A Scar on the Land: The Enduring Struggle at Akwesasne’s Border

Few places on the North American continent embody the complex, often fraught, relationship between Indigenous sovereignty, national borders, and the daily realities of life quite like Akwesasne. This Mohawk Nation territory, nestled along the picturesque St. Lawrence River, finds itself in the unique and unenviable position of being bisected by the international boundary between Canada and the United States, creating a persistent crucible of jurisdictional disputes, cultural challenges, and illicit activities. For the Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk people), the border is not merely a line on a map; it is a scar across their ancestral lands, their community, and their very identity.

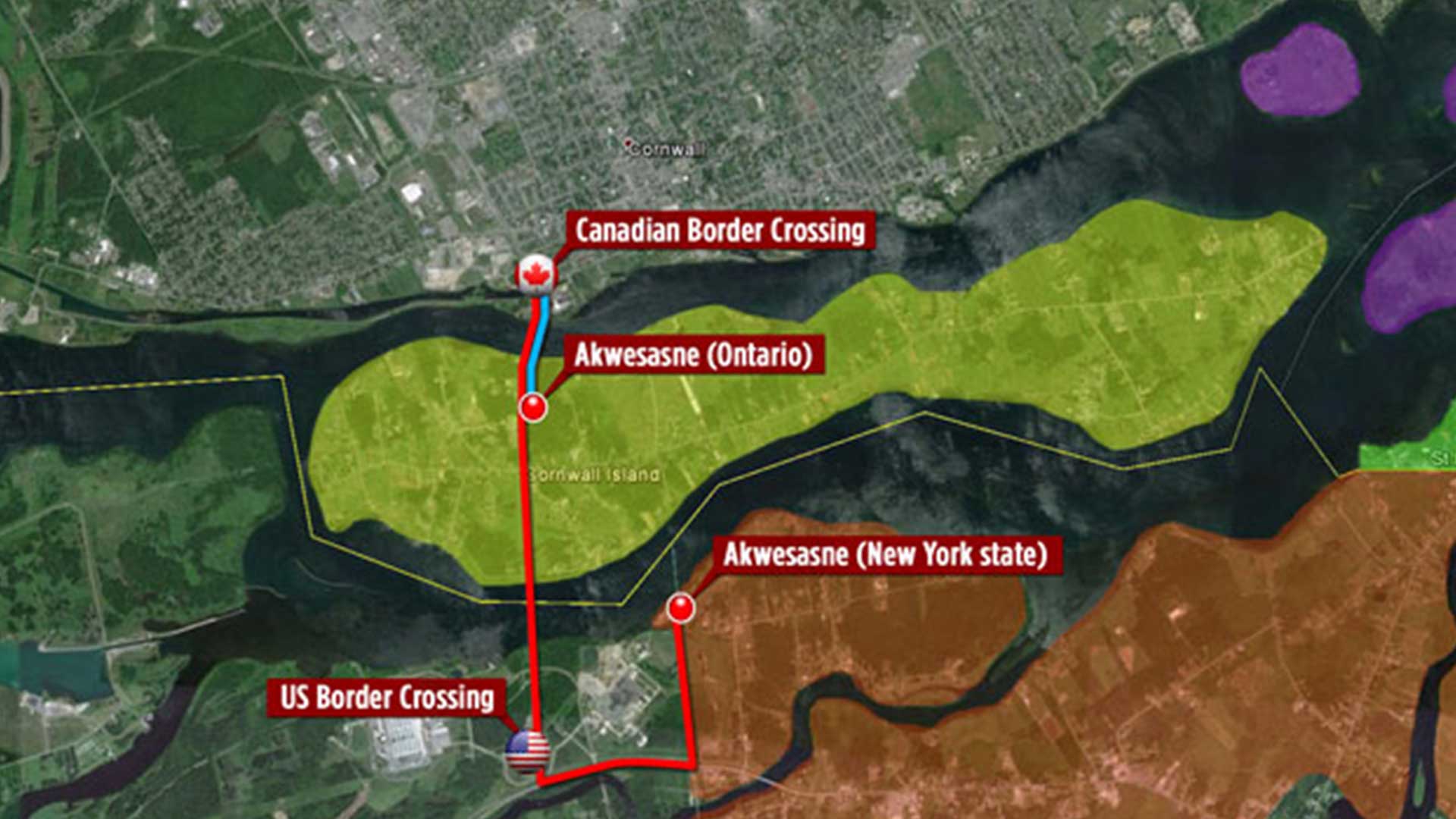

The geographical reality of Akwesasne is striking. Its lands straddle Quebec and Ontario in Canada, and New York State in the U.S. Crucially, a significant portion of the community resides on Cornwall Island, an island in the St. Lawrence River that sits directly in the path of the border. This unique topography, combined with the historical and legal complexities of Indigenous rights, has transformed Akwesasne into a flashpoint for issues ranging from the practicalities of daily commuting to high-stakes international smuggling.

A History of Imposed Lines

To understand the current predicament, one must look back to a time before these lines were drawn. For millennia, the Mohawk Nation occupied and governed these lands. Their territories stretched across vast swathes of what is now the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada. The St. Lawrence River was not a barrier but a highway, connecting communities and serving as a vital source of sustenance and trade.

The arrival of European colonizers brought new concepts of land ownership and national boundaries. Treaties were signed, often misunderstood or outright violated, and eventually, the 1783 Treaty of Paris formally established the border between the nascent United States and British North America. This line, drawn by distant powers, sliced through the heart of Mohawk territory without consultation or consent.

A flicker of recognition for Indigenous rights came with the 1794 Jay Treaty between Great Britain and the United States. Article III of this treaty explicitly recognized the right of "the Indians dwelling on either side of the said boundary line freely to pass and repass by land or inland navigation, into the respective territories and countries of the two parties, on the ordinary navigation thereof, and freely to carry on trade and commerce with each other." This article remains a cornerstone of Indigenous claims to border-crossing rights, yet its interpretation and application have been a continuous source of contention.

For the people of Akwesasne, the border became a daily reality, a constant reminder of an external authority that disregards their inherent sovereignty. It means that children attending school, parents going to work, or families visiting relatives often have to cross an international border, sometimes multiple times a day, complete with customs checks and the potential for delays or scrutiny.

The Daily Grind and the Deeper Wound

Imagine living in a community where your neighbor, your family, or your school lies in a different country, a few hundred meters away. For Akwesasne residents, this is not a hypothetical. Access to healthcare, emergency services, and even a local grocery store can involve navigating border checkpoints. This constant interruption of daily life underscores the fundamental clash between imposed state lines and the organic flow of a contiguous community.

"This border cuts through our living room," a common refrain among Akwesasne residents, encapsulates the profound sense of fragmentation. The artificial division has not only created practical hurdles but has also had deep social and cultural impacts, making it harder to maintain community cohesion and traditional practices that span the entire territory.

Moreover, the border imposes a system of laws and regulations that often conflict with Mohawk Nation laws and governance structures. The Mohawk Council of Akwesasne (MCA) in Canada and the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe (SRMT) in the U.S. operate their own governments, police forces, and community services, often in parallel to—and sometimes in direct tension with—federal, provincial, and state authorities. This jurisdictional overlap is a breeding ground for disputes, particularly when it comes to law enforcement.

A Hotbed for Contraband: Geography, Sovereignty, and Smuggling

Perhaps the most visible and widely publicized aspect of Akwesasne’s border issues is its reputation as a major corridor for smuggling. The unique geography of the territory, with its intricate network of islands, channels, and secluded shorelines, makes it an ideal transit point for illicit goods. The St. Lawrence River, once a Mohawk highway, is now a watery conduit for criminal enterprises.

From drugs (cocaine, opioids, cannabis) and firearms to untaxed tobacco, alcohol, and even human trafficking, the flow of contraband through Akwesasne is a persistent challenge for Canadian and U.S. border agencies. The proximity to major urban centers like Montreal, Ottawa, Toronto, and Syracuse further enhances its strategic value for organized crime.

The issue is deeply intertwined with the question of sovereignty. Mohawk authorities assert their right to govern their territory and enforce their own laws. However, Canadian Border Services Agency (CBSA) and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers view their mandate as extending to the entire international border, regardless of Indigenous land claims. This creates a dangerous grey area where jurisdiction is fiercely contested.

Smugglers exploit this ambiguity, often moving goods quickly across the river or through remote areas of the territory, leveraging the difficulty of cross-border pursuit by law enforcement. A chase initiated by Canadian police, for instance, might be forced to end at the border, allowing suspects to escape into U.S. territory, and vice-versa. While agreements exist for cross-border cooperation, the practicalities are often complex and fraught with legal hurdles.

The Akwesasne Mohawk Police Service (AMPS) works diligently to combat smuggling within their jurisdiction, often collaborating with federal agencies. However, they also face the difficult task of balancing the community’s safety with upholding Mohawk sovereignty and addressing the root causes of why some community members might become involved in illicit activities, which can include economic hardship and a sense of disenfranchisement.

The 2009 Crisis: A Defining Moment

The inherent tensions at Akwesasne boiled over into a major crisis in 2009. For decades, Canadian border services operated a customs office on Cornwall Island. However, concerns about the safety of CBSA officers and their ability to carry firearms on what Akwesasne considered Mohawk territory led the agency to announce plans to relocate the office off the island, to the Canadian mainland.

This decision was met with fierce opposition from the Mohawk Nation. Akwesasne leaders viewed the relocation as a unilateral imposition, a further erosion of their sovereignty, and a practical nightmare. If the CBSA office moved, it would mean that Akwesasne residents on Cornwall Island, already Canadian citizens, would have to cross into the U.S. (where the CBP remained) and then back into Canada on the mainland to access their own country. This was seen as a profound violation of their rights and an absurd logistical burden.

In response, Akwesasne residents established a blockade, preventing CBSA officers from accessing the Cornwall Island checkpoint. This led to the complete closure of the border crossing on the island, forcing traffic to detour for hours or to use smaller, often illicit, routes. The situation escalated, with protests, standoffs, and intense negotiations.

For nearly two years, the Cornwall Island border crossing remained effectively closed, creating an unprecedented "border limbo." Akwesasne residents faced immense hardship, as essential services were disrupted, economic activity stalled, and the community felt increasingly isolated. The crisis highlighted the profound power imbalance and the critical need for genuine, respectful consultation with Indigenous nations on matters affecting their territories.

Eventually, a temporary solution was reached in 2011, establishing an interim Canadian inspection facility on the north side of Cornwall Island, just before the bridge to the mainland, allowing for a more streamlined process for residents. While it brought some relief, the underlying issues of sovereignty and control over their lands remained largely unresolved, a constant reminder of the fragility of such arrangements.

Towards a Respectful Future?

The issues at Akwesasne are a microcosm of the broader challenges facing Indigenous nations whose territories were carved up by colonial borders. They underscore the ongoing struggle for self-determination and the recognition of inherent rights.

Addressing these complexities requires more than just increased law enforcement or new infrastructure. It demands a fundamental shift in perspective from both the Canadian and U.S. governments—a move towards genuinely recognizing and respecting Mohawk sovereignty. This could involve:

- Bilateral Agreements: Developing formal, nation-to-nation agreements between the Mohawk Nation and Canada/U.S. that clearly define jurisdictional boundaries and establish protocols for cooperation, particularly in law enforcement and border management.

- Economic Development: Investing in sustainable economic opportunities within Akwesasne to reduce reliance on illicit economies and empower community members.

- Cultural Understanding: Fostering greater understanding among border agents and the public about Mohawk history, culture, and their unique relationship with the land and the border.

- Jay Treaty Implementation: Fully honoring the spirit and intent of the Jay Treaty, ensuring free passage and trade for Indigenous peoples across the border without undue hindrance.

The border at Akwesasne is more than a line; it is a living testament to a history of imposition and a present-day struggle for justice. While the challenges are immense, the resilience of the Mohawk Nation endures. Their continued assertion of sovereignty, their efforts to build a strong community, and their unwavering demand for respect serve as a powerful reminder that true reconciliation must extend to every corner of the land, especially those bisected by the artificial scars of history. The path forward for Akwesasne, and for similar Indigenous communities globally, lies in dialogue, mutual respect, and the recognition that the lines drawn on maps can never erase the deeper, more ancient connections to land and identity.