The Silent Gaze of Mexico: Manuel Álvarez Bravo’s Poetic Lens

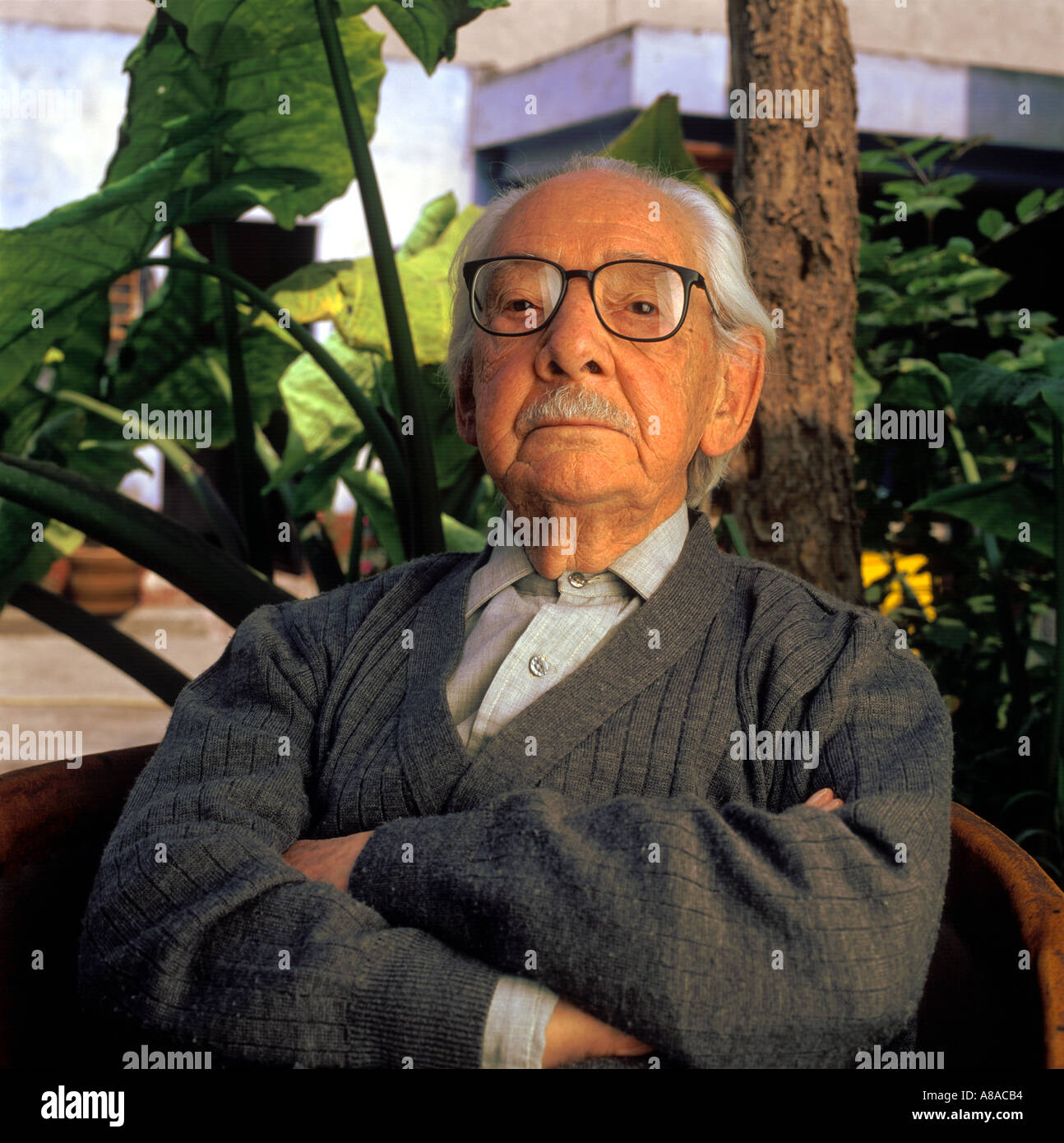

Manuel Álvarez Bravo is not merely a name in the annals of photography; he is a cornerstone, a towering figure whose lens peered into the soul of Mexico, capturing its multifaceted reality with an unparalleled blend of poetic sensibility, incisive observation, and profound mystery. Spanning a career that stretched across nearly eight decades and witnessed the entirety of the 20th century, Álvarez Bravo’s work transcended mere documentation, elevating photography to an art form capable of expressing the ineffable, the dreamlike, and the deeply human. His images, almost exclusively in stark, evocative black and white, are not just photographs; they are visual poems, silent meditations on life, death, and the vibrant, often enigmatic spirit of his homeland.

Born in Mexico City in 1902, Manuel Álvarez Bravo came of age in a nation undergoing a profound cultural renaissance following the Mexican Revolution. This period, characterized by a fervent re-evaluation of Mexican identity – mexicanidad – and a rejection of European cultural dominance, deeply shaped his artistic perspective. While he initially pursued painting and music, it was photography that ultimately captivated him. Largely self-taught, he began experimenting with a Kodak box camera in his late teens, quickly demonstrating an intuitive grasp of composition and light.

His early encounters with American photographers Edward Weston and Tina Modotti, who were living and working in Mexico during the late 1920s, proved pivotal. While they shared technical knowledge and artistic dialogue, Álvarez Bravo offered them a unique, authentic lens through which to view Mexico, distinct from the exoticized gaze of many foreign artists. Modotti, recognizing his extraordinary talent, even gave him her camera and darkroom equipment when she was expelled from Mexico in 1930. This act of generosity effectively launched his professional career, solidifying his commitment to the medium.

Álvarez Bravo’s photographic philosophy was one of deep engagement with his surroundings, yet always filtered through a contemplative and often enigmatic vision. He famously stated, "My camera is merely an excuse to get to know the world." This sentiment underscores his approach: photography was not about imposing a preconceived notion, but about patiently observing, allowing the world to reveal its hidden layers. He was drawn to the everyday – street scenes, markets, children, workers, religious rituals – but imbued these ordinary subjects with extraordinary depth and resonance.

One of the defining characteristics of Álvarez Bravo’s work is its subtle, distinctly Mexican brand of surrealism. Unlike the European surrealists who often fabricated dreamlike scenarios, Álvarez Bravo found the surreal embedded within the fabric of Mexican reality itself. As André Breton, the father of Surrealism, declared during his visit to Mexico in 1938, it was "the surrealist country par excellence." Álvarez Bravo’s photographs often feature unexpected juxtapositions, a sense of suspended time, or a quiet, unsettling mystery that hints at narratives beyond the frame. Images like "Parábolas ópticas" (Optical Parables, 1931), which features a woman standing by a shop window displaying glass eyes, or "Juego de papel" (Paper Game, 1929), depicting a child playing with torn paper on the street, evoke a sense of wonder and disquiet, transforming the mundane into the magical.

Death, a pervasive theme in Mexican culture, is another recurring motif in his oeuvre, approached with a characteristic blend of frankness and poetic contemplation rather than sensationalism. His iconic photograph "Obrero en huelga, asesinado" (Striking Worker, Assassinated, 1934) is a powerful example. It depicts a man lying dead on the ground, his face partially obscured, his hand clutching a newspaper. Crucially, above his head, a sign with an advertising slogan for "Optica" (optics) and "Lentes para ver bien" (Lenses to see well) is visible. The stark irony of the sign next to the lifeless body speaks volumes about the fragility of life and the indifferent world. It’s a profound comment on social injustice, but also a universal meditation on the finality of existence, rendered with a chilling, almost detached beauty.

Álvarez Bravo was a master of composition, utilizing available light to create images of exquisite tonal range and depth. His photographs often possess a sculptural quality, with strong geometric lines and a careful balance of forms. He eschewed dramatic action, preferring stillness and silence, which allowed the viewer to engage more deeply with the emotional and symbolic content of the image. "I try to present things so that they become strange," he once explained, highlighting his deliberate attempt to disrupt conventional perception and invite contemplation. This quality of quiet introspection is evident in photographs like "Los agachados" (The Hunkered Down, 1934), where a group of men eating on the street become an anonymous, almost abstract study of form and posture, imbued with a quiet dignity.

His influence extended beyond the borders of Mexico. He was a contemporary and friend of many significant artists and intellectuals, including Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, with whom he shared a vibrant cultural milieu. In the late 1930s, he co-founded the Mexican Photography Agency with Henri Cartier-Bresson, fostering a crucial exchange of ideas between Mexican and European photographic traditions. His work found international recognition early on, exhibited in major institutions and published in influential journals, establishing his reputation as a leading figure in modern photography.

Manuel Álvarez Bravo’s legacy is multifaceted. He played a crucial role in establishing photography as a legitimate art form in Mexico, moving it beyond mere documentation or commercial application. He forged a distinctly Mexican photographic aesthetic that was both rooted in local culture and universally resonant, demonstrating that a deep engagement with one’s own identity could produce art of global significance. His subtle, poetic approach offered an alternative to the more overt political or documentary styles prevalent at the time, proving that quiet observation could yield profound insights.

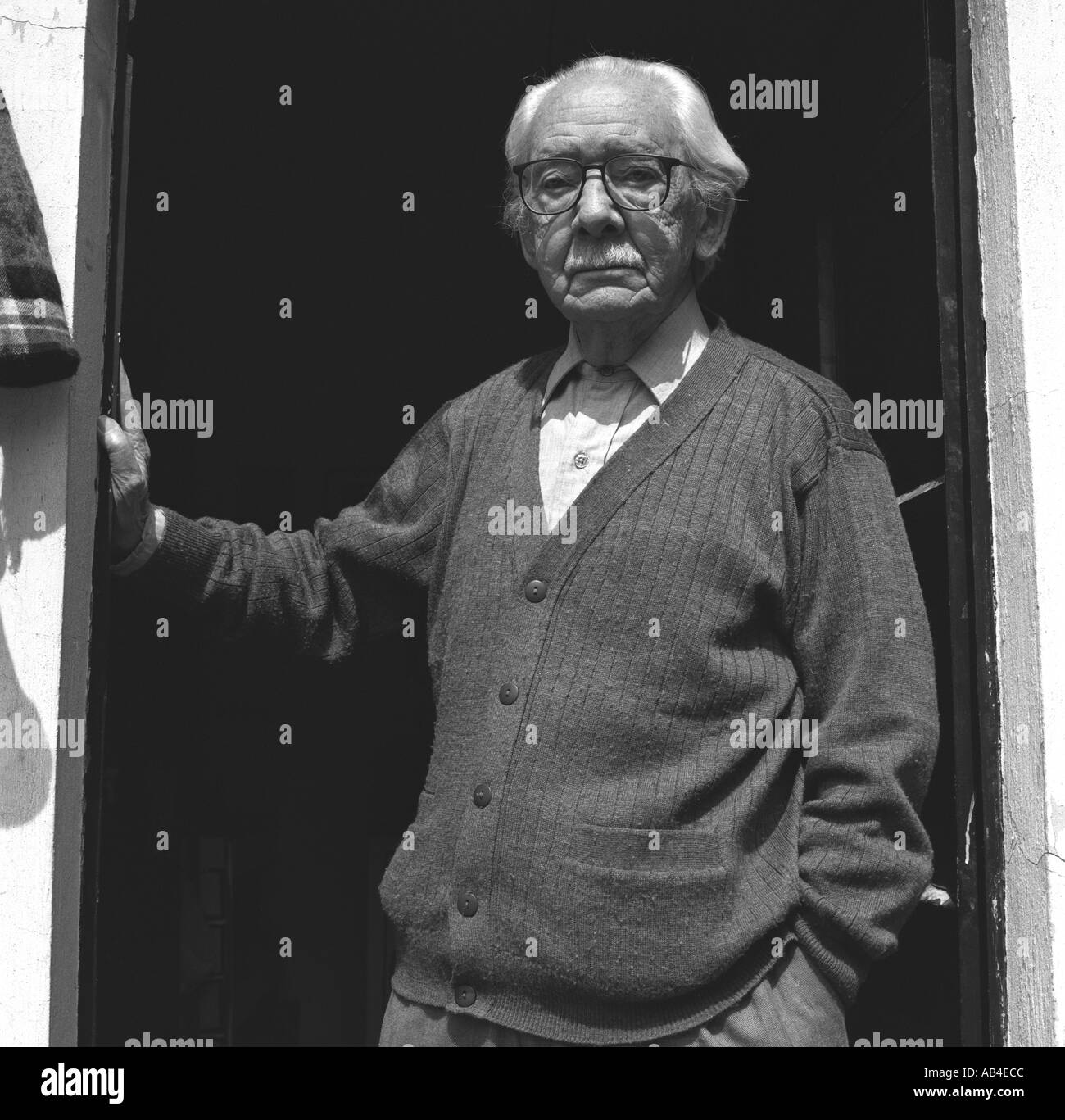

He continued to photograph well into his nineties, his curiosity undimmed. His later work maintained the same contemplative spirit, reflecting a lifetime of observing the world with a discerning eye. Manuel Álvarez Bravo passed away in 2002 at the remarkable age of 100, leaving behind an immense body of work that continues to captivate and challenge viewers.

In an age dominated by instant imagery and visual saturation, Álvarez Bravo’s photographs stand as a testament to the power of slow looking, of patience, and of finding the extraordinary in the ordinary. His "silent gaze" invites us to pause, to reflect, and to discover the hidden narratives and poetic truths that lie just beneath the surface of reality. Through his lens, Mexico, with all its beauty, pain, and mystery, comes alive, not as a mere backdrop, but as a living, breathing entity, seen and felt through the eyes of one of its most profound and enduring artists. His images are not just windows to the past; they are timeless reflections on the human condition, continuing to provoke thought and stir the imagination, ensuring his place as one of the true masters of the photographic medium.