Beneath the Black Gold: West Virginia’s Enduring Scars of Coal Mine Disasters

In the rugged, verdant embrace of the Appalachian Mountains, where the hills roll like an endless ocean of green, lies a history etched in the very rock beneath. This is West Virginia, a state whose identity is inextricably bound to coal – a black diamond that has simultaneously brought prosperity and unimaginable tragedy. For generations, the promise of the seam has lured men into the earth’s dark maw, a perilous dance between life and death that has repeatedly left deep, unhealing scars on communities and families. The story of West Virginia coal disasters is not just a chronicle of explosions, cave-ins, and methane pockets; it is a profound testament to human resilience, corporate negligence, regulatory evolution, and the enduring, often brutal, cost of progress.

Coal, in West Virginia, is more than just a commodity; it’s a way of life, a cultural cornerstone, and a source of both immense pride and profound sorrow. From the state’s earliest days, its rich coal seams fueled the nation’s industrial revolution, powering factories, heating homes, and shaping the very landscape. But this vital energy source came at a steep price. The early 20th century, in particular, was a grim era for coal miners, a time when safety regulations were virtually non-existent, and the lives of those who extracted the black gold were considered expendable in the relentless pursuit of profit.

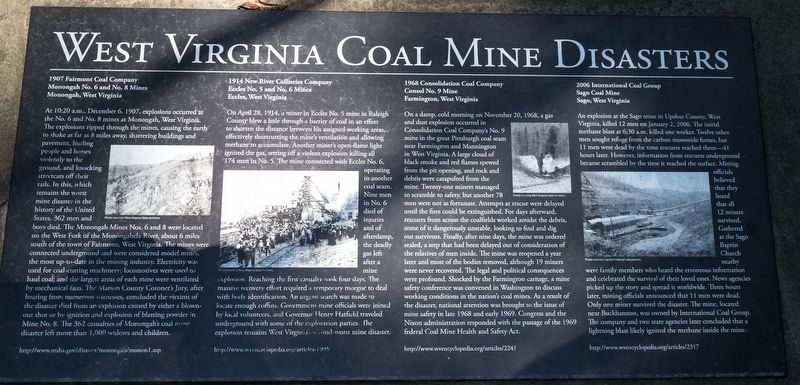

Monongah, 1907: The Genesis of Horror

No discussion of West Virginia coal disasters can begin without acknowledging the catastrophe that remains the deadliest industrial accident in American history: the Monongah Mine Disaster of December 6, 1907. In the twin mines of Monongah, Marion County, an explosion ripped through the shafts, trapping and killing an official count of 362 men. The true toll, however, is believed to be significantly higher, perhaps closer to 500, as many immigrant laborers – Italians, Slavs, Poles – were often unregistered.

The disaster was a horrific confluence of inadequate ventilation, rampant coal dust, and a blatant disregard for safety. Miners often worked in conditions ripe for disaster, with open flame lamps igniting volatile methane gas. The Monongah explosion was so powerful it shook the ground for miles, collapsing shafts and sealing off any hope for those deep within. The aftermath was a scene of utter devastation: a community shattered, families wiped out, and the stark realization that the lives of miners were shockingly undervalued. The Monongah tragedy, while horrific, served as a grim catalyst, stirring a nascent public consciousness and laying the groundwork for the eventual creation of the U.S. Bureau of Mines in 1910, marking the first tentative steps towards federal oversight of mine safety.

Farmington, 1968: A Call for Change

Decades later, despite technological advancements and a growing awareness of safety, the inherent dangers of mining remained. On November 20, 1968, another devastating explosion rocked the Consol No. 9 mine in Farmington, Marion County. Seventy-eight men were trapped more than a mile deep, engulfed by flames and toxic gases. For nine agonizing days, the nation watched as rescue efforts unfolded, a desperate struggle against impossible odds. Ultimately, none of the trapped miners survived.

The Farmington disaster sent shockwaves through the country. It exposed the stark reality that even with existing state laws, enforcement was often lax, and the pursuit of production frequently trumped safety concerns. The public outcry was immense, fueled by heart-wrenching images of grieving families and the somber realization that such a tragedy could still occur. This disaster became a pivotal moment, providing the impetus for the landmark Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969. This comprehensive legislation dramatically increased federal oversight, established mandatory safety standards, introduced regular inspections, and gave miners unprecedented rights, including the ability to report unsafe conditions without fear of reprisal. As one miner’s widow, Martha Jones, famously said, "Something good has to come from this." And indeed, it did, ushering in an era of significantly improved mine safety, though far from perfect.

Sago, 2006: A Cruel Echo of Hope and Despair

Even with robust federal regulations and the vigilance of the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA), the mountains still hold their secrets and their dangers. The Sago Mine Disaster in Upshur County on January 2, 2006, served as a stark, painful reminder that the battle for safety is never truly won. An explosion, likely caused by a lightning strike igniting methane, trapped 13 miners deep underground.

What followed was a harrowing 41-hour ordeal that captivated the nation and illustrated the raw emotional rollercoaster of a mine rescue. Initial, erroneous reports of 12 survivors sparked jubilation, only to be tragically corrected hours later: 12 men had died, leaving only one survivor, Randal McCloy Jr., who suffered severe injuries. The Sago disaster highlighted critical communication failures, the limitations of existing rescue technology, and the psychological toll on communities that cling to every whisper of hope. It led to further legislative scrutiny and increased calls for improvements in emergency communication systems, refuge chambers, and the training of rescue teams. "We thought we had them all," recalled a local pastor, encapsulating the profound heartbreak of the community’s brief moment of joy turning to ashes.

Upper Big Branch, 2010: Corporate Greed and Systemic Failure

Just four years after Sago, West Virginia was plunged into mourning once more, this time by a disaster that, for many, epitomized the insidious combination of corporate negligence and regulatory laxity. On April 5, 2010, an explosion at Massey Energy’s Upper Big Branch (UBB) mine in Raleigh County killed 29 miners, making it the worst U.S. coal mining disaster in 40 years.

Investigations into UBB revealed a horrifying picture of systemic safety violations. MSHA cited Massey Energy for hundreds of violations in the months leading up to the explosion, many related to ventilation, methane control, and the accumulation of combustible coal dust – the very conditions that caused the explosion. Miners testified to a culture where production goals were prioritized over safety, where managers allegedly warned miners of upcoming inspections, and where safety complaints were often ignored or punished.

The official report by an independent investigative panel concluded unequivocally: "The Upper Big Branch Mine disaster was not a natural catastrophe. It was a man-made catastrophe, resulting from systematic, intentional, and aggressive efforts by Massey Energy to put production ahead of safety." This damning conclusion led to criminal charges against several Massey executives, including former CEO Don Blankenship, who was convicted of a misdemeanor conspiracy to violate mine safety standards. The UBB disaster ripped open the debate about corporate accountability, the effectiveness of MSHA’s enforcement powers, and the desperate need for a culture shift within the industry. It was a stark, brutal reminder that even with laws on the books, their effectiveness hinges on vigilant enforcement and ethical leadership.

The Enduring Legacy and Ongoing Struggle

The scars left by Monongah, Farmington, Sago, and Upper Big Branch are not merely historical footnotes; they are woven into the fabric of West Virginia’s identity. These disasters have shaped its laws, its culture, and the very psyche of its people. Each tragedy has spurred reforms, yet the battle for absolute safety remains an ongoing struggle.

Today, coal mining in West Virginia continues, albeit on a smaller scale than in its heyday. The industry faces new challenges from environmental concerns and a shift towards renewable energy sources. Yet, for those who still work beneath the earth, the inherent dangers persist. Modern mines are equipped with advanced safety technologies: sophisticated methane detectors, reinforced roofs, elaborate ventilation systems, and self-contained breathing apparatuses. Rescue teams are better trained and equipped. MSHA, though often criticized for its enforcement, continues its vital mission of inspection and regulation.

However, the human element remains paramount. The decisions made by mining companies regarding investment in safety, the vigilance of regulatory bodies, and the courage of miners to speak up about unsafe conditions are all critical factors. The spirit of West Virginia, forged in the crucible of these disasters, is one of resilience and remembrance. Memorials dot the landscape, honoring the fallen and serving as poignant reminders of the sacrifices made.

As the sun sets over the Appalachian peaks, casting long shadows across the valleys, the memory of those lost in the mines endures. The deep scars of the mountain are a permanent testament to the cost of extracting black gold, a solemn promise that the lessons learned through tears and tragedy must never be forgotten. The story of West Virginia’s coal disasters is a powerful narrative of human vulnerability and unwavering spirit, a continuous plea for vigilance in the face of an industry that demands the ultimate respect for the lives it touches.