The Unyielding Spirit: Nabor Pacheco and the Yaqui Struggle for Survival

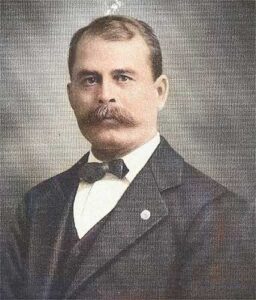

In the rugged, sun-baked landscapes of Sonora, Mexico, a saga of defiance unfolded at the turn of the 20th century, etched into the very soil by the unyielding spirit of the Yaqui people. At the heart of this epic resistance stood figures like Nabor Pacheco, a leader whose name, though less widely known than some, embodies the relentless struggle against an oppressive state, a symbol of indigenous determination in the face of brutal "progress." Pacheco was not just a warrior; he was a custodian of ancestral lands, a guardian of a sacred culture, and a beacon of hope for a people facing extermination.

To understand Nabor Pacheco, one must first grasp the profound connection of the Yaqui to their ancestral territory – the fertile Yaqui River Valley. For centuries, long before the arrival of the Spanish, the Yaqui had cultivated their lands, developing a sophisticated social and spiritual structure rooted in the "Eight Towns" (Pótam, Vícam, Tórim, Bácum, Cócorit, Huírivis, Rahum, Belem). They were a people fiercely independent, their history marked by a series of conflicts with both colonial and later Mexican authorities who coveted their rich agricultural lands and saw their self-governance as an impediment to national unity.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries brought this conflict to a head under the iron-fisted rule of Porfirio Díaz. The Porfiriato era, characterized by a veneer of "Order and Progress," was in reality a period of immense social inequality, economic exploitation, and brutal repression of indigenous populations. Díaz’s vision of a modernized Mexico hinged on the expansion of railroads, mining, and large-scale agriculture, all of which required vast tracts of land. The Yaqui River Valley, with its fertile soil and strategic location, became an irresistible target.

The Mexican government, particularly under the governorship of Luis Torres in Sonora, initiated a systematic campaign to dispossess the Yaqui. This was not merely a land dispute; it was a war of extermination, fueled by racism and the insatiable greed of wealthy landowners and foreign investors. The Yaqui, however, refused to be subjugated. Led by legendary figures like Cajeme (José María Leyva Pérez) and later Tetabiate (Juan Maldonado Waswechia), they mounted a formidable guerrilla resistance, utilizing their intimate knowledge of the harsh Sonoran terrain to outmaneuver and frustrate the better-equipped federal troops.

Nabor Pacheco emerged into this crucible of conflict, a torchbearer in a long line of Yaqui leaders. His exact origins are somewhat shrouded in the mists of oral tradition and the chaos of war, but his leadership qualities quickly became evident. He was known for his strategic acumen, his ability to rally his people, and his unwavering commitment to the Yaqui way of life. Following the death of Tetabiate in 1901, Pacheco, alongside other prominent leaders such as Sibalaume and Bule, continued the fight, refusing to lay down arms or concede their ancestral domain. Their resistance was not just political or military; it was deeply spiritual, a defense of their very identity as a people chosen to protect their sacred lands.

The government’s response to this continued defiance was genocidal. Unable to defeat the Yaqui outright, they resorted to scorched-earth tactics, massacres, and, most infamously, mass deportations. Thousands of Yaqui men, women, and children were rounded up, often under false pretenses of peace, and forcibly marched or transported by train to the distant, disease-ridden henequen plantations of Yucatán and the tobacco fields of Valle Nacional in Oaxaca. This brutal policy, orchestrated by Governor Torres and sanctioned by President Díaz, was designed to break the Yaqui spirit, to dissolve their communities, and to clear their lands for exploitation.

The conditions of these deportations and forced labor camps were horrific. Yaquis, accustomed to the dry, mountainous climate of Sonora, were thrust into the humid, tropical lowlands, where they quickly succumbed to malaria, dysentery, and the brutal labor regimen. Families were torn apart, men worked to death, women were exploited, and children perished from neglect and disease. It was a systematic attempt at cultural and physical annihilation.

It was during this dark period that Nabor Pacheco’s resilience shone brightest. Operating from the rugged Sierra del Bacatete, a natural fortress that had long served as a Yaqui stronghold, he and his band of guerrillas continued to wage war. They launched raids, ambushed federal troops, and disrupted government operations, always with the aim of drawing attention to their plight and reclaiming their stolen lands. Pacheco’s leadership was characterized by a deep understanding of his people’s spiritual beliefs, often incorporating traditional ceremonies and prophecies into their military strategies, reinforcing the idea that their struggle was divinely sanctioned.

The Yaqui resistance, though often overlooked in official Mexican histories, garnered international attention thanks to the courageous efforts of a few journalists. French journalist Marius Dubois, in articles for Le Journal in 1908, provided early, harrowing accounts of the Yaqui deportations. But it was the American journalist John Kenneth Turner, whose searing exposé, Barbarous Mexico, published in 1910, brought the Yaqui plight to the forefront of international consciousness. Turner meticulously documented the atrocities, writing:

"The Yaqui… is considered a wild animal, whose extermination is a virtue. This is the common view of the Mexicans in Sonora, a view shared by the Díaz government and expressed in the official policy of hunting, enslaving, and murdering the Yaquis."

Turner’s vivid descriptions of the Yaqui’s suffering, their forced labor, and the profits reaped by Mexican and American elites from their enslavement, exposed the hypocrisy of the "Order and Progress" rhetoric. He detailed how Yaqui families were sold for as little as 60 pesos per person, their lives reduced to mere commodities. These reports, though slow to impact policy, became powerful indictments of the Díaz regime and gave voice to the voiceless.

Nabor Pacheco and his fellow leaders, though likely unaware of the direct impact of these international reports, were living the reality Turner described. Their guerrilla warfare was not just about winning battles; it was about maintaining a presence, a visible sign that the Yaqui spirit remained unbroken. Each raid, each ambush, each refusal to surrender was an act of profound cultural and spiritual resistance. They embodied the Yaqui oath, "Never to surrender," passed down through generations.

The Yaqui Wars, enduring for decades, finally began to wane with the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution in 1910. The fall of Porfirio Díaz created a new, albeit chaotic, political landscape. Many Yaquis, including some led by Pacheco, initially aligned with revolutionary factions, particularly those led by figures like Álvaro Obregón, hoping that a new government might honor their claims and return their lands. Some Yaquis even fought with distinction in the revolutionary armies, believing it was a path to reclaiming their autonomy.

However, the promises of the Revolution proved largely illusory for the Yaqui. While some were eventually able to return from exile and some land was later restored, the struggle for full recognition and self-determination continued for decades. The exact fate of Nabor Pacheco remains somewhat debated, as is common for many guerrilla leaders whose lives were lived on the fringes of official records. Some accounts suggest he continued to lead his people in the Sierra, a symbol of resistance until his natural death, while others imply he may have been killed in skirmishes or even taken prisoner. Regardless of his ultimate personal end, his legacy endured.

Nabor Pacheco, like Cajeme and Tetabiate before him, represents the enduring spirit of the Yaqui people. His leadership in the face of overwhelming odds, his steadfast refusal to compromise on the sacred bond between his people and their land, and his courage in the face of genocidal policies serve as a powerful reminder of indigenous resilience. The Yaqui people, against all odds, survived. Their language, culture, and unique spiritual traditions persist to this day, a testament to the leaders like Nabor Pacheco who, through their unwavering defiance, ensured that the flame of Yaqui identity was never extinguished. His story is a poignant chapter in the larger narrative of indigenous resistance in the Americas, a call for justice that echoes through history, reminding us that true progress cannot be built on the annihilation of a people’s soul.