The Ghost of Rufus Buck: Indian Territory’s Violent Dream of a Republic

In the twilight years of the 19th century, as the American frontier began to shrink and the myth of the "Wild West" gave way to the realities of an encroaching modern world, a chilling chapter unfolded in the heart of Indian Territory. It was a story etched in blood and desperation, led by a young Creek man named Rufus Buck, whose brief but brutal reign as an outlaw carved his name into the annals of a vanishing era. More than just a tale of frontier lawlessness, the saga of the Rufus Buck Gang is a dark mirror reflecting the racial tensions, land disputes, and cultural clashes that defined the twilight of indigenous sovereignty in what would soon become Oklahoma.

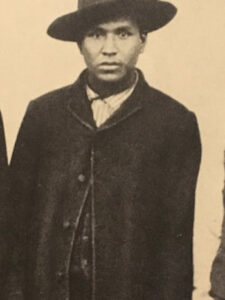

Rufus Buck was a mixed-blood Creek, born around 1872 into a world teetering on the precipice of profound change. Indian Territory, a vast expanse set aside for the Five Civilized Tribes – Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole – was far from the peaceful sanctuary envisioned. It was a land of fractured sovereignty, where tribal laws struggled to assert authority against a rising tide of white settlers, federal marshals, and a burgeoning criminal element. The Dawes Act of 1887, which aimed to break up communal tribal lands into individual allotments, fueled deep resentment and fear among many Native Americans, who saw it as a thinly veiled land grab and an existential threat to their way of life.

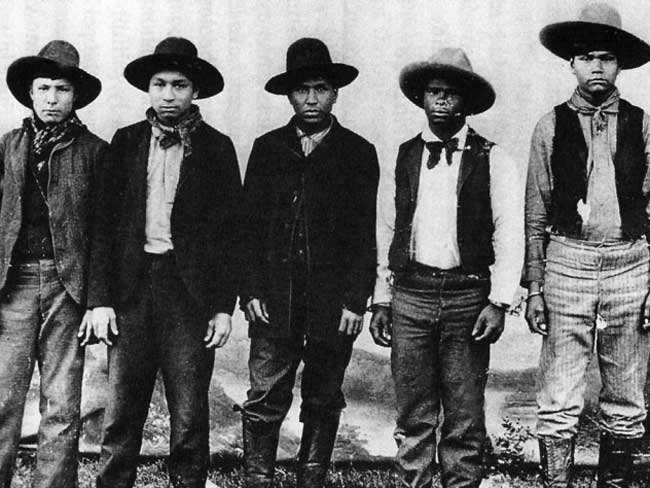

It was in this crucible of fear, anger, and lawlessness that Rufus Buck, barely out of his teens, began to assemble his notorious gang. His companions were equally young, equally desperate, and shared his mixed heritage: Lewis Davis, Sam Sampson, Maoma July, and Lucky Davis. They were a product of their volatile environment, young men caught between two worlds, struggling for identity and agency in a land where their ancestral rights were rapidly eroding. Some historians suggest their motivations were rooted in a fierce, if misguided, desire to resist the white encroachment and reclaim a sense of autonomy for their people.

The gang’s infamous crime spree ignited in the summer of 1895, a terrifying whirlwind of robbery, murder, and unspeakable violence that sent shockwaves across Indian Territory and into the neighboring states. Their initial targets were typical of frontier outlaws: isolated stores, post offices, and lone travelers. They robbed the store of a man named Gus Storey, killing him in cold blood, a crime that would later seal their fate. But the Rufus Buck Gang harbored ambitions far grander and more terrifying than mere banditry.

According to contemporary accounts and later historical analysis, Rufus Buck envisioned something akin to an "Indian Republic." Their plan, audacious and naive in equal measure, was to seize control of parts of Indian Territory, rallying other disaffected Native Americans to their cause, and driving out the white settlers and federal authorities. They believed that by creating enough chaos and demonstrating their power, they could force the United States government to recognize their independent state. This was not just criminal enterprise; it was, in their minds, a desperate, violent political statement, a last-ditch effort to stem the tide of assimilation and preserve what remained of their culture and land.

Their crimes quickly escalated in both frequency and brutality. They were accused of robbing dozens of individuals and businesses, often leaving a trail of death and terror in their wake. A particularly heinous series of events occurred in late 1895 when the gang, after robbing and killing several men, was also accused of the rape of two women, a mother and daughter, near Red Fork. These horrific acts cemented their image as depraved criminals, stripping away any romanticized notions of their "republican" aspirations and fueling a relentless pursuit by law enforcement.

The news of the gang’s atrocities spread like wildfire, igniting public outrage and prompting a massive manhunt. Federal marshals, tribal police, and citizen posses were mobilized, all determined to bring the young outlaws to justice. Among the most prominent figures in the pursuit was Deputy U.S. Marshal Frank Eaton, better known as "Pistol Pete," a legendary figure of the Old West whose reputation for relentless tracking and unwavering courage preceded him. Eaton, who had himself become a marshal after avenging his father’s murder, was intimately familiar with the rugged terrain and the dangerous characters that roamed Indian Territory.

The pursuit was relentless, a cat-and-mouse game played out across the unforgiving landscape of eastern Oklahoma. The gang, despite their youth and audacity, were ultimately no match for the organized might of the law. Worn down by constant evasion, lack of resources, and the ever-present threat of capture, their dream of an Indian Republic crumbled under the weight of their own violence and the overwhelming pressure from their pursuers.

On December 15, 1895, after weeks of dodging marshals, the Rufus Buck Gang was finally cornered. Exhausted and surrounded near Big Creek in the Creek Nation, they surrendered to a posse led by Deputy Marshal Eaton. Their violent spree, which had lasted less than six months, was over.

The captured gang members were transported to Fort Smith, Arkansas, the seat of the legendary "Hanging Judge" Isaac C. Parker’s federal court. Parker, a stern and unyielding jurist, presided over one of the most famous and feared courts of the American frontier. Known for his unwavering commitment to justice – and his astonishing record of convictions and death sentences – Parker was the ultimate arbiter of law and order in Indian Territory. His court had jurisdiction over the vast, often lawless, expanse, and his reputation for swift and severe justice was well-earned. Over his 21-year tenure, he sentenced 160 people to hang, 79 of whom were ultimately executed, earning him the moniker "The Hanging Judge."

The trial of Rufus Buck and his gang was swift and conclusive. They were charged with a litany of crimes, including robbery, rape, and murder. The evidence against them, particularly the murder of Gus Storey and the testimony regarding the sexual assaults, was overwhelming. Despite their youth, no mercy was granted. All five members – Rufus Buck, Lewis Davis, Sam Sampson, Maoma July, and Lucky Davis – were found guilty and sentenced to hang.

On July 1, 1896, the sun rose over Fort Smith for the last time for the Rufus Buck Gang. They were led to the infamous gallows, a grim wooden structure capable of executing multiple individuals simultaneously. It was a stark, public spectacle designed to instill fear and demonstrate the unyielding power of federal law. Before a crowd of onlookers, the five young men, whose violent dream of an Indian Republic had dissolved into a nightmare, met their end. They were the last group of outlaws to be collectively hanged at Fort Smith under Judge Parker’s jurisdiction, marking a symbolic close to an era of frontier justice.

The story of Rufus Buck and his gang is more than just a tale of frontier lawlessness; it is a poignant, if brutal, footnote in the larger narrative of American expansion and the subjugation of indigenous peoples. Their desperate bid for an Indian Republic, however misguided and violent, speaks to the profound sense of grievance and powerlessness felt by many Native Americans as their lands and cultures were systematically dismantled.

Rufus Buck remains a complex, often reviled, figure. He was a criminal who committed horrific acts, yet he also represented a tragic, violent resistance against an overwhelming force. His story, and that of his gang, is a stark reminder of the harsh realities of the late 19th-century American frontier, a place where justice was often swift and brutal, and where the dreams of an independent indigenous future were ultimately crushed under the inexorable march of Manifest Destiny. The ghost of Rufus Buck, and the violent republic he envisioned, continues to haunt the historical memory of Indian Territory, a testament to the turbulent birth of a state and the enduring legacy of conflict and loss.