Nevada’s Enduring Veins: Digging for Riches in the Silver State’s Arid Future

Beyond the neon glow of Las Vegas and the shimmering surface of Lake Tahoe, lies the true heart of Nevada: a vast, rugged expanse of desert and mountain ranges, etched with the scars and triumphs of over a century and a half of mining. This is the Silver State, a moniker born from the mineral wealth that first lured prospectors and fueled its very existence. Today, the process of "placing a mine" in Nevada is far removed from the pickaxe and pan of the 19th century; it is a complex, multi-billion-dollar endeavor, a delicate dance between economic opportunity, environmental stewardship, and the relentless global demand for the Earth’s hidden treasures.

Nevada remains the undisputed leader in gold production in the United States, and a significant global player. But the state’s mineral narrative is rapidly evolving. While gold, silver, and copper continue to be vital, the 21st century has introduced a new, electrifying element to the mining equation: lithium. The "white gold" of the electric vehicle revolution, lithium’s extraction in Nevada is not just about digging for riches; it’s about powering the future, often in the face of deeply entrenched environmental and social concerns.

A Legacy Forged in Ore: From Comstock to Modern Gold Rushes

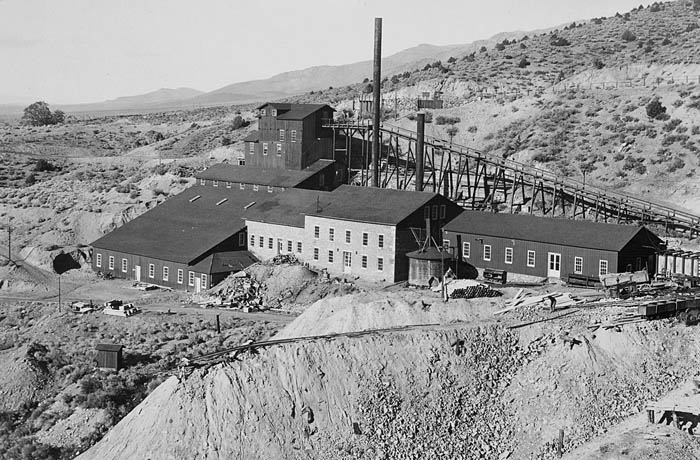

To understand modern Nevada mining, one must first acknowledge its foundational myth: the Comstock Lode. Discovered in 1859 near present-day Virginia City, this colossal deposit of silver and gold ignited one of the greatest mining rushes in American history. It poured billions (in today’s dollars) into the national economy, financed the Union cause during the Civil War, and transformed Nevada from a sparsely populated territory into a state in just five years. The Comstock’s legacy is etched into the very identity of Nevada, fostering a deep-seated appreciation for the independent spirit of the prospector and the economic power of subterranean wealth.

"Nevada’s history is literally built on mining," explains Dr. Robert R. Reno, a historian specializing in Western expansion. "The Comstock wasn’t just a mine; it was a catalyst that shaped our laws, our economy, and our culture. That spirit, the idea of finding wealth hidden beneath the surface, still resonates today, albeit in a much more industrialized form."

Today, the "gold rush" continues, though driven by global markets and sophisticated geology rather than individual fortune-seekers. Vast open-pit mines, like those on the Carlin Trend – one of the richest gold deposits in the world – dominate the landscape. These operations extract microscopic gold particles from massive volumes of rock, a far cry from the visible veins of the Comstock.

The Modern Quest: From Exploration to Extraction

Placing a modern mine in Nevada is an arduous journey, typically spanning years, if not decades, and costing hundreds of millions, sometimes billions, of dollars before the first ounce of saleable material is produced.

1. Exploration and Discovery: It begins with geologists. Utilizing advanced seismic imaging, geochemical analysis, and satellite data, they search for tell-tale signs of mineral deposits deep beneath the surface. Once a promising anomaly is identified, extensive drilling campaigns are initiated to define the size, grade, and accessibility of the ore body. This phase alone can cost tens of millions and offers no guarantee of a viable mine.

2. Claiming and Permitting: Under the General Mining Law of 1872, a relic of the Comstock era, mineral exploration and extraction on federal lands (which constitute over 85% of Nevada) are generally permitted. Companies stake claims, but this is merely the first step. The true gauntlet is the permitting process. This involves a labyrinthine array of federal and state agencies, including:

- Bureau of Land Management (BLM): The primary federal regulator for mining on public lands, responsible for environmental reviews and land use planning.

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA): Oversees air and water quality, hazardous waste, and ensures compliance with federal environmental laws.

- Nevada Division of Environmental Protection (NDEP): Manages state-level environmental regulations, including water pollution control permits, air quality permits, and reclamation plans.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: Consulted for impacts on endangered species and critical habitats.

- State Engineer’s Office: Manages water rights, a crucial and contentious issue in arid Nevada.

"The permitting process is designed to be rigorous, and rightly so," states Sarah Jenkins, a former BLM official. "Companies must demonstrate not only the economic viability of their project but also their capacity to minimize environmental harm, protect water resources, and reclaim the land once operations cease. It’s a testament to balancing resource development with public interest."

This phase involves extensive environmental impact statements (EIS), public comment periods, and often, legal challenges from environmental groups and local communities. A single EIS can run thousands of pages and take five to ten years to complete.

3. Development and Construction: Once permits are secured, the real work of "placing" the mine begins. This involves massive earthmoving operations, building roads, power lines, and pipelines. For open-pit mines, this means excavating colossal amounts of overburden to reach the ore. Processing facilities, often involving cyanide heap leaching for gold or complex chemical processes for lithium, are constructed. Tailings dams, designed to hold the waste rock and processing byproducts, are engineered to withstand earthquakes and prevent leakage.

Economic Engines and Environmental Crossroads

The economic impact of mining in Nevada is undeniable. The industry provides thousands of high-paying jobs, both directly at the mines and indirectly through suppliers and service providers. It generates significant tax revenue for the state and local governments, funding schools, infrastructure, and public services. In many rural Nevada counties, mining is the largest, if not the sole, economic driver.

"Our town would simply not exist without the mine," says Maria Rodriguez, a long-time resident of Elko, a major mining hub. "It provides stable jobs, allows our kids to stay here, and supports all the local businesses. It’s not just a hole in the ground; it’s our livelihood."

However, this economic boon comes with substantial environmental costs and community concerns.

Water Consumption: In one of the driest states in the nation, mining operations are incredibly water-intensive. Water is used for dust suppression, ore processing, and for the mining camps themselves. Securing water rights is a complex and often litigious process, pitting mining companies against agricultural interests, growing urban areas, and environmental advocates who fear the depletion of precious aquifers.

Land Disturbance and Habitat Loss: Open-pit mines create vast scars on the landscape, altering topography and destroying natural habitats. While reclamation plans are legally mandated to restore disturbed areas to a productive post-mining land use, the scale of some operations means complete ecological restoration is often impossible within a human timeframe.

Waste Management: Mining generates enormous quantities of waste rock and tailings, which can contain heavy metals and other contaminants. If not properly managed, these can leach into groundwater or surface water, leading to acid mine drainage and long-term pollution. Tailings dams, while engineered for safety, pose a perpetual risk of failure, as tragically demonstrated in other parts of the world.

Social and Cultural Impacts: The boom-and-bust nature of mining can strain small communities, leading to housing shortages, increased traffic, and social changes. For Native American tribes, mining projects often infringe upon ancestral lands, sacred sites, and traditional cultural practices, leading to profound spiritual and legal conflicts. The proposed Thacker Pass lithium mine in northern Nevada, for instance, has faced fierce opposition from the Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribe, who consider the site sacred.

The Lithium Frontier: A New Kind of Rush

The focus on lithium in Nevada marks a significant shift. The state’s unique geology, particularly in the arid playas and ancient lakebeds, holds some of the largest known lithium reserves in North America. As the world transitions to electric vehicles and renewable energy storage, the demand for lithium has skyrocketed.

"Nevada is poised to become a critical component of the global clean energy supply chain," asserts Dr. Anya Sharma, a materials scientist and energy policy expert. "Developing our domestic lithium resources is not just an economic opportunity; it’s a strategic imperative for national security and climate goals. However, the environmental footprint, particularly around water use and land disturbance for these new types of mines, needs careful scrutiny."

The methods for extracting lithium vary, from traditional hard rock mining to extracting lithium-rich brines from underground aquifers. Both methods present distinct environmental challenges, reigniting familiar debates about resource extraction in a fragile desert ecosystem. The promise of "green energy" collides directly with the very real, often brown, impacts of mining.

The Balancing Act: A Future of Responsible Extraction?

Placing a mine in Nevada today is an exercise in complex trade-offs. The state stands at a crossroads, balancing its historical identity as a mining powerhouse with the urgent need for environmental protection and sustainable development.

Technological advancements, such as automation, remote sensing, and more efficient processing techniques, are helping to reduce the footprint of modern mines. Companies are investing in better water management strategies, including recycling and desalination, and improved reclamation practices. The regulatory framework, though imperfect, is far more robust than in the Comstock era, demanding accountability and planning for post-closure landscapes.

Ultimately, the decision to place a mine in Nevada is not merely a geological or economic calculation; it’s a societal one. It involves weighing the undeniable benefits of domestic resource production, high-paying jobs, and critical materials for a changing world against the very real environmental costs, the preservation of fragile ecosystems, and the rights of indigenous communities.

As the sun sets over Nevada’s vast, mineral-rich landscapes, the debate continues. The hum of heavy machinery echoes through the canyons, a constant reminder that the Silver State’s destiny, now more than ever, remains inextricably linked to what lies beneath its ancient, sun-baked surface. The quest for riches endures, but the definition of true wealth in Nevada is increasingly expanding to encompass not just the gold and lithium we extract, but also the precious land and water we strive to protect.