The Crucible of Civilization: Unearthing the Transformative Power of the Archaic Period

Often overshadowed by the dazzling achievements of Classical Greece, the Archaic Period (roughly 800-480 BCE) was, in fact, the vibrant crucible in which the fundamental elements of Western civilization were forged. It was an era of unprecedented transformation, a dynamic bridge spanning the shadowy Dark Ages and the golden age of Pericles, laying the essential groundwork for everything from democracy and philosophy to epic poetry and monumental art. To overlook this period is to miss the very genesis of the ideas and institutions that continue to shape our world.

This wasn’t a static prelude but a whirlwind of innovation, expansion, and profound social restructuring. From the emergence of the polis – the iconic Greek city-state – to the birth of the alphabet, the codification of laws, and the first stirrings of systematic philosophical inquiry, the Archaic Period was a relentless engine of change.

Emerging from the Shadows: The Birth of the Polis

.jpg)

Following the collapse of the Mycenaean civilization around 1200 BCE, Greece entered a period often referred to as the "Dark Ages." Literacy vanished, trade dwindled, and populations plummeted. But by the 8th century BCE, faint flickers of recovery began to emerge, coalescing into what would become the defining political and social unit of ancient Greece: the polis.

The polis was far more than just a city; it was a unique concept embodying a self-governing community of citizens, bound by shared laws, customs, and a collective identity. Unlike the vast empires of the Near East, where subjects owed fealty to a distant king, the polis fostered a sense of civic participation and responsibility. As historian M.I. Finley aptly noted, "The Greek polis was a community of citizens, and citizenship involved direct participation in public life." This radical idea of shared governance, even if initially limited to a land-owning aristocracy, was a profound departure from earlier political models and the very bedrock upon which later democratic ideals would be built.

The growth of the polis was driven by a resurgent population and a need for organized defense and administration. Villages clustered around fortified acropolises or natural strongholds, gradually developing distinct political identities. Athens, Sparta, Corinth, and Thebes were among the hundreds of such independent entities that dotted the Hellenic landscape, each a laboratory for political experimentation.

The Age of Expansion: Hellenic Horizons Broaden

As the poleis grew, so too did their populations, often outstripping the capacity of local agricultural land to sustain them. This economic pressure, coupled with internal political strife and a burgeoning spirit of adventure, propelled the Greeks into an extraordinary period of colonization from the mid-8th to the mid-6th centuries BCE.

Greek settlers, often with the blessing of the Delphic Oracle, embarked on perilous voyages across the Mediterranean and Black Seas, establishing new poleis from the coasts of modern-day Spain to the shores of Ukraine. Sicily and Southern Italy, rich in fertile land, became known as Magna Graecia (Great Greece), boasting cities like Syracuse and Sybaris that rivaled the wealth of their mother cities.

This wave of colonization had far-reaching consequences. It eased population pressures, stimulated trade, and spread Greek culture, language, and institutions across a vast geographical area. It also brought the Greeks into direct contact with diverse peoples – Phoenicians, Egyptians, Etruscans – fostering a sense of shared Hellenic identity that transcended individual polis loyalties. The very act of establishing a colony required sophisticated organization and forethought, honing the political and logistical skills that would prove crucial in later conflicts.

Economic and Social Revolutions: From Aristocrats to Hoplites

The Archaic Period witnessed dramatic shifts in the economic and social fabric of Greek society. The expansion of trade, particularly maritime trade, created new avenues for wealth generation, challenging the traditional dominance of the land-owning aristocracy. Pottery, olive oil, wine, and metalwork were exchanged for grain, timber, and other raw materials, enriching a rising class of merchants and artisans.

A pivotal innovation of this era was the introduction of coinage, likely adopted from the Lydians in the 7th century BCE. This standardized medium of exchange revolutionized commerce, making transactions more efficient and further stimulating economic growth. No longer reliant on cumbersome barter, merchants could amass and deploy capital with unprecedented ease, accelerating the pace of economic development.

Perhaps even more profound was the "Hoplite Revolution." The hoplite was a heavily armed infantryman, equipped with a large round shield (hoplon), spear, and sword, fighting in a tightly packed formation called the phalanx. This new style of warfare, which emphasized discipline, cohesion, and collective strength over individual aristocratic prowess, democratized military service. Middle-class citizens, who could afford their own armor, became the backbone of the polis‘s defense.

This military transformation had significant political repercussions. Citizens who risked their lives for the polis began to demand a greater say in its governance. The old aristocratic monopoly on power started to crack under the weight of these new social realities, paving the way for political reforms.

Political Experimentation: Tyrants, Lawgivers, and the Seeds of Democracy

The internal dynamics of the Archaic poleis were often tumultuous. The struggle between the entrenched aristocracy and the emerging classes (merchants, hoplites, and the poor) frequently led to social unrest. Into this volatile environment stepped the tyrants.

Tyranny in the Archaic sense was not necessarily oppressive in its early forms. Tyrants were often charismatic strongmen who seized power, typically with popular support, by promising to break the power of the aristocrats and enact reforms benefiting the common people. Figures like Peisistratos in Athens, for example, invested in public works, supported the arts, and distributed land to the poor. However, their rule was by definition extra-constitutional, and as their power consolidated, many became autocratic and oppressive, leading to their eventual overthrow.

The push for political stability also saw the rise of lawgivers. The legendary figure of Draco in Athens (c. 621 BCE) is famous for his exceedingly harsh legal code, where almost all offenses were punishable by death – giving us the term "draconian." While brutal, it was a crucial step: it meant that laws were now written down and publicly known, providing a degree of consistency and impartiality previously absent.

A far more significant figure was Solon, an Athenian aristocrat and poet, who was appointed archon with special powers in 594 BCE. Solon’s reforms were a watershed moment. He famously abolished debt slavery, preventing citizens from being enslaved for their debts – a radical move that protected the autonomy of the individual. He also reorganized Athenian society into four property classes, granting political rights based on wealth rather than birth, and established a popular assembly (the ekklesia) and a council (the boule). While not full democracy, Solon’s reforms moved Athens decisively towards broader civic participation.

The final push towards Athenian democracy came with Cleisthenes at the end of the Archaic Period (508/507 BCE). He fundamentally reorganized the citizen body, breaking the power of traditional aristocratic clans and creating new administrative units (demoi and tribes) that fostered local loyalties and integrated citizens from across Attica. Cleisthenes is rightly considered the "father of Athenian democracy," laying the institutional framework for the radical self-governance that would flourish in the Classical era.

Meanwhile, other poleis pursued different paths. Sparta, for instance, developed a unique and rigid military oligarchy, with a highly disciplined citizen army and a society geared entirely towards military readiness, a stark contrast to Athens’ evolving democratic ideals.

A Cultural Renaissance: Art, Literature, and Thought Awaken

The Archaic Period was also a time of breathtaking cultural flourishing, a reawakening after the intellectual dormancy of the Dark Ages.

One of the most profound developments was the adoption of the Phoenician alphabet, adapted by the Greeks to include vowels around 800 BCE. This invention was revolutionary; it simplified writing, making literacy accessible to a wider segment of the population and thus democratizing knowledge in a way never before seen. It facilitated the recording of laws, treaties, and, crucially, literature.

The greatest literary achievements of the early Archaic Period were the epic poems of Homer, the Iliad and the Odyssey. Though their exact dating is debated, they are firmly rooted in this era and served as a foundational text for Greek identity, morality, and history. They were not merely stories but cultural touchstones, recited and revered, shaping the Greek worldview for centuries to come.

Beyond Homer, the Archaic Period saw the rise of lyric poetry, a more personal and introspective form. Poets like Sappho of Lesbos, the "Tenth Muse," explored themes of love, desire, and the individual experience with exquisite beauty. Archilochus of Paros, another influential lyric poet, was known for his biting wit and candid expressions of personal frustration and defiance. These poets moved beyond the grand narratives of epic, offering a glimpse into the diverse emotional landscape of the time.

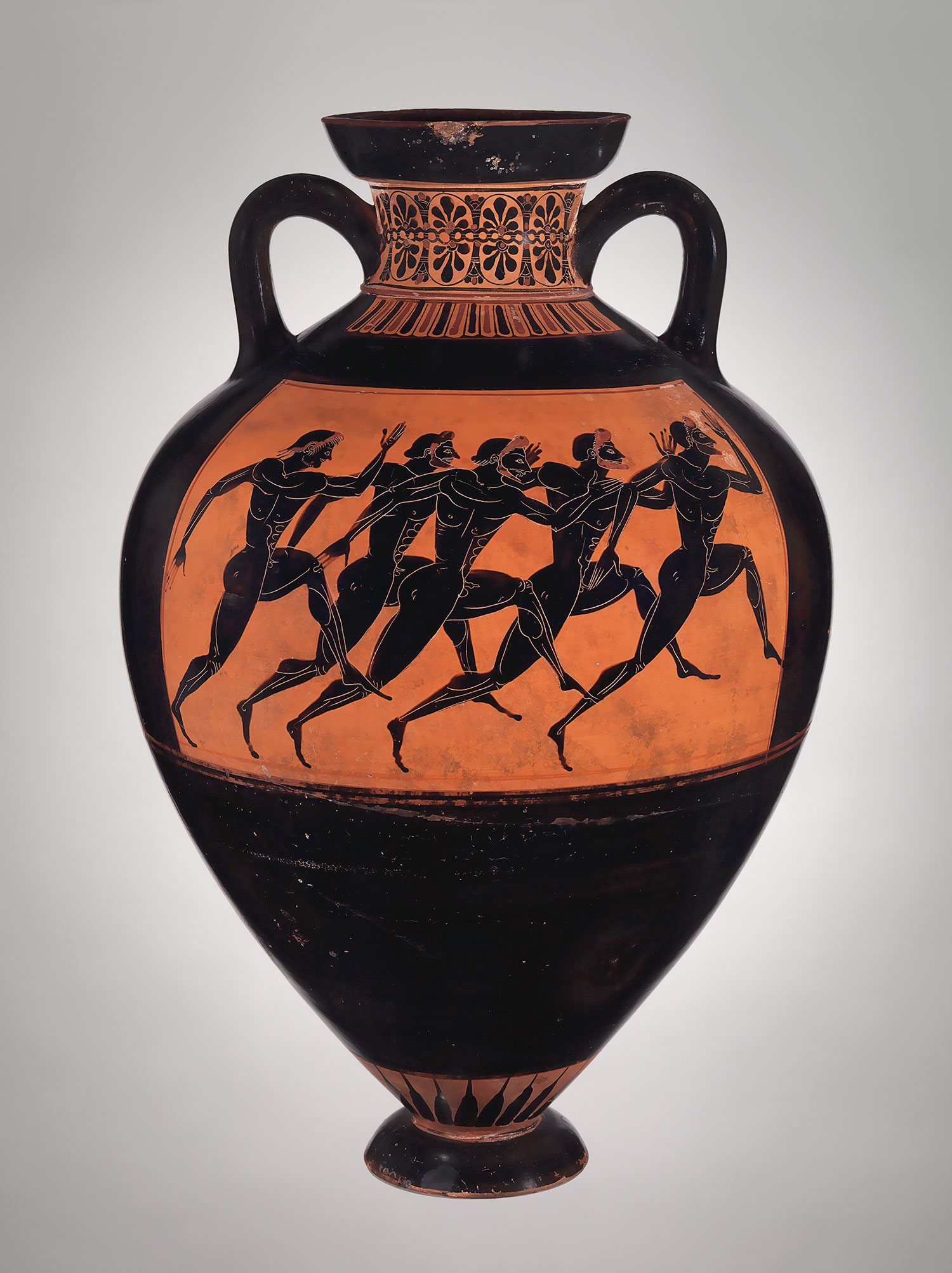

In art, the Archaic Period witnessed a stylistic evolution from the abstract geometric patterns of the Dark Ages to increasingly naturalistic representations. Sculpture, influenced by Egyptian models, produced the iconic kouros (nude male youth) and kore (draped female maiden) figures. While initially stiff and frontal, these statues gradually incorporated more lifelike features and a sense of movement, culminating in the "Archaic smile" – a subtle, enigmatic expression that hints at the burgeoning realism of later periods. Architecture also developed, with the first monumental stone temples being constructed, setting the stage for the classical orders (Doric and Ionic).

Finally, the Archaic Period saw the birth of Western philosophy. In the bustling Ionian cities of Asia Minor, thinkers like Thales of Miletus began to question the mythical explanations of the world, seeking rational, natural causes for phenomena. Thales’ proposition that water was the fundamental substance of the universe, while perhaps incorrect, marked a radical shift from myth to reason, laying the groundwork for scientific inquiry and abstract thought. Other Presocratic philosophers like Anaximander, Anaximenes, and Pythagoras followed, grappling with fundamental questions about existence, cosmology, and mathematics.

Panhellenic institutions also solidified during this time, fostering a shared sense of Greekness. The Olympic Games, traditionally dated to 776 BCE, brought together athletes from across the Greek world in a spirit of competition and shared religious observance. The Oracle at Delphi became a revered panhellenic sanctuary, its pronouncements guiding poleis on matters of war, colonization, and law.

The Looming Storm and the End of an Era

As the Archaic Period drew to a close, the nascent Greek world, vibrant and dynamic, found itself on the brink of its greatest challenge: the looming threat of the mighty Persian Empire. The Ionian Revolt (499-493 BCE), in which Greek cities in Asia Minor rebelled against Persian rule, drew mainland Greece into a conflict that would define its future.

The Persian Wars (499-449 BCE), beginning with the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE and culminating in the epic struggles of Thermopylae, Salamis, and Plataea in 480-479 BCE, marked the definitive end of the Archaic Period. The unified resistance of the Greek poleis against the seemingly invincible Persian Empire forged a new level of panhellenic identity and pride. It was a test of the very foundations laid during the preceding centuries – the civic participation of the polis, the military prowess of the hoplite phalanx, and the cultural cohesion fostered by shared language and religion.

Legacy of a Formative Age

The Archaic Period, therefore, was far more than a mere transition. It was an age of profound and often turbulent creation, where the seeds of democracy, philosophy, literature, and art were sown and nurtured. It was the era that gave us the polis, the alphabet, Homer, the first glimmerings of rational thought, and the very concept of the citizen-soldier. Without the crucible of the Archaic Period, the classical wonders of Athens and Sparta, the intellectual brilliance of Plato and Aristotle, and the architectural marvels of the Parthenon would simply not have been possible.

Its legacy echoes down the millennia, a testament to the transformative power of human ingenuity and resilience. The Archaic Period reminds us that the grand narratives of civilization are often built not in sudden explosions of genius, but in the painstaking, often messy, and always dynamic process of experimentation and evolution. It was, truly, where the future of the Western world began.