Where Destiny Crossed the Kaw: The Unsung Saga of Vieux’s Ferry and the Forging of Kansas

The American West, a landscape etched into the national psyche, was not conquered by grand armies alone, but by the relentless determination of countless individuals. Among them were the entrepreneurs, the pathfinders who saw opportunity where others saw only impenetrable wilderness. One such figure was Louis Vieux, a man of Métis heritage whose shrewd vision transformed a treacherous river crossing in the heart of Kansas into a vital artery for westward expansion, shaping the destiny of a territory and an entire nation. His ferry and later bridge across the Kansas River, known simply as Vieux’s Crossing, stands as a forgotten monument to frontier ingenuity, cultural confluence, and the sheer grit required to build a new world.

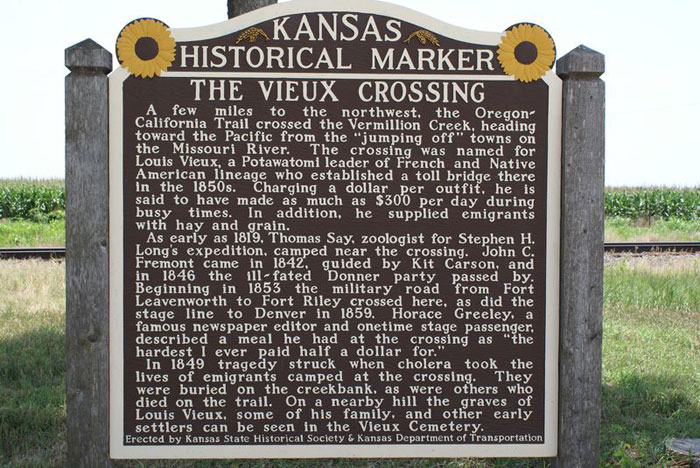

Today, if one drives through the fertile plains of Pottawatomie County, Kansas, near the unassuming town of St. Marys, the casual observer might notice a historical marker or a local road named "Vieux Road." These are subtle whispers of a bygone era, faint echoes of a place that, for several critical decades in the mid-19th century, pulsed with the lifeblood of Manifest Destiny. From the 1840s through the 1870s, Vieux’s Crossing was not merely a point on a map; it was a bottleneck, a lifeline, and a crossroads where thousands of emigrants, soldiers, traders, and dreamers paused, paid, and pressed onward, their hopes and fears carried on the current of the Kaw River.

Louis Vieux was a man uniquely positioned to bridge worlds, both literally and figuratively. Born around 1809 in what is now Michigan, he was of French-Canadian and Pottawatomi descent. This mixed heritage was not uncommon on the frontier, but Vieux leveraged it with exceptional skill. He understood the land, the rivers, and, crucially, the people – both Native and Euro-American – who navigated this shifting landscape. When the Pottawatomi people were relocated to a reservation along the Kansas River (also known as the Kaw River) in the early 1840s, Vieux moved with them, establishing himself near the confluence of the Vermillion River and the Kaw. It was here that he recognized an unparalleled opportunity.

The Kansas River, a formidable tributary of the Missouri, posed a significant barrier to westward travel. Its width, often unpredictable currents, and seasonal flooding made it a perilous obstacle for wagons laden with supplies and families eager to reach Oregon, California, or the Mormon settlements in Utah. While other, more rudimentary crossings existed, Vieux identified a strategic location where the river banks offered a relatively stable approach and departure. With characteristic enterprise, he established a ferry operation, a simple but invaluable service that quickly became indispensable.

The timing was impeccable. The 1840s saw the trickle of pioneers on the Oregon Trail swell into a steady stream, soon to become a torrent with the discovery of gold in California in 1848. Thousands upon thousands of emigrants, their covered wagons forming long, dusty processions, converged on the Missouri River towns, preparing for the arduous journey west. Their first major challenge upon leaving the settled frontier was often the Kaw River. Vieux’s Ferry became one of the primary gateways to the vast, untamed territories beyond.

"Imagine the scene," recounts local historian Sarah Jensen, drawing on countless pioneer diaries and journals. "After weeks of travel just to get to the Missouri border, these families faced the Kaw. It wasn’t just a river; it was a psychological barrier. Vieux’s operation wasn’t just a service; it was a beacon of civilization, a promise of passage, and a vital first step into the true wilderness."

Vieux’s business was more than just a ferry. He operated a small trading post, providing essential supplies, repairs, and perhaps even rudimentary lodging. His Métis background gave him an advantage, allowing him to navigate the complex social and economic dynamics of the frontier. He held a license from the Pottawatomi tribal council, ensuring his legitimacy in a territory where land rights and jurisdictional authority were constantly contested. His operation was a microcosm of frontier capitalism, providing a critical service, generating income, and becoming a significant economic hub in the nascent Kansas Territory.

The charges for crossing were not insignificant, reflecting the value of the service and the inherent risks. A typical wagon and team might cost anywhere from one to five dollars, a considerable sum in the mid-19th century. Yet, for those with dreams of gold or fertile farmland, it was a price worth paying to avoid the dangers of attempting to ford the river themselves, or the delays of waiting for conditions to improve. Vieux’s boats, ranging from simple rafts to more sophisticated flatboats, were sturdy and reliable, expertly managed by his crew.

The challenges were manifold. The Kaw River was notorious for its floods, which could swell its banks dramatically, making crossing impossible for days or even weeks. Winter brought ice, shutting down operations entirely or requiring dangerous, makeshift solutions. Disease, a constant companion on the trails, also threatened the crossing community. Despite these obstacles, Vieux adapted and persevered, a testament to his resilience and business acumen.

As traffic continued to grow, the limitations of a ferry became apparent. The sheer volume of wagons often created long queues, stretching for miles, with emigrants sometimes waiting days for their turn. This bottleneck spurred Vieux to innovate. In the early 1850s, he embarked on a more ambitious project: a toll bridge. This permanent structure, built with timber, offered a faster, more reliable, and safer crossing, solidifying Vieux’s monopoly on this crucial segment of the trails. The bridge, likely a combination of pile trestle and perhaps some truss sections, represented a significant investment and a bold leap of faith in the future of westward expansion.

Vieux’s Crossing existed during a tumultuous period in American history. The 1850s saw Kansas become a battleground for the soul of the nation, as pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions clashed violently in what became known as "Bleeding Kansas." While not a direct site of combat, Vieux’s Crossing undoubtedly played a role in these conflicts. It served as a vital transit point for both settlers and armed parties entering the territory, ferrying abolitionists and border ruffians alike. The crossing’s strategic importance was not lost on military strategists either, as it facilitated the movement of troops and supplies during various skirmishes and later, during the Civil War.

The golden age of Vieux’s Crossing, however, was destined to fade. The relentless march of progress, which it had so ably served, eventually rendered it obsolete. The completion of transcontinental railroads in the late 1860s and early 1870s dramatically altered the landscape of transportation. No longer did emigrants rely solely on wagon trains; trains offered a faster, safer, and often more affordable alternative. New towns sprang up along the railway lines, and new bridges were constructed to serve these burgeoning communities.

By the late 1870s, the once-bustling hub of Vieux’s Crossing had largely fallen silent. The bridge, no longer profitable to maintain, likely deteriorated and was eventually abandoned or dismantled. Louis Vieux himself passed away around 1872, leaving behind a substantial estate and a legacy that, for a time, overshadowed his contributions. His descendants remained in the area, but the era of the great overland trails and the frontier entrepreneur was drawing to a close.

Yet, the story of Vieux’s Crossing is more than just a footnote in transportation history. It embodies several profound themes of the American experience. It is a testament to the power of individual enterprise and the ability of resourceful individuals to shape the course of history. It highlights the complex, often synergistic, relationship between Native American communities and Euro-American settlers, where cooperation and trade sometimes trumped conflict. Louis Vieux, a man of mixed heritage, facilitated the passage of a nation westward, demonstrating how cultural understanding could be a powerful tool for progress.

Moreover, Vieux’s Crossing serves as a potent reminder of the sheer physical effort and ingenuity required to navigate and settle the vast American frontier. Every wagon that rumbled across his ferry or bridge, every dollar exchanged, every weary traveler who found temporary respite, contributed to the forging of Kansas and the expansion of the United States. It was a site where the abstract concept of Manifest Destiny met the tangible reality of a muddy river and the need for a way across.

Today, the site of Vieux’s Crossing is quiet, marked primarily by history and memory. But its enduring legacy lies not just in the historical markers, but in the very fabric of Kansas itself. It was a crucial choke point, a necessary passage, and a vibrant center of commerce that helped transform an untamed territory into a settled state. Louis Vieux, the Métis entrepreneur, may not be as famous as the explorers or generals of his era, but his contribution was no less significant. He built a bridge, not just across a river, but between the old world and the new, between diverse cultures, and between the dream of westward expansion and its arduous reality. His crossing was a vital stitch in the tapestry of the American West, a place where destiny, quite literally, crossed the Kaw.