When Coalfields Bled: The Unforgotten Fury of the Paint Creek-Cabin Creek Strike

In the rugged heart of West Virginia, where mountains hold untold riches of coal and the air once thrummed with the ceaseless grind of industry, a different sound echoed over a century ago: the crackle of gunfire, the cries of the dispossessed, and the defiant roar of men and women fighting for their dignity. From the spring of 1912 through the summer of 1913, the remote valleys of Paint Creek and Cabin Creek became the epicenter of one of America’s most brutal and pivotal labor conflicts – a struggle that pitted desperate miners against powerful coal operators, private armies, and eventually, the state itself. This was the Paint Creek-Cabin Creek Strike, a crucible of violence and determination that forged the future of labor rights in the nation.

The Seeds of Discontent: Industrial Feudalism

To understand the ferocity of the Paint Creek-Cabin Creek strike, one must first grasp the conditions that preceded it. The early 20th century coalfields of southern West Virginia were, for many miners, a landscape of "industrial feudalism." Companies owned everything: the mines, the houses, the stores, even the churches and schools. Miners were paid in scrip, redeemable only at company stores where prices were often inflated, trapping them in a cycle of debt. Wages were meager, hours long, and the work itself incredibly dangerous, with little regard for safety.

Perhaps most galling was the absence of a checkweighman – an independent, union-appointed employee responsible for ensuring miners were accurately paid for the coal they extracted. Without one, operators could shortchange miners with impunity, often by designating good coal as "slack" (fine coal dust) for which they paid less. "The companies cheated them on the weight," explained one historian, "they cheated them in the company store, and they housed them in miserable shacks."

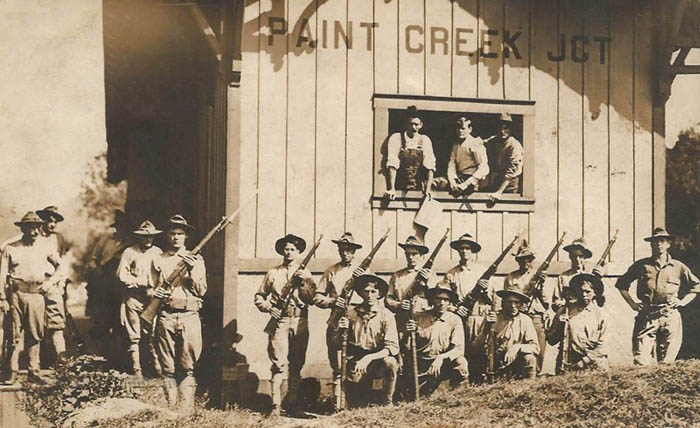

Adding to this oppressive atmosphere was the pervasive fear instilled by private mine guards, often deputized by the state or hired from notorious detective agencies like the Baldwin-Felts. These "gun thugs," as miners called them, enforced company rules with an iron fist, preventing union organizers from even setting foot on company property and squashing any hint of dissent. They were, in essence, a private army designed to keep labor cheap and docile.

The Call to Arms: The UMWA and the Operators’ Resistance

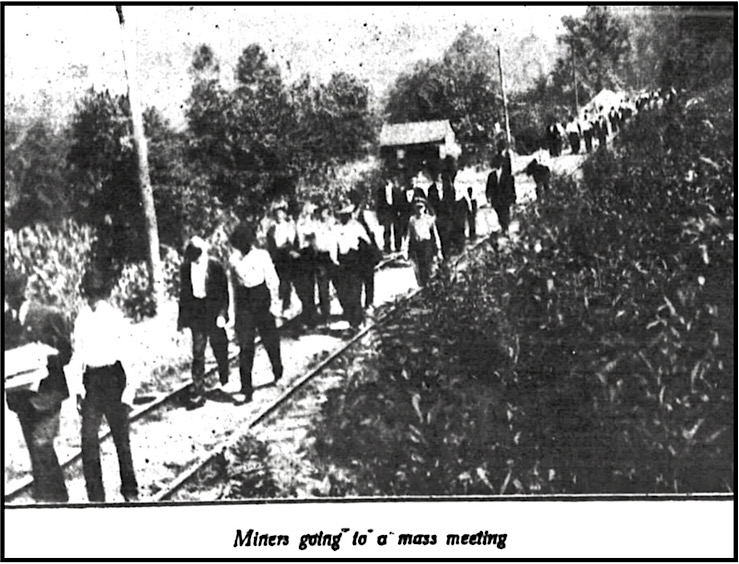

By 1912, the miners of Paint Creek and Cabin Creek had endured enough. They were earning significantly less than their counterparts in other unionized fields, and their demands were clear: an increase in wages, the right to an independent checkweighman, and crucially, recognition of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) as their bargaining agent. The UMWA, led by its fiery and charismatic organizer, Mary Harris "Mother" Jones, had been making inroads in the region, promising hope and solidarity.

On April 1, 1912, when the Kanawha Coal Operators Association refused to meet their demands, approximately 7,500 miners across the two creeks laid down their tools. The strike was on.

The operators’ response was immediate and brutal. Miners and their families were summarily evicted from company housing. With nowhere else to go, the UMWA quickly established tent colonies on private land along the creeks, providing shelter and sustenance for the thousands now living in destitution. These tent cities became beacons of defiance, but also vulnerable targets.

The operators, unwilling to concede, doubled down on their security. Baldwin-Felts agents, led by the notorious brothers Thomas and Albert Felts, poured into the region, armed with high-powered rifles and a license to intimidate. Their mission: break the strike by any means necessary. They hired scabs, imported from other states, to work the mines, further inflaming tensions.

Escalation to Open Warfare: The Battle of Holly Grove and the "Bull Moose Special"

What began as a labor dispute quickly devolved into open warfare. Skirmishes between striking miners and Baldwin-Felts guards became commonplace. Snipers took positions on hillsides, exchanging fire across the narrow valleys. The peaceful existence of the tent colonies was shattered by the constant threat of violence.

One of the most infamous incidents occurred on July 26, 1912. Guards, stationed in a machine-gun equipped fortress known as "Bullmoose" (or "Bull Moose") Hall at Mucklow, opened fire on the Holly Grove tent colony, killing two miners and wounding others. This unprovoked attack further radicalized the miners, pushing them from defensive postures to retaliatory action.

The ultimate symbol of corporate brutality arrived in the form of the "Bull Moose Special." This was a C&O passenger train, heavily armored with steel plating, outfitted with a searchlight, and mounted with Gatling guns and automatic rifles. On the night of February 7, 1913, the "Bull Moose Special," carrying Baldwin-Felts guards, steamed through the Paint Creek valley, riddling the tent colony at Holly Grove with hundreds of rounds of ammunition. The terrifying spectacle left at least one miner dead and several wounded, including women and children. It was an act of terror, a clear message from the operators: resistance would be met with overwhelming force.

Mother Jones and the Reign of Martial Law

Throughout this escalating conflict, the indomitable figure of Mother Jones, then in her early 80s, was a constant presence. She traversed the creeks, rallying miners with her fiery speeches, organizing women and children to participate in protests, and defying the armed guards at every turn. "Pray for the dead and fight like hell for the living!" she famously exhorted the miners. Her courage inspired thousands, but also made her a prime target.

As the violence spiraled, newly elected Governor William E. Glasscock struggled to maintain order. His successor, Governor Henry D. Hatfield, took office in March 1913, inheriting a war zone. Hatfield, a physician and Republican, initially attempted to mediate, but facing continued bloodshed and the operators’ intransigence, he declared martial law on March 15, 1913.

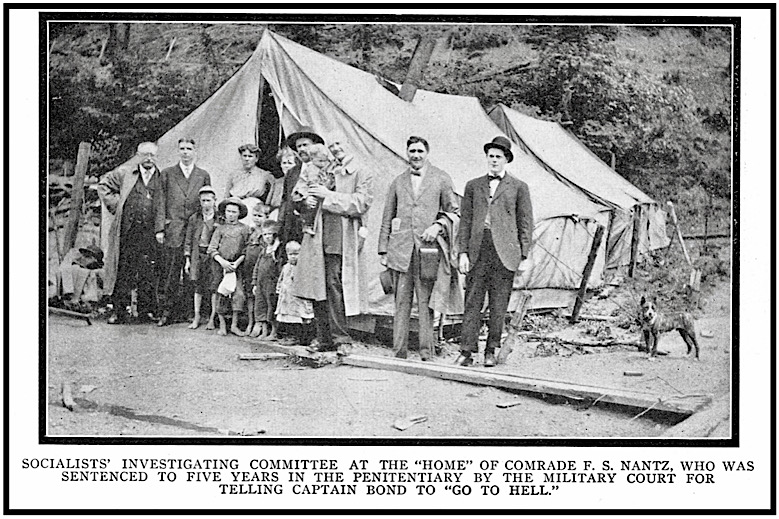

The imposition of martial law was swift and draconian. State militia poured into the region, disarming both miners and guards, though critics argued the disarming was far more thorough on the miners’ side. Hundreds of miners, including Mother Jones, were arrested and tried by military courts, denying them their constitutional rights to trial by jury. Mother Jones, charged with conspiracy to commit murder, was held in a military hospital under guard, her "crime" being her unwavering support for the striking workers. Her arrest and subsequent military trial sparked national outrage, bringing the plight of the West Virginia miners to the forefront of the American consciousness.

A Tenuous Resolution and Lasting Legacy

Under the intense pressure of martial law and national scrutiny, Governor Hatfield eventually forced a "settlement." On April 25, 1913, he brokered a deal that, while not a complete victory for the UMWA, represented significant concessions from the operators. The agreement included a nine-hour workday, the right to an independent checkweighman (a major victory), and a modest wage increase. Crucially, the hated Baldwin-Felts guards were to be removed from the creeks, replaced by state police. However, full union recognition remained elusive, and the "yellow-dog contracts" (which forced miners to agree not to join a union as a condition of employment) were not abolished. Many arrested miners, including Mother Jones, remained imprisoned until the martial law was finally lifted in June 1913.

The Paint Creek-Cabin Creek Strike had a profound, if complex, legacy. It was a bloody and costly conflict, claiming an estimated 50 to 200 lives (the exact number is still debated due to unrecorded deaths and disappearances). It exposed the raw power dynamics of industrial America and the lengths to which corporations would go to suppress labor. It highlighted the critical role of charismatic figures like Mother Jones and the importance of national media attention in swaying public opinion.

While the UMWA did not achieve full recognition in the Kanawha coalfields immediately, the strike laid crucial groundwork. The partial victories energized the union and provided a blueprint for future organizing efforts. It served as a precursor to the larger and even more violent West Virginia Mine Wars of the 1920s, culminating in the Battle of Blair Mountain, where thousands of armed miners clashed with state militia and private forces. The brutality of Paint Creek-Cabin Creek shocked the nation and contributed to a growing movement for labor reform and the protection of workers’ rights.

The valleys of Paint Creek and Cabin Creek, once scarred by bullets and stained with blood, now appear tranquil. But the echoes of that fierce struggle, the memory of those who fought for a better life, and the enduring lessons of their courage resonate still. The Paint Creek-Cabin Creek Strike stands as a stark reminder of the sacrifices made in the long, arduous fight for industrial justice, a testament to the indomitable spirit of ordinary people confronting extraordinary oppression. It is a chapter in American history that, though often overlooked, continues to shape our understanding of labor, power, and the cost of human dignity.