Beyond the Pin and the Puppet: Unveiling the Enduring Soul of American Voodoo

New Orleans, Louisiana – The very word "Voodoo" conjures a potent cocktail of images: shadowy figures in moonlit graveyards, dolls pierced with pins, whispered curses, and zombies shuffling through mist-laden swamps. For many, it’s a dark, exotic, and vaguely terrifying relic of a bygone era, confined to horror movies and tourist trap storefronts. Yet, beneath the sensationalized veneer and pervasive misconceptions, American Voodoo and its closely related cousin, Hoodoo, pulse as vibrant, resilient spiritual traditions, deeply woven into the fabric of American history and culture, particularly in the Deep South.

This isn’t merely a collection of spells and superstitions; it is a complex, syncretic spiritual system born from the crucible of the transatlantic slave trade, a testament to the indomitable human spirit’s quest for solace, power, and connection in the face of unimaginable adversity. To understand American Voodoo is to understand a crucial, often overlooked, chapter of the American story.

From African Shores to American Soil: A Genesis of Survival

The roots of American Voodoo stretch back across the Atlantic to the ancient religious traditions of West Africa, primarily those of the Fon, Ewe, and Yoruba peoples of what is now Benin, Togo, and Nigeria. These sophisticated belief systems, rich with ancestor veneration, spirit communication, and a profound connection to the natural world, were forcibly transplanted to the Americas with enslaved Africans.

Deprived of their homes, families, and material possessions, enslaved people clung fiercely to their spiritual heritage. In the brutal environment of the plantations, these practices became more than just religion; they were a source of psychological survival, cultural resistance, and a clandestine form of empowerment. The open practice of African religions was strictly forbidden by slave owners, who feared their unifying and rebellious potential. This suppression forced the traditions underground, leading to a remarkable process of adaptation and syncretism.

"Voodoo, at its heart, is a religion of the oppressed," explains Dr. Ina J. Fandrich, a scholar of African American religions. "It provided a framework for meaning, healing, and even justice in a world that offered none."

This adaptation involved blending African deities and spirits, known as Loa or Lwa, with Catholic saints. For instance, the fierce warrior spirit Ezili Dantor might be represented by the Black Madonna or Mater Dolorosa, while Papa Legba, the opener of the gates, found his counterpart in St. Peter. This syncretism allowed practitioners to outwardly conform to the dominant religion while secretly preserving their ancestral faiths. It was a brilliant, often desperate, act of spiritual camouflage.

While the term "Voodoo" is often used broadly, it’s important to distinguish between Haitian Vodou, a more structured, initiatory religion with a defined priesthood, and American Hoodoo (or Rootwork), which is more of a folk magical practice focused on practical ends like healing, protection, love, and luck, often without a formal congregational structure. In America, particularly in the early days, these lines were often blurred, with practitioners drawing from both traditions.

New Orleans: The Crucible of American Voodoo

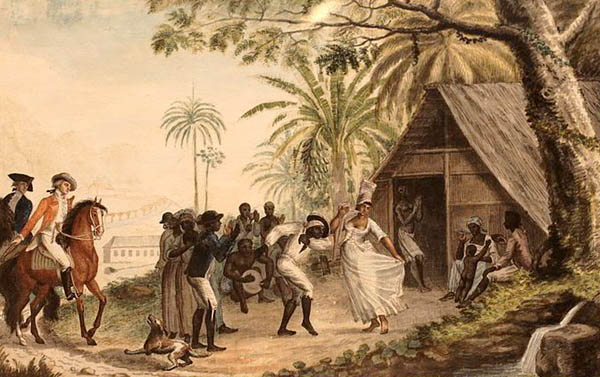

Nowhere did Voodoo flourish more openly and influentially than in New Orleans, Louisiana. Unique among American cities, New Orleans’ French and Spanish colonial heritage, coupled with a large, relatively freer population of gens de couleur libres (free people of color), created a more tolerant environment for African-derived practices. Congo Square, a designated gathering place for enslaved Africans on Sundays, became a vibrant hub where drumming, dancing, and spiritual expression could be openly practiced, laying the groundwork for Voodoo’s public emergence.

The 19th century saw the rise of iconic figures who would forever shape the public perception of American Voodoo. Foremost among them was Marie Laveau, the legendary Voodoo Queen of New Orleans. Born in 1801, Laveau was a free woman of color, a successful hairdresser, and a devout Catholic. Yet, her true power lay in her extraordinary spiritual acumen and her ability to navigate the complex social strata of the city.

Laveau’s Voodoo was not about black magic, but a potent blend of spiritual counseling, healing, rootwork, and political influence. She was sought out by people from all walks of life – black and white, rich and poor – for her ability to provide advice, protection, and remedies. Her power stemmed from her deep knowledge of herbs, rituals, and human nature, and her profound connection to the spirits. She conducted public rituals at Lake Pontchartrain and Bayou St. John, drawing crowds and cementing her reputation.

"Marie Laveau wasn’t just a Voodoo practitioner; she was a social engineer," writes Martha Ward in her book "Voodoo Queen: The Spirited Lives of Marie Laveau." "She built a network of informants and clients that gave her unparalleled insight into the city’s affairs, making her one of the most powerful women in 19th-century New Orleans."

Another significant figure was Dr. John Montenee, also known as Bayou John or Prince John, an African-born practitioner who predated Laveau and was known for his potent gris-gris (charms or amulets) and healing abilities. These figures, and many others, laid the foundation for a spiritual tradition that offered community, agency, and a sense of dignity to a marginalized population.

The Misunderstood Art: Debunking the Myths

The sensationalized image of Voodoo, however, has largely overshadowed its true nature. Hollywood, pulp fiction, and yellow journalism have relentlessly portrayed Voodoo as inherently evil, focusing on the most lurid aspects. The infamous "Voodoo doll" is perhaps the most egregious example of this misrepresentation.

While effigies have been used in various magical traditions worldwide (including European folk magic) to represent individuals for both benevolent and malevolent purposes, the pin-pierced doll as a central, malicious tool of Voodoo is largely a fabrication. Traditional Vodou and Hoodoo often use effigies for healing or drawing someone closer, not typically for inflicting harm. The popular image is a distortion, designed to demonize and exoticize.

The concept of "zombies" is another potent example. In Haitian Vodou, a zombi is a person whose soul has been captured or whose body has been reanimated through a complex ritual, often seen as a punishment for severe transgressions. It is a nuanced concept within a specific cultural context, far removed from the flesh-eating ghouls of modern horror films.

These pervasive myths have had real consequences, fostering fear, discrimination, and a profound lack of understanding of a legitimate spiritual path. They obscure Voodoo’s true focus on balance, healing, protection, community, and the veneration of ancestors and spirits who guide and assist practitioners in navigating life’s challenges.

Voodoo in the 21st Century: Resilience and Reawakening

Today, American Voodoo and Hoodoo are experiencing a resurgence, moving beyond the confines of New Orleans and into the wider spiritual landscape. Practitioners across the United States are embracing these traditions, drawn by a desire for ancestral connection, self-empowerment, and a holistic approach to spirituality.

The internet has played a significant role in this reawakening, providing platforms for learning, community building, and dispelling misinformation. Modern practitioners, often well-educated and diverse, are reclaiming the narrative, emphasizing the healing, protective, and empowering aspects of their faith. They engage in rootwork, create gris-gris bags, consult with ancestors and spirits, and perform rituals for love, luck, success, and spiritual cleansing.

However, this modern resurgence also brings new challenges, including issues of cultural appropriation. As Voodoo and Hoodoo become more visible, there’s a delicate balance between respectful engagement and the commodification of sacred practices by those outside the tradition, often without proper understanding or reverence.

Despite the challenges, the spirit of American Voodoo endures. It stands as a powerful testament to the resilience of human belief, the ingenuity of cultural adaptation, and the enduring quest for meaning and connection. It is a living heritage, a spiritual mosaic forged in adversity, offering a unique lens through which to view the complex tapestry of American religious life.

From the drumbeats in Congo Square to the quiet altars in modern homes, American Voodoo continues to whisper its stories – stories of survival, defiance, healing, and a profound connection to the seen and unseen worlds. It is far more than pins and puppets; it is the enduring soul of a people, a spiritual tradition that refuses to be silenced, misunderstood, or forgotten. It is, in essence, a profound expression of American freedom and identity.