Whispers of the Serpent: Unveiling the Sacred Secrecy of the Hopi Snake Dance

In the arid expanse of northeastern Arizona, perched atop ancient mesas that rise like islands from a sea of scrub brush, lies the homeland of the Hopi people. For centuries, these agriculturalists have maintained a profound spiritual connection to the land, their lives inextricably linked to the whims of the sky. Among their most sacred and enigmatic rituals, one stands paramount in its power and secrecy: the Hopi Snake Dance. A millennia-old prayer for rain, fertility, and the renewal of life, this ceremony, rarely witnessed by outsiders today, embodies the very essence of Hopi cosmology and their enduring bond with the natural world.

Once an infrequent spectacle for curious ethnographers and adventurous tourists, the Snake Dance has, in recent decades, retreated further into the private sphere of Hopi religious life. This heightened secrecy is a deliberate act of protection, a response to decades of misinterpretation, exploitation, and disrespect. The Hopi have made it clear: this is not a performance or a show, but a deeply reverent and dangerous spiritual endeavor. To understand it, one must look beyond the sensational and delve into the intricate web of Hopi belief that underpins every gesture and chant.

Roots in Ancient Earth: The Hopi Way of Life

The Hopi, whose name translates to "Peaceful People," are one of the oldest continuously inhabited communities in North America, with ancestral roots stretching back thousands of years. Their existence in a harsh, high-desert environment has fostered an unparalleled reliance on rain. Water is not merely a resource; it is life itself, a sacred blessing from the cloud people, the kachinas. Their complex ceremonial calendar, spanning the entire year, is dedicated to maintaining harmony with the cosmos and ensuring the cycles of nature — particularly the crucial summer rains that nourish their cornfields.

The Snake Dance, or Tsu’tiki, is performed biennially, alternating with the Flute Dance, typically in late August. It is the culmination of a nine-day ceremonial cycle, primarily orchestrated by two of the Hopi religious fraternities: the Antelope Society (Chaptu’u) and the Snake Society (Tsu’tsu’t). These societies are not merely clubs but ancient lineages of knowledge, responsible for preserving and executing the intricate rituals passed down through generations.

The Nine-Day Vigil: Preparation and Purification

The visible public dance is merely the tip of a vast iceberg of sacred preparation. The nine days preceding the public ceremony are spent in deep seclusion within the kivas – subterranean ceremonial chambers that symbolize the underworld and the place of emergence. Here, the priests engage in fasting, purification rites, chanting, and the construction of elaborate sand paintings. These ephemeral artworks, meticulously crafted from colored sands, depict sacred symbols, lightning, rain clouds, and the serpentine paths of water. They serve as altars, conduits for spiritual power, and blueprints for the cosmic order the ceremony seeks to invoke.

During this period, members of the Snake Society undertake the perilous task of gathering the serpents. This is not a hunt, but a reverent collection. Armed with special snake sticks and eagle feathers, they venture into the four cardinal directions, respectfully coaxing rattlesnakes, bullsnakes, garter snakes, and other non-venomous species from their dens. Each snake is treated with immense respect, seen not as a creature to be feared, but as a living prayer, a messenger between the human world and the underworld, carrying the Hopi’s urgent petitions for rain. The snakes are then brought back to the kiva, where they are washed, calmed, and housed in sacred vessels. It is believed that the snakes, through their intimate connection to the earth, can carry the prayers of the Hopi directly to the cloud deities and ancestral spirits dwelling below.

The Dance Unveiled: A Public Prayer

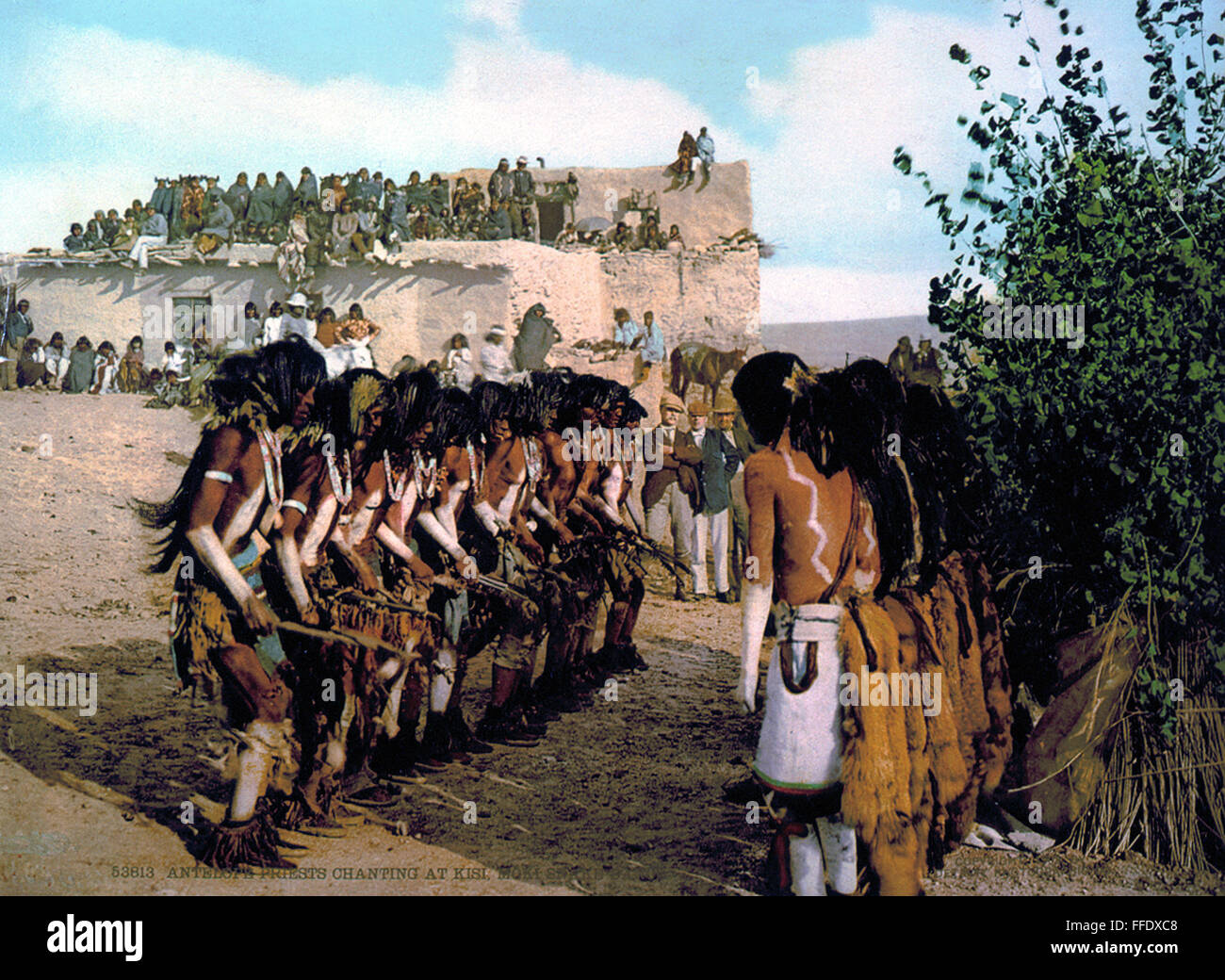

On the morning of the ninth day, the main public ceremony unfolds in the village plaza, usually around sunset. The scene is one of stark, ancient beauty. The village women and children gather on the rooftops, while men and a few invited guests line the plaza edges. A central cottonwood bower, or kisi, stands as a symbolic entrance to the underworld, a place of emergence for the dancers.

The ceremony begins with the Antelope Priests emerging from the kiva, adorned with traditional body paint, kilts, and elaborate headresses, often featuring corn and other symbols of fertility. They circle the plaza four times, sprinkling cornmeal and setting down sacred objects. Their chants are deep and resonant, invoking the spirits of rain and growth.

Then, the Snake Priests emerge, their bodies painted with striking black and white designs, often depicting snakes or lightning. They carry their own sacred objects, including a pouch of cornmeal and a snake whip – typically an eagle feather or a stick. The air crackles with anticipation.

The heart of the ceremony involves the Snake Priests taking live snakes, often venomous rattlesnakes, from the kisi. Each priest is accompanied by a "whip man" or "wiper," who follows closely, using an eagle feather or a snake stick to distract the snake’s head and prevent it from coiling or striking the dancer. The main dancer holds the snake firmly in his mouth, often just behind the head, or sometimes cradles it in his arms as he dances around the plaza. The sight of a man dancing with a live rattlesnake in his mouth is undoubtedly unnerving to an uninitiated observer, but for the Hopi, it is an act of profound faith and communion.

The dancers move in a rhythmic, shuffling gait, their bare feet pounding the earth, symbolizing their connection to the land and the vibrations of the underworld. They circle the plaza repeatedly, their movements mirroring the serpentine path of lightning and flowing water. The chants grow louder, a hypnotic chorus of prayers for rain. As the dance progresses, more snakes are brought out, sometimes dozens at a time, until the plaza is alive with the movements of men and reptiles.

At a certain point, the snakes are carefully placed on a large circle of cornmeal drawn on the ground, forming a writhing, living mound. The Snake Priests surround this circle, sprinkling it with cornmeal and offering intense prayers. Then, in a swift, coordinated movement, the dancers scoop up the snakes, holding several in their arms and mouths. They run to the edges of the mesa and, with a final prayer, release the snakes into the wild, sending them back to the earth to carry the Hopi’s supplications directly to the rain gods and ancestors in the underworld.

Following the release, the Snake Priests quickly return to the kiva, where they undergo a powerful emetic purification ritual, often inducing vomiting. This is believed to cleanse them of any negative influences or potential venom, ensuring their spiritual and physical purity after handling the sacred creatures.

The Serpent’s Significance: More Than Just Reptiles

For the Hopi, the snake is far more than a mere reptile. It is a potent symbol of life, death, rebirth, and the cyclical nature of existence. Snakes shed their skin, symbolizing renewal and transformation. Their movements mimic lightning, and their subterranean existence connects them directly to water, springs, and the underworld, where the kachinas reside. They are considered "brothers" to the Hopi, messengers between the realms, and direct conduits for prayers.

The act of holding the venomous snake in the mouth is not a test of courage or a demonstration of power over nature, but an act of profound humility and unity. It symbolizes the dancer’s willingness to absorb the snake’s power and to become one with the natural forces he seeks to influence. The rare instances of snakebites during the ceremony are not seen as failures, but as part of the inherent risk of engaging with such potent spiritual energy, and the priests are believed to possess antidotes or spiritual immunity.

Guardians of Tradition: Challenges and Misconceptions

The Hopi Snake Dance has long fascinated and, at times, horrified the outside world. Early ethnographers and photographers often sensationalized the ceremony, focusing on the danger rather than the deep spiritual meaning. This commodification of a sacred ritual, coupled with a general lack of understanding and respect from tourists, ultimately led the Hopi to severely restrict access.

Today, photography, filming, and even detailed note-taking are strictly forbidden. The Hopi have asserted their right to cultural self-determination, to protect their traditions from exploitation and misrepresentation. They emphasize that the ceremony is not for entertainment, but a vital, living prayer for their survival and the well-being of the entire world.

Misconceptions abound: that the snakes are defanged or drugged (they are not); that it’s a form of snake charming (it is not); or that it’s a display of human dominance over animals (it’s the opposite – a communion). For the Hopi, the dance is a profound act of reciprocity, an offering of prayer and respect to the powerful forces of nature that sustain them.

A Timeless Prayer for Life

In a world increasingly disconnected from the natural environment, the Hopi Snake Dance stands as a powerful testament to an ancient worldview where humanity is intricately woven into the fabric of the cosmos. It is a timeless prayer for rain, not just for their cornfields, but for the sustenance of all life. It is a profound act of faith, humility, and courage, performed to ensure the continuation of the world as they know it.

Though largely unseen by outsiders, the Hopi Snake Dance continues to be performed with unwavering devotion in the secluded plazas of the mesa villages. It is a vibrant, living tradition, echoing the whispers of the serpent as it carries the hopes and prayers of the Peaceful People, linking earth to sky, past to present, and humanity to the enduring rhythms of creation. It is a stark reminder that true spirituality often resides not in grand displays, but in the quiet, reverent acts of connection to the very pulse of life itself.