Echoes of the Frontier: Unearthing the Legacy of Cantonment Jordan, Montana

In the vast, untamed heart of Eastern Montana, where the horizon stretches into infinity and the sky feels impossibly wide, lies the small, resilient town of Jordan. A county seat for Garfield County, Jordan today is home to just over 300 souls, a bastion of self-reliance clinging to a landscape that is both breathtakingly beautiful and brutally unforgiving. But before it was Jordan, the platted town, it was something else – a fleeting, foundational entity known intriguing as Cantonment Jordan. This name, redolent of military outposts and temporary encampments, hints at a story far richer and more complex than a simple dot on a map; it speaks to the very essence of frontier ambition, the struggle for survival, and the enduring spirit of the American West.

The name "Cantonment" often conjures images of military barracks or temporary garrisons. Yet, Cantonment Jordan was not a military base in the traditional sense. Instead, it was the nascent encampment, the temporary settlement that preceded the official town of Jordan, born out of the relentless push of civilization into the last wild places. Its genesis lies in the early 20th century, a period when Montana was still a land of opportunity for homesteaders, ranchers, and those seeking to carve out a new life from the raw earth.

The story begins with a surveyor named John E. Jordan. Tasked with mapping and delineating the sprawling, unorganized territory that would eventually become Garfield County, Jordan established a camp in 1912 near the confluence of the Big Dry Creek and the Missouri River breaks. This camp, a collection of tents and crude log structures, served as a base of operations for his crew. It was a temporary, functional settlement, and thus, fittingly, it became known as Cantonment Jordan. This humble camp quickly attracted others – prospectors, cattlemen, and hopeful settlers – drawn by the promise of free land and the burgeoning cattle industry. By the time the townsite was officially platted in 1912 and named simply "Jordan" in honor of its progenitor, the "cantonment" had already laid the foundational stones for what would become a permanent community.

"It wasn’t a military fort, no," explains Martha Caldwell, a local historian whose family roots in Garfield County stretch back to the homestead era. "It was the first foothold, the place where folks stopped to catch their breath before really digging in. John Jordan planted a flag, and others came to see what was there." This initial encampment was more than just a place to sleep; it was a nexus of ambition, a gathering point for the disparate threads of the frontier experience. It was where supplies were offloaded from steamboats navigating the Missouri River, where mail was distributed, and where the first semblance of law and order began to take shape in a land notorious for its lawlessness.

The early years of Jordan, born from its cantonment roots, were marked by a heady mix of optimism and brutal reality. The promise of the Homestead Act, offering 160 acres of land to anyone willing to cultivate it for five years, drew thousands to Montana. Garfield County, vast and largely unpopulated, became a magnet. Cattle ranching quickly became the economic backbone, with vast herds grazing on the open range. But the land, while bountiful, was also a harsh mistress. Blistering summers, frigid winters, and unpredictable droughts tested the mettle of even the most determined settlers.

"My great-grandparents often spoke of the winters," Caldwell recounts, leafing through old photographs. "Snowdrifts taller than a man, temperatures that could freeze the very hope out of you. But they stayed. They had to. They’d put everything they had into this land." This resilience, forged in the crucible of extreme weather and isolation, became a defining characteristic of Jordan’s populace.

One of the most defining aspects of Jordan’s early development, and indeed its character even today, is its profound isolation. Unlike many towns of the American West that sprang up along railroad lines, Jordan remained stubbornly off the beaten path. The nearest major railhead was miles away, meaning supplies had to be freighted in by wagon, a journey that could take days or even weeks over rugged, unpaved terrain. This geographical remoteness, while challenging, also fostered a fierce sense of self-reliance and community. "When you’re that far from anywhere," a grizzled rancher once famously remarked, "you learn to depend on your neighbor, because there’s nobody else."

The cattle industry, though lucrative, was not without its perils. Cattle rustling was rampant in the early 20th century, and Jordan found itself at the heart of many disputes. Tales of daring raids, desperate chases, and frontier justice are woven into the fabric of the town’s oral history. Sheriffs were often outnumbered and outgunned, relying on community support and their own grit to maintain order. The town itself, still raw and unrefined, reflected this untamed spirit.

As the 1920s roared on, Jordan saw periods of boom, particularly with the discovery of oil and gas in the surrounding areas. Small, independent wildcatters flocked to the region, dreaming of striking it rich. While no massive oilfields materialized directly around Jordan, the exploratory activity and the hope it generated kept the town buzzing for a time. However, this boom proved ephemeral. The Great Depression, coupled with the devastating Dust Bowl years of the 1930s, brought the region to its knees. Drought withered crops, cattle prices plummeted, and many homesteaders, unable to sustain themselves, abandoned their dreams and their land, leaving behind desolate farmsteads as monuments to shattered hopes. Jordan, like countless other rural communities, saw its population dwindle.

Yet, Jordan endured. Those who remained were the truly tenacious, individuals whose roots were too deep or whose spirit too stubborn to be broken. They diversified, adapted, and held onto their land, often through sheer force of will. World War II brought new demands and opportunities, as agricultural products were needed for the war effort, but the long-term trend of rural depopulation continued into the latter half of the 20th century. Mechanization in agriculture meant fewer hands were needed on the land, and young people increasingly sought opportunities in larger towns and cities.

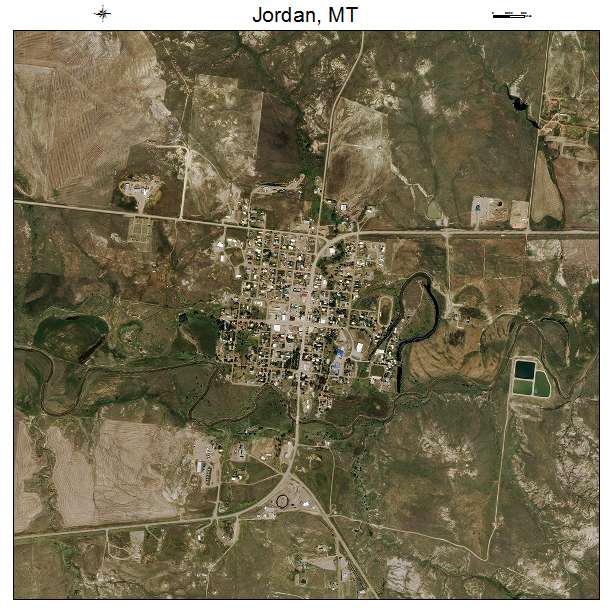

Today, Jordan exists as a testament to this enduring legacy. Its population has stabilized, hovering around 300-400 residents, but its role as the county seat of Garfield County—one of the largest and most sparsely populated counties in the continental United States—remains vital. It is a hub for ranchers, hunters, and those who seek the quiet solitude of the Montana plains.

The town’s identity is inextricably linked to its unique natural surroundings. Jordan sits within striking distance of the Missouri River Breaks National Monument, a rugged, breathtaking landscape of eroded badlands, deep canyons, and vast expanses of sagebrush and prairie. This area is not only a haven for wildlife – elk, deer, bighorn sheep, and various bird species – but also a paleontological goldmine. The Hell Creek Formation, famous for its rich dinosaur fossil beds, underlies much of the region. Legendary finds, including numerous Tyrannosaurus rex and Triceratops specimens, have been unearthed nearby, drawing paleontologists and enthusiasts from around the globe.

"We might be small, but we’re surrounded by giants, both past and present," says Jim Peterson, a local outfitter who guides hunters and dinosaur enthusiasts. "The land here, it tells stories if you just know how to listen. From the fossilized bones of a T-Rex to the ghost towns of the homesteaders, it’s all part of the same grand narrative." This geological and historical richness provides a unique draw, contributing to Jordan’s identity as more than just a remote agricultural outpost.

The challenges Jordan faces today are familiar to many rural American towns: maintaining essential services, attracting new businesses, and combating an aging population. Yet, there’s an undeniable spirit of optimism and community pride. Locals are fiercely protective of their way of life, their independence, and the tight-knit bonds that define their society. The school remains a central pillar, and local events, from rodeos to county fairs, are celebrated with gusto, bringing together residents from across the vast county.

The legacy of Cantonment Jordan, the temporary camp that blossomed into a resilient town, is not just found in history books or old maps. It lives on in the spirit of its people – a spirit of self-reliance, community, and an unyielding connection to the land. It is a reminder that even the most fleeting of human endeavors can lay the groundwork for something lasting, something that defies the odds and continues to echo the enduring call of the frontier. In a world increasingly homogenized, Jordan, Montana, stands as a quiet, powerful testament to the rugged individualism and tenacious community that built, and continues to sustain, the American West.