Echoes of the Pacific: The Enduring Legacy of the First Hawaiians

Imagine a speck in the vast, shimmering expanse of the Pacific, a cluster of volcanic islands born of fire and ocean, lush and untouched. Now, imagine a people, thousands of miles away, possessed of an unyielding spirit and an almost unimaginable mastery of the sea, who set out in double-hulled canoes to find it. This is the epic saga of the First Hawaiians, a story not merely of migration, but of audacious exploration, ingenious adaptation, and the forging of one of the most sophisticated indigenous societies the world has ever known.

Their journey began not in a single moment, but over centuries, a testament to the persistent westward expansion of Polynesian seafarers. While the exact origins are still debated by scholars, the consensus points to a series of migrations from the Marquesas Islands and later from Tahiti, spanning from roughly 300 to 800 CE. These were not accidental drift voyages; they were meticulously planned expeditions, undertaken by expert navigators who read the ocean like a book.

“Our ancestors were the NASA of their time,” asserts Nainoa Thompson, the renowned Hawaiian master navigator who revived traditional voyaging techniques with the Hōkūleʻa canoe. “They sailed by the stars, the sun, the swells, the winds, and the birds. They carried entire ecosystems in their canoes – plants, animals, and the knowledge to make new homes.”

Masters of the Star Compass

The feats of these ancient mariners defy modern comprehension. Lacking compasses or sextants, they navigated by a profound understanding of the natural world. Their primary tool was the “star compass” – a mental construct of 32 points on the horizon, each corresponding to a rising or setting star. They memorized the movements of hundreds of celestial bodies, could discern subtle shifts in wave patterns caused by distant landmasses, interpret cloud formations, and follow the migratory paths of birds.

Their vessels, the wa’a kaulua (double-hulled canoes), were marvels of engineering. Ranging from 50 to over 100 feet in length, they were capable of carrying dozens of people, plants, animals, tools, and provisions across thousands of miles of open ocean. These voyages were not just about finding land; they were about settling it, bringing with them the seeds of a new civilization.

Upon arrival, these intrepid pioneers found a pristine archipelago, geologically young and isolated, dominated by towering volcanoes and verdant valleys. It was a blank canvas, rich in resources but lacking many of the staples of their ancestral homes. The challenge was immense: to transform a wild landscape into a sustainable living environment.

Forging a New World: The Ahupua’a System

The Hawaiians met this challenge with unparalleled ingenuity. They brought with them the “canoe plants” – kalo (taro), uala (sweet potato), mai’a (banana), niu (coconut), ‘ulu (breadfruit), and ‘ohi’a ‘ai (mountain apple), among others. They also introduced pigs, chickens, and dogs. They cleared land, built elaborate irrigation systems (like the sophisticated taro pondfields), and developed sustainable fishing practices.

Central to their success was the ahupua’a system, a unique and highly efficient land management model. Each ahupua’a was a wedge-shaped land division, typically extending from the mountain uplands (where forests provided timber and fresh water) down through the fertile valleys to the fishing grounds of the coast. This “ridge-to-reef” approach ensured that every community had access to all necessary resources – fresh water, agricultural land, timber, and marine life – and fostered a deep sense of responsibility for the health of the entire ecosystem. It was an early and effective form of integrated resource management, long before the term was coined in the West.

A Society Built on Mana and Kapu

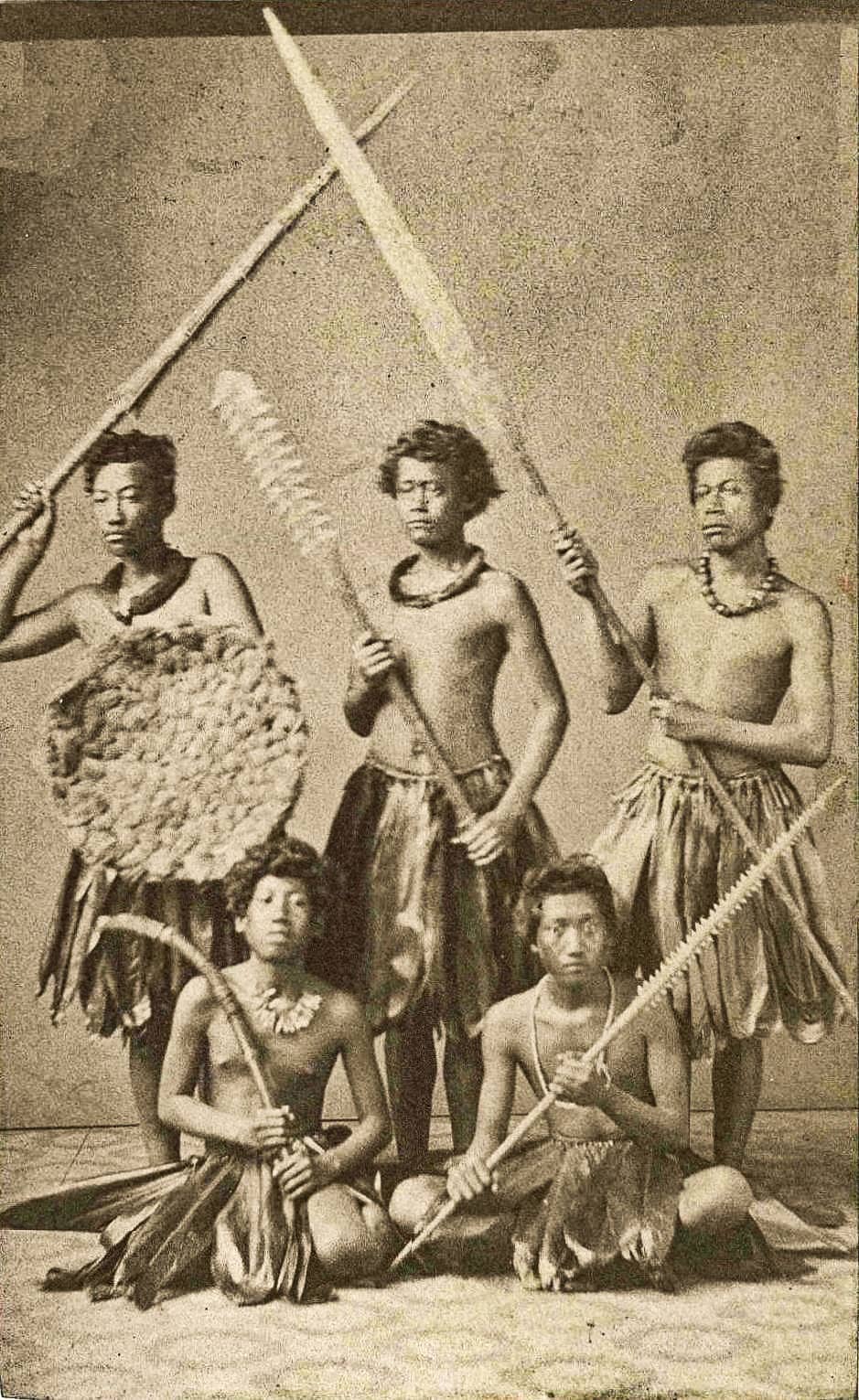

Over centuries, the isolated Hawaiian islands fostered a distinctive and highly structured society. At its apex were the ali’i (chiefs), believed to possess mana (spiritual power and authority) inherited from divine ancestors. Below them were the kahuna (priests, master craftsmen, healers, and experts in various fields), the maka’ainana (commoners, who comprised the majority and worked the land and sea), and the kauwa (an outcast or servant class, though not true slaves in the Western sense).

The fabric of this society was interwoven with a complex system of laws and taboos known as kapu. The kapu governed every aspect of life, from when and where one could fish, to the cultivation of certain crops, to interactions between genders and social classes. For instance, women were forbidden from eating certain foods like pork and bananas, and from eating with men. Certain fishing grounds were kapu during spawning seasons to ensure sustainability. While sometimes seen as restrictive, the kapu system served to maintain social order, conserve resources, and uphold the spiritual sanctity of the community.

“The kapu system, in its essence, was a form of environmental and social governance,” notes Dr. Kealoha Pihana, a Hawaiian cultural historian. “It ensured the perpetuation of resources and maintained the balance between the human and spiritual worlds. It was a sophisticated system for a sophisticated people.”

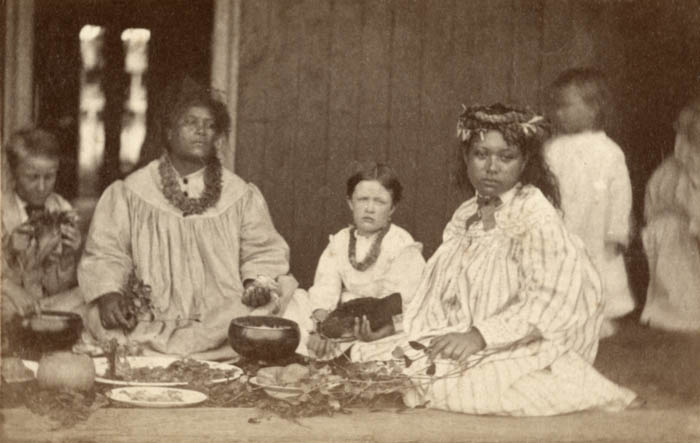

Cultural Flourishing: Hula, Kapa, and Oral Tradition

Hawaiian culture flourished, rich in artistry, spirituality, and oral tradition. Hula, far from being mere entertainment, was a sacred dance form used to recount histories, genealogies, myths, and prayers. Each movement, each chant, told a story, preserving the past for future generations. The creation of kapa (bark cloth), meticulously pounded from the inner bark of various trees, was another high art form, used for clothing, bedding, and ceremonial purposes, often dyed and decorated with intricate patterns.

Oral tradition was paramount. Without a written language, genealogies (mo’oku’auhau), epic poems, chants (oli), and stories (mo’olelo) were memorized and passed down with astonishing accuracy. This ensured that the knowledge of their ancestors, their history, and their relationship to the land and gods remained vibrant. The Hawaiian pantheon of gods – Kāne (god of creation, fresh water), Lono (god of fertility, peace, agriculture), Kū (god of war, politics), and Kanaloa (god of the ocean, healing) – permeated daily life, with rituals and offerings performed to honor them and ensure prosperity.

The Edge of Change

For over a millennium, the First Hawaiians lived in relative isolation, their society evolving, adapting, and expanding across the archipelago. Inter-island rivalries and wars between competing ali’i were common, leading to the gradual consolidation of power into larger chiefdoms. This political evolution was on a trajectory towards unification, a process that would ultimately culminate with Kamehameha the Great just as European contact was becoming a regular occurrence.

The arrival of Captain James Cook in 1778 marked an irreversible turning point, ushering in an era of profound change, disease, and ultimately, the loss of sovereignty. But the story of the First Hawaiians is not defined by this contact, but by what came before: the remarkable journey, the ingenious settlement, and the creation of a thriving, self-sufficient civilization.

An Enduring Legacy

Today, the legacy of the First Hawaiians is more vibrant than ever. The cultural renaissance of recent decades has seen a resurgence of the Hawaiian language, the revival of traditional voyaging, the flourishing of hula, and a renewed focus on sustainable practices rooted in the ahupua’a concept. Modern Hawaiians, and indeed all who call these islands home, draw strength and inspiration from the courage, intelligence, and deep connection to the land and sea demonstrated by their ancestors.

The story of the First Hawaiians is a powerful reminder of humanity’s capacity for exploration, adaptation, and the creation of a harmonious society in even the most challenging environments. Their echoes resonate through the islands’ landscapes, in the wisdom of their language, and in the enduring spirit of a people who dared to sail beyond the horizon and build a world anew. Their journey remains one of humanity’s greatest adventures, a testament to an indomitable spirit that continues to inspire.