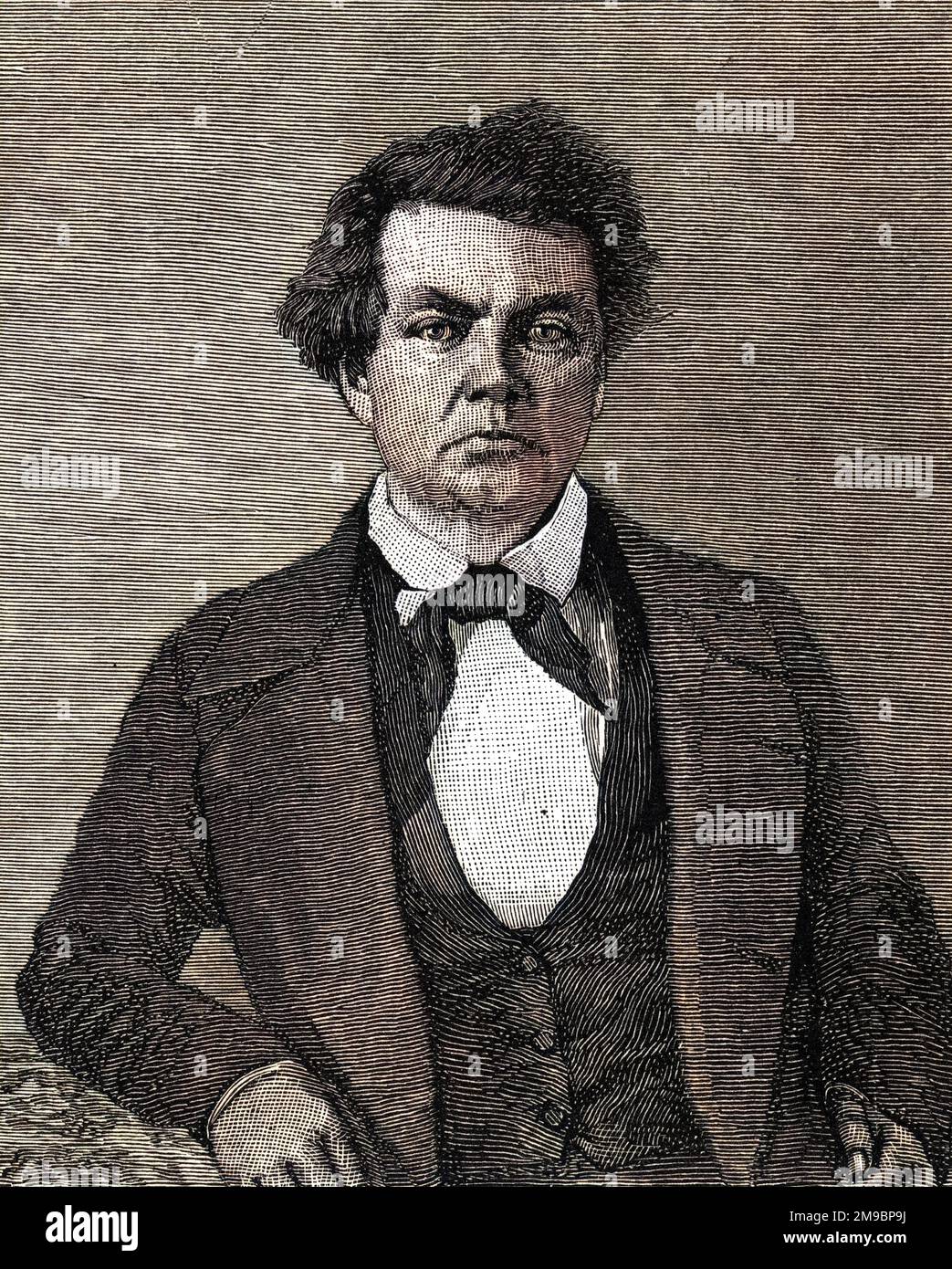

The Unvarnished West: Charles Preuss, Frémont’s Meticulous Cartographer and Candid Chronicler

In the grand narrative of America’s westward expansion, figures like Lewis and Clark, Kit Carson, and John C. Frémont loom large – explorers, pathfinders, and heroes whose exploits captured the national imagination. Yet, often overshadowed by these charismatic trailblazers are the meticulous scientists and unsung chroniclers whose painstaking work provided the very bedrock of understanding for this vast, mysterious continent. Among them, Charles Preuss stands out: a German cartographer whose precise maps literally redrew the American West, and whose private journals offered an unflinching, often grumbling, counter-narrative to the romanticized accounts of his more celebrated companions.

Preuss was no romantic. He was a man of precision, of scientific rigor, whose passion lay not in the thrill of discovery but in the accurate depiction of terrain, flora, and astronomical observations. Born in Höxter, Prussia, in 1803, Preuss received a meticulous education in cartography and mathematics, skills he honed in Europe before emigrating to the United States in 1834. It was this background that made him indispensable to John C. Frémont, the ambitious young army officer whose expeditions would become legendary.

Frémont, known as "The Pathfinder," was a visionary, a gifted writer, and a political operator, but he was no cartographer. He needed someone with the technical expertise to translate his observations and the expedition’s data into accurate, usable maps. Preuss, with his Prussian discipline and keen eye for detail, was the perfect foil. Their partnership, forged over three grueling expeditions between 1842 and 1848, would fundamentally alter America’s understanding of its western frontier, but it was also a relationship fraught with tension, as revealed by Preuss’s remarkably candid journals.

The First Forays: Mapping the Rockies

Preuss joined Frémont’s first expedition in 1842, a reconnaissance mission to the Rocky Mountains, specifically the Wind River Range. This initial journey was a baptism by fire for Preuss, introducing him to the raw, untamed wilderness of the American interior. Armed with a chronometer, sextant, barometer, and the then-state-of-the-art surveying instruments, Preuss began his monumental task. His method involved a combination of astronomical observations to determine latitude and longitude, triangulation for local detail, and "dead reckoning" – estimating position and distance traveled based on compass bearings and speed – a remarkably accurate system when executed by a master like Preuss.

The map resulting from this expedition, published in 1843, was a revelation. It delineated the Oregon Trail with unprecedented accuracy, depicted the formidable peaks of the Rockies, and corrected numerous errors from previous, less scientific surveys. For the first time, settlers and policymakers had a reliable guide to the initial leg of the westward journey. Preuss’s contribution was immense, though often buried within Frémont’s more dramatic official reports.

The Great Basin and the Sierra Nevada: A Cartographic Masterpiece

It was the second expedition (1843-1844) that truly cemented Preuss’s legacy and offered the richest insights into his character. This journey took the party deep into the heart of the Great Basin, a vast, arid expanse previously only vaguely understood, and then, in a daring winter crossing, over the formidable Sierra Nevada mountains into California.

Preuss worked relentlessly. Day after day, often in the saddle, he meticulously recorded distances, bearings, and astronomical readings. At night, by firelight, he would process the data, sketching, calculating, and drawing. His dedication was unwavering, even as the expedition faced extreme hardships. His journal entries from this period are a fascinating counterpoint to Frémont’s more heroic accounts. While Frémont described the grandeur of the landscape and the triumphs of discovery, Preuss detailed the misery.

"Always the same, always the same," he wrote, "eating nothing, sleeping little, always on horseback, always the same landscape." His complaints were frequent and often directed at the monotony, the hunger, the cold, and even Frémont’s leadership. "It is a wretched life," he noted, "and for what? To write a big book and to be called ‘The Pathfinder’ by the Americans." This sardonic wit and brutal honesty provide a refreshing, human perspective on the myth-making of westward expansion.

The winter crossing of the Sierra Nevada was particularly brutal. The party, near starvation, struggled through deep snow and icy winds. Preuss, ever the pragmatist, documented the dwindling supplies, the emaciated animals, and the growing desperation. Yet, amidst this suffering, his commitment to his craft never wavered. The map he produced from this expedition, published in 1845, was a landmark achievement. It was the first accurate depiction of the Great Basin, confirming its interior drainage system, and provided the first reliable map of the Sierra Nevada and the route to the Pacific. This map, incredibly detailed for its time, became the standard for decades, influencing countless pioneers and future surveys.

The Disillusionment: Third Expedition and Beyond

Preuss joined Frémont for a third expedition (1845-1846), which also ended in California, coinciding with the outbreak of the Mexican-American War and Frémont’s controversial involvement in the Bear Flag Revolt. By this point, Preuss’s journals reveal an even deeper weariness and disillusionment. The hardships were compounded by political intrigue, and Preuss, a man of science, found himself increasingly uncomfortable with the military and political machinations unfolding around him. His entries became more openly critical of Frémont’s decisions and the overall purpose of the journey.

"Frémont," he wrote, "is a little too much of the general and too little of the scientist." He often complained about the lack of proper food, the forced marches, and the seemingly arbitrary nature of their movements. He felt his scientific work was often subordinated to Frémont’s political ambitions. Despite his growing personal frustrations, Preuss continued to perform his duties with unwavering professionalism. The maps resulting from this expedition further refined the understanding of California and the Southwest.

After the third expedition, Preuss largely severed his ties with Frémont. While he continued to work on mapping projects for the government, his days of arduous frontier exploration were over. His final years were spent in Washington D.C., where he continued his cartographic work until his death in 1854.

The Legacy of Precision and Honesty

Charles Preuss’s contributions to American history are twofold. First, and most overtly, are his maps. These were not merely artistic renderings but scientific documents of unparalleled accuracy for their time. They provided the practical knowledge necessary for westward migration, agricultural development, and military strategy. His maps guided countless pioneers on the Oregon and California Trails, shaped territorial boundaries, and formed the foundation for future cartographic endeavors. He was a master of his craft, turning raw data into clear, navigable representations of a vast and complex landscape.

Second, and perhaps more enduringly fascinating, are his journals. These personal writings, translated and published long after his death, offer a rare and invaluable glimpse into the gritty reality of frontier exploration. Unlike Frémont’s polished, often self-aggrandizing official reports, Preuss’s journals are a raw, unfiltered account of the daily grind, the constant discomfort, the gnawing hunger, and the sheer monotony of life on the trail. He complained about the food, the weather, the leadership, and the endless tedium of his work, yet he never ceased to perform it with utmost dedication.

His observations often cut through the romantic veneer of exploration, revealing the human cost and the unglamorous truths that underpin grand narratives. For instance, while Frémont might describe a magnificent vista, Preuss might note the lack of fodder for the horses or the dwindling supply of coffee. He humanizes the experience, making the explorers not just heroic figures but also ordinary men struggling with extraordinary circumstances. His critical perspective serves as a vital historical corrective, reminding us that even the most ambitious endeavors are carried out by individuals with their own anxieties, frustrations, and private thoughts.

In a historical landscape often dominated by larger-than-life personalities, Charles Preuss remains a quiet, meticulous force. He was the unsung hero of precision, the tireless craftsman whose detailed work made the romantic visions of others possible. His maps guided a nation, and his journals continue to offer a unique, unvarnished window into the true grit and grime of America’s westward expansion. He might have grumbled his way across the continent, but in doing so, Charles Preuss drew a clearer picture of the American West than anyone before him, leaving an indelible mark on both our understanding of the land and the human experience of exploring it.