey: The Citizen Soldiers Who Conquered a Desert Empire

The annals of military history are replete with tales of grand campaigns and strategic masterstrokes, often executed by professional armies honed by years of discipline and training. Yet, sometimes, an expedition emerges from the dust and chaos of conflict that defies conventional wisdom, a saga of amateur soldiers achieving feats that would humble seasoned veterans. Such is the story of Doniphan’s Expedition, an extraordinary odyssey during the Mexican-American War that saw a ragged band of Missouri volunteers march thousands of miles through unforgiving terrain, conquer a vast enemy territory, and return home as unsung heroes, their names etched into the fabric of American expansion.

In the spring of 1846, the United States, fueled by the fervent ideology of Manifest Destiny, declared war on Mexico. President James K. Polk’s ambitions stretched far beyond the disputed Texas border; he envisioned an American dominion reaching the Pacific, encompassing the vast, sparsely populated territories of New Mexico and California. To achieve this, Brigadier General Stephen W. Kearny was tasked with forming the "Army of the West," a force largely composed of volunteers from the burgeoning frontier state of Missouri. Among these was the First Regiment of Missouri Mounted Volunteers, commanded by a remarkable figure: Colonel Alexander William Doniphan.

Doniphan, a lawyer by trade and a former state legislator, was hardly a career military man. His soldiers, too, were a motley crew: farmers, frontiersmen, merchants, and adventurers, united by a fierce independent spirit and a yearning for opportunity. They were men accustomed to hard living and the rigors of the frontier, but utterly devoid of formal military training beyond their brief enlistment. Yet, it was these "citizen soldiers," as they would come to be known, who would embark on one of the most remarkable and arduous campaigns in American military history.

The initial objective was Santa Fe, the capital of New Mexico. In June 1846, Kearny’s Army of the West, with Doniphan’s regiment forming a crucial part, set out from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. The march across the arid plains of the Santa Fe Trail was an immediate test of endurance. Water was scarce, provisions often ran low, and the scorching sun beat down relentlessly. Despite the hardships, the American force reached Santa Fe in August without firing a shot, Kearny successfully negotiating the surrender of the city and declaring New Mexico a U.S. territory.

It was here that Doniphan’s independent saga truly began. General Kearny, after establishing a provisional government in Santa Fe, pressed on towards California with a smaller, select force. He left Doniphan with a new, ambitious, and seemingly impossible order: to maintain order in New Mexico, then march south through the vast, hostile Chihuahua Desert, secure the Mexican state of Chihuahua, and ultimately link up with General Zachary Taylor’s forces in northern Mexico. This was an assignment of staggering proportions, demanding an independent march of hundreds of miles into enemy territory, with an ill-supplied, largely untrained volunteer force.

Doniphan’s men initially faced the daunting task of suppressing a nascent rebellion in New Mexico. Their presence, however, was enough to deter a full-scale uprising, showcasing the quiet authority and determination of their leader. With New Mexico pacified for the time being, Doniphan turned his attention to Chihuahua, a state considered a major stronghold of Mexican power and a key strategic prize.

On December 14, 1846, Doniphan’s roughly 850 men, augmented by a small artillery battery, began their march south from El Paso del Norte (modern-day Ciudad Juárez). The journey was brutal. The Chihuahua Desert stretched before them, an unforgiving landscape of endless sand, scrub brush, and towering mountains. Water sources were few and far between, often saline or tainted. Supplies were perpetually scarce, forcing the men to forage for food and rely on their wits. They faced not only the elements but also the constant threat of attack from Apache and Comanche raiders, who saw the slow-moving column as an easy target.

Despite these immense challenges, Doniphan’s unique leadership style kept his men unified and determined. He was not a distant, imperious commander but a pragmatic leader who understood the nature of his citizen soldiers. He allowed for a degree of democratic decision-making and encouraged resourcefulness, earning the respect and loyalty of his men. As one contemporary observer noted, Doniphan "never used his rank, or assumed the dictatorial tone, but counselled with his officers, and invited the opinions of his men." This approach, unconventional for the era, was perfectly suited to his independent-minded volunteers.

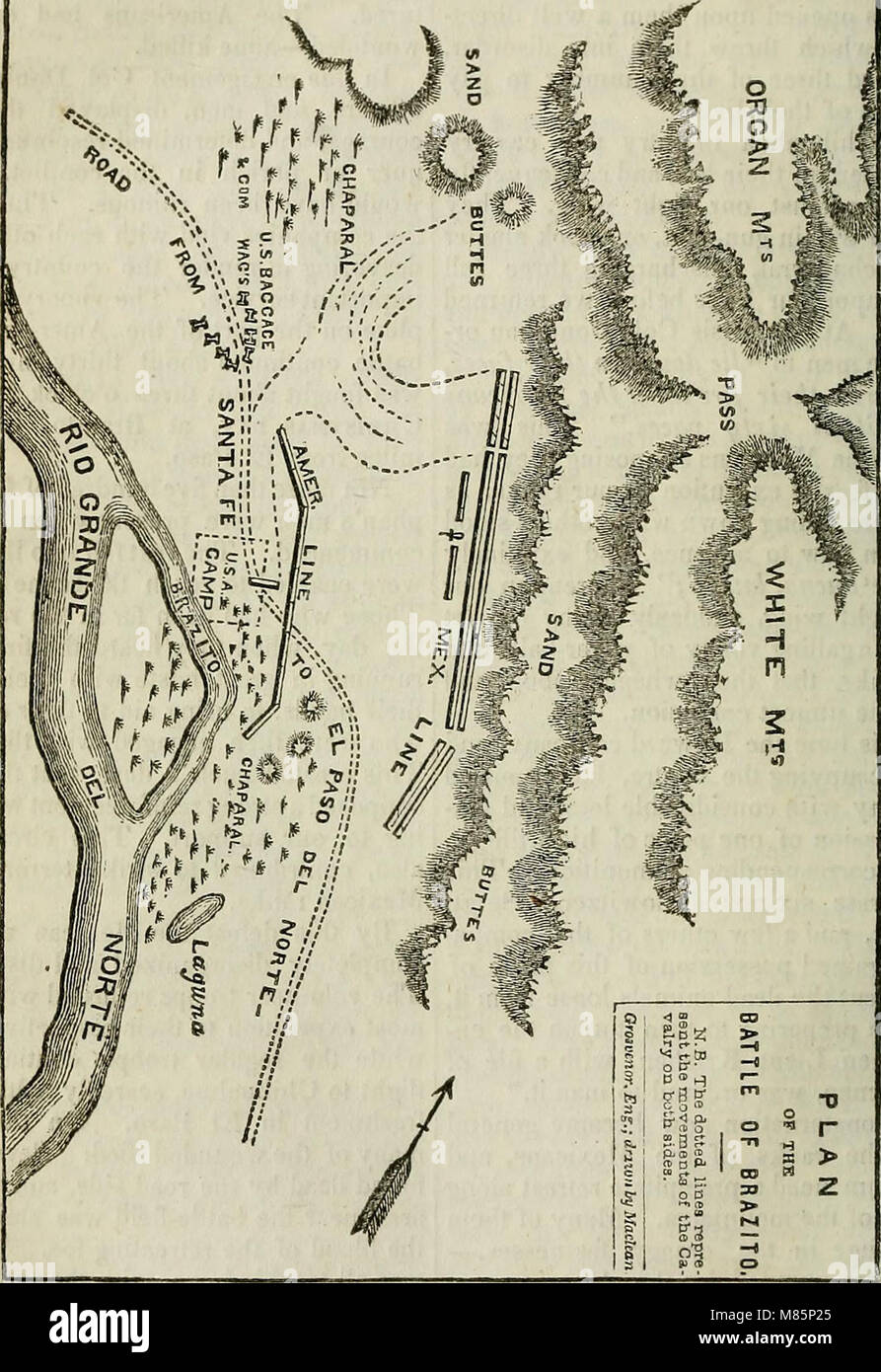

The first major test of their resolve came on Christmas Day, 1846, at the Battle of El Brazito, near modern-day Las Cruces, New Mexico. Doniphan’s men, while camped by the Rio Grande, were attacked by a Mexican force of some 500 soldiers, including dragoons and infantry, commanded by General Antonio Ponce de León. Despite being outnumbered and caught somewhat by surprise, the Missourians quickly formed a defensive line. Their accurate rifle fire and the disciplined charge of their mounted men routed the Mexican forces in a sharp, decisive engagement that lasted less than an hour. It was a crucial victory, bolstering the volunteers’ confidence and proving their mettle against professional soldiers.

Following El Brazito, Doniphan’s expedition pressed deeper into Chihuahua. The Mexican authorities, alarmed by the American advance, began to prepare a more formidable defense. On February 28, 1847, the two forces met at the Battle of Sacramento, a strategically important pass about 15 miles north of Chihuahua City. Here, the Mexicans, under the command of General José A. Heredia, had established a heavily fortified position, numbering around 4,000 men with 16 pieces of artillery, occupying the high ground and surrounding ravines. Doniphan’s force, by contrast, numbered a mere 924 men and six small cannons.

The disparity in numbers and defensive strength was daunting, but Doniphan, with characteristic audacity, devised a brilliant flanking maneuver. Instead of a frontal assault, which would have been suicidal, he ordered his men to bypass the main Mexican fortifications by circling around a dry lake bed to the west. This unexpected move caught the Mexican commanders off guard, forcing them to re-deploy their artillery and men in haste.

As the Americans advanced, a fierce artillery duel erupted. Doniphan’s light cannons, expertly handled by the volunteers, proved surprisingly effective, silencing several Mexican batteries. Then, with the Mexican lines in disarray, Doniphan ordered a series of charges. The Missourians, on foot and mounted, surged forward, their frontier fighting skills and accurate rifle fire proving devastating. The battle was a resounding American victory, achieved against overwhelming odds. Mexican losses were estimated at over 300 killed and wounded, with many more captured, while Doniphan’s force suffered only one killed and 11 wounded.

The Battle of Sacramento effectively opened the gates to Chihuahua City. On March 1, 1847, Doniphan’s weary but triumphant volunteers marched into the city and raised the American flag. They had conquered a vast, strategically important Mexican state with a force that was a fraction of the enemy’s strength. For the next two months, they occupied Chihuahua, administering the city and attempting to establish some semblance of order.

However, their mission was not yet complete. The long-awaited link-up with General Taylor’s forces did not materialize as planned. Instead, Doniphan received new orders: march east to Saltillo, then south to join Taylor’s main army. This meant another march of several hundred miles through hostile territory.

The journey from Chihuahua to Saltillo was less fraught with direct combat but equally challenging in terms of logistics and endurance. Finally, in May 1847, Doniphan’s expedition rendezvoused with General Taylor’s forces near Saltillo. Taylor, who had just won the decisive Battle of Buena Vista, was astonished by the Missourians’ incredible journey and their achievements. He reportedly remarked, "You have made a march as long as the retreat of the Ten Thousand, and have conquered two Mexican states. You are entitled to be called the ‘Modern Argonauts’."

After a brief rest, the volunteers were marched to Matamoros, then transported by steamship to New Orleans. From there, they made their way up the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers, arriving back in St. Louis in July 1847, more than a year after their departure. They were greeted not with grand parades or widespread national acclaim, but with the quiet satisfaction of a job well done. Their enlistment was up, and most simply returned to their farms and businesses, their incredible adventure fading into the background of a nation rapidly expanding its borders.

The statistics of Doniphan’s Expedition are staggering. In just over a year, these citizen soldiers marched approximately 3,600 miles – from Fort Leavenworth to Santa Fe, then to El Paso del Norte, Chihuahua City, Saltillo, and finally to Matamoros – before traveling by sea and river back to Missouri. They fought and won two decisive battles against superior numbers, effectively securing the territories of New Mexico and Chihuahua for the United States, and greatly contributing to the overall American victory in the Mexican-American War. They achieved this with minimal supplies, against a harsh environment, and without the extensive training or logistical support of a regular army.

Doniphan’s Expedition stands as a testament to the resilience, adaptability, and fighting spirit of the American citizen soldier. It was an epic of endurance and courage, a vital chapter in the story of American expansion that, while often overshadowed by larger campaigns, perfectly encapsulates the daring and ambition of a young nation forging its destiny. The dusty, sun-baked trails they traversed and the battles they fought are a poignant reminder that sometimes, the greatest feats are accomplished not by professional armies, but by ordinary men called to extraordinary service, marching into the unknown with an unshakeable will to succeed. They were, indeed, Missouri’s immortal heroes, and their odyssey remains one of the most remarkable military expeditions in history.