The Culinary Civilizer: Fred Harvey’s Enduring Legacy on American Hospitality and the West

Imagine traversing the vast, untamed American West in the late 19th century. Travel was arduous, slow, and often miserable. For days on end, passengers on newly laid rail lines endured cramped conditions and, perhaps worst of all, an abysmal culinary landscape. Meals were an afterthought, served in grimy "eating houses" or from baskets of questionable provenance, offering greasy, unappetizing fare that often left travelers sick and disillusioned. It was a frontier where even basic comforts were scarce, let alone refinement.

Then came Fred Harvey, a British immigrant with an audacious vision. He didn’t just want to feed people; he wanted to civilize the West, one impeccably served meal at a time. From a single lunch counter in Topeka, Kansas, in 1876, Harvey built an empire of hospitality that stretched across the American Southwest, transforming the travel experience, empowering women, and leaving an indelible mark on the very fabric of American culture. His Harvey Hotels and Restaurants were not merely establishments; they were oases of elegance, efficiency, and exceptional service in a rugged land, setting unprecedented standards that continue to influence the hospitality industry today.

The Man Behind the Vision: Fred Harvey’s Genius

Fred Harvey, born in London in 1835, arrived in New York in 1853 with little more than ambition. He worked his way up through various jobs, including a steamship line and a freight business, eventually becoming a successful restaurateur in St. Louis. It was his frequent rail journeys that ignited his revolutionary idea. Dismayed by the dreadful food served along the railroads, he saw an immense opportunity. "The food served along the railroad was simply terrible," Harvey famously observed, a sentiment that fueled his resolve. He envisioned a system that would offer consistent quality, cleanliness, and service, elevating the mundane act of eating to a dignified experience.

His initial proposal to the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad was rejected, but the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway, then a relatively new and ambitious line pushing westward, took a chance. In 1876, Harvey opened his first lunchroom in Topeka. The success was immediate and undeniable. Passengers, accustomed to slop, were astonished by white linen tablecloths, gleaming silverware, fresh ingredients, and courteous service. This was no ordinary frontier eatery; it was a beacon of refinement.

The Harvey House System: A Model of Efficiency and Quality

The partnership with the Santa Fe Railway was symbiotic. As the railway expanded its network across the vast plains and deserts, so too did Fred Harvey’s empire. Strategically located at key railway stops, often 100 miles apart – the distance a steam engine could travel before needing water and coal – Harvey Houses became essential waypoints. By their peak in the early 20th century, there were over 80 Harvey Houses, ranging from simple lunch counters to grand, sprawling hotel complexes.

What set them apart? Firstly, an unwavering commitment to quality. Harvey demanded the freshest ingredients, often sourcing them directly from his own farms and dairies or negotiating with local suppliers. Ice, a luxury in the desert, was crucial for preserving food and making refreshing drinks. Every detail, from the crispness of the lettuce to the temperature of the coffee, was meticulously controlled.

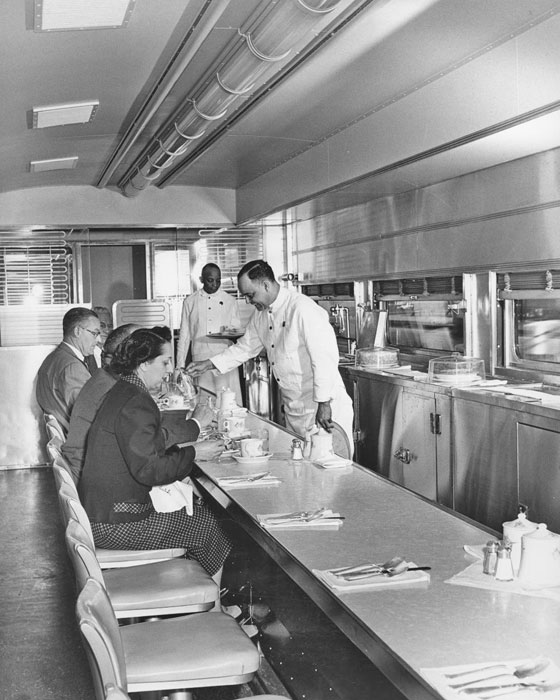

Secondly, standardization and efficiency were paramount. Harvey developed a rigorous system for everything. Meals were served with military precision; a train would pull in, passengers would disembark, eat a full, hot meal, and be back on board within 20-30 minutes. This required an army of well-trained staff, a precisely choreographed kitchen, and detailed menus that allowed for rapid preparation. "Eating your way across the continent" became a popular phrase, a testament to the reliability of Harvey’s establishments.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, was the impeccable service. Fred Harvey understood that presentation and attitude were as vital as the food itself. This led to his most innovative and enduring contribution: the "Harvey Girls."

The Harvey Girls: Pioneers of the Service Industry and Women’s Empowerment

In an era when respectable women rarely worked outside the home, especially in the rough-and-tumble West, Fred Harvey’s decision to employ young, single women as waitresses was revolutionary. He advertised for "young women, 18-30 years of age, of good character, attractive and intelligent," offering competitive wages, free room and board, and a chance for adventure. Thousands answered the call.

These "Harvey Girls" were meticulously trained. They wore crisp, black-and-white uniforms, their hair neatly tied back, adhering to strict rules of conduct. Chaperoned living quarters, curfews, and a ban on marriage during their initial contract were common. In return, they found economic independence, a safe environment, and opportunities for social mobility that were virtually nonexistent elsewhere. Many Harvey Girls eventually married local cowboys, ranchers, and railway workers, becoming matriarchs of Western families.

As historian Lesley Poling-Kempes notes in "The Harvey Girls: Women Who Opened the West," "These women were not just waitresses; they were ambassadors of civilization, bringing grace and order to a wild frontier. They were pioneers in their own right, shaping the social landscape of the West as much as the railroad itself." Their presence not only elevated the dining experience but also had a profound civilizing effect, fostering a more refined atmosphere in the otherwise rugged frontier towns.

Architectural Masterpieces and the Birth of Tourism

Beyond mere restaurants, Fred Harvey’s empire expanded into grand hotels, many designed by renowned architects and often featuring distinctive regional styles. Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter, one of America’s first prominent female architects, was instrumental in shaping the aesthetic of many Harvey properties, particularly those in the Southwest. Her designs blended seamlessly with the natural landscape and local culture, drawing inspiration from Pueblo, Mission Revival, and Spanish Colonial styles.

Iconic examples include:

- El Tovar Hotel at the Grand Canyon (Arizona): Built in 1905, perched directly on the South Rim, it offered luxury and breathtaking views, establishing the Grand Canyon as a premier tourist destination. Harvey’s company not only ran the hotel and restaurants but also organized mule trips and tours into the canyon, effectively pioneering tourism in the region.

- La Fonda on the Plaza (Santa Fe, New Mexico): Acquired by Harvey in 1925, this historic hotel became a centerpiece of Santa Fe’s cultural life, celebrated for its Pueblo Revival architecture, vibrant art, and authentic Southwestern cuisine.

- The Alvarado Hotel (Albuquerque, New Mexico): A grand Mission Revival complex opened in 1902, it featured a famous Indian Building and curio shop, showcasing Native American arts and crafts, further promoting regional culture and tourism.

- The Castaneda Hotel (Las Vegas, New Mexico): Built in 1898, this Mission Revival gem, recently restored, epitomized the luxury offered to rail travelers.

These hotels were not just places to sleep; they were destinations in themselves, showcasing local art, architecture, and culture, turning transient stops into memorable experiences. Harvey understood that the journey was as important as the destination, and he curated both.

The Golden Age and Gradual Decline

The Fred Harvey Company thrived through the early 20th century, reaching its zenith in the 1920s. It was a time when rail travel was king, and Harvey’s brand was synonymous with quality and adventure. However, the seeds of its eventual decline were sown with the rise of the automobile and the development of the national highway system. As more Americans took to the roads, bypassing rail lines and their accompanying Harvey Houses, the company’s core business model began to erode.

The Great Depression and World War II brought further challenges. While the war saw a resurgence in rail travel for troop movements, the post-war boom was driven by cars and air travel. Many of the grand Harvey Houses, once bustling hubs, became quieter, some closing their doors or being demolished. In 1968, the Fred Harvey Company was sold to Amfac Parks & Resorts (now Xanterra Parks & Resorts), marking the end of an independent era.

An Enduring Legacy

Despite the company’s eventual absorption, Fred Harvey’s legacy is far from forgotten. His innovations laid the groundwork for modern hospitality in countless ways:

- Standardization of Service: Harvey’s meticulous systems for quality control, efficiency, and staff training were revolutionary, influencing chain restaurants and hotels for generations.

- Customer Experience Focus: He understood that dining was about more than just food; it was about atmosphere, comfort, and attentive service. This customer-centric approach is now a cornerstone of the industry.

- Empowerment of Women: The Harvey Girls created a template for women’s entry into the service workforce, providing economic opportunities and fostering independence at a crucial time in American history.

- Pioneering Tourism: By developing hotels, curio shops, and organized tours, particularly at the Grand Canyon, Harvey helped to create and popularize American tourism as we know it.

- Architectural Preservation: Many of his iconic hotels and restaurants, like La Fonda, El Tovar, and the Castaneda, have been meticulously restored, serving as living museums and vibrant businesses that honor their rich past. The Fred Harvey Museum in Florence, Kansas, also preserves his story.

Today, echoes of Fred Harvey’s vision can be seen in the consistent quality of major hotel chains, the efficient operations of fast-casual restaurants, and the enduring allure of destination resorts. He proved that even in the most challenging environments, a commitment to excellence, coupled with astute business acumen and a touch of human warmth, could build an empire. Fred Harvey didn’t just feed the West; he nurtured its spirit, offering a taste of civility and a glimpse of a more refined future, one perfectly plated meal at a time.