Fort Brewerton: Echoes of a Forgotten Empire at the Great Carrying Place

In the quiet, unassuming landscape of Central New York, where Oneida Lake narrows into the Oneida River, lies a testament to a pivotal era in North American history: Fort Brewerton. To the casual observer, it might appear as little more than a series of grassy mounds and depressions – a quaint park, perhaps, for a leisurely stroll. Yet, beneath this deceptive tranquility lies the outline of a star-shaped earthwork fort, a silent sentinel guarding what was once a critical choke point in the fierce struggle for a continent. Fort Brewerton, though never the scene of a grand siege or a decisive battle, was a linchpin in the British strategy during the French and Indian War, a humble yet indispensable cog in the machinery of empire.

To understand Fort Brewerton’s significance, one must first grasp the geography of the 18th century. Before railroads and highways, rivers and lakes were the arteries of commerce and conquest. The "Great Carrying Place," or "Oswego-Mohawk River portage," was a vital inland waterway connecting the Atlantic seaboard (via the Hudson and Mohawk Rivers) to the Great Lakes and the vast interior of North America. Supplies, troops, and trade goods flowed along this arduous route, a watery highway punctuated by portages where boats and cargo had to be hauled overland. Oneida Lake, a natural bottleneck in this system, served as a crucial transit point, and its western outlet into the Oneida River was a particularly vulnerable spot.

It was this strategic vulnerability that drew the attention of British military planners. The French, entrenched in Canada, routinely used their network of forts and allied Native American forces to disrupt British supply lines and threaten their western outposts, most notably Fort Oswego on Lake Ontario. Control of the Oswego-Mohawk route was paramount for the British to maintain their presence in the region and launch offensives against French Canada.

The fort’s construction began in 1759, a year that would prove to be a turning point in the French and Indian War, often referred to as "The Year of Miracles" for the British. Under the command of Sir William Johnson, the charismatic and influential Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Northern Department, British regulars and colonial militia began to erect a series of fortifications along the critical waterway. Johnson, who had forged deep alliances with the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, understood the terrain and the strategic imperatives intimately. Fort Brewerton was one of the last in this chain of defenses, built to secure the western end of Oneida Lake and protect the passage down the Oneida River towards Oswego.

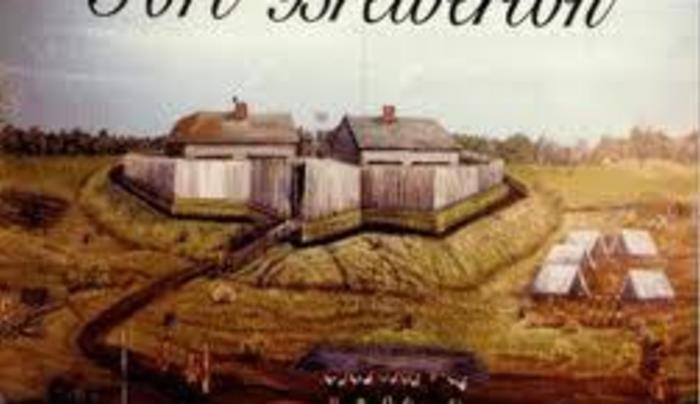

Unlike the grand stone bastions of Quebec or Louisbourg, Fort Brewerton was a more pragmatic and rapidly constructed defense. It was an earthwork fort, designed in a classic star shape, with a surrounding ditch and palisade. The star-shaped design, a common feature of 17th and 18th-century military architecture, allowed for interlocking fields of fire, meaning defenders could bring muskets and cannons to bear on any attacking force from multiple angles, leaving no "dead ground" for an enemy to exploit. Within its earthen walls, barracks, storehouses, and a magazine would have been erected, likely from timber and wattle-and-daub, providing shelter and security for the garrison. Its primary role was not to withstand a prolonged siege, but to act as a fortified waypoint, a supply depot, and a staging ground for troops moving through the region.

Life at Fort Brewerton would have been a harsh reality for the soldiers stationed there. Far from the comforts of settled towns, isolated in a vast wilderness, the garrison faced not only the threat of French and Native American skirmishes but also the relentless challenges of disease, boredom, and the unforgiving New York weather. Winters would have been brutal, with deep snows and freezing temperatures isolating the fort for months. Summers brought humidity, mosquitoes, and the constant threat of fever and dysentery, which often claimed more lives than enemy bullets.

"The solitude of the wilderness forts often broke a man’s spirit before any enemy blade could," wrote one contemporary historian, echoing the sentiments of many a soldier’s diary. Supplies were often late or spoiled, and rations meager. The men, a mix of British regulars, colonial militia, and sometimes allied Native American scouts, would have spent their days on guard duty, maintaining the fort’s defenses, drilling, and foraging for food and fuel. The presence of skilled Native American allies, particularly from the Oneida and Onondaga nations, was crucial. Their knowledge of the land, their tracking abilities, and their proficiency in woodland warfare were invaluable to the British. They served as guides, scouts, and sometimes as additional fighting men, making the fort a true melting pot of cultures and military traditions.

Despite its importance, Fort Brewerton’s active life was relatively short. By 1760, the tide of the war had decisively turned in favor of the British. Montreal fell that year, effectively ending French control in Canada. The Treaty of Paris in 1763 formally concluded the war, ceding vast territories, including Canada, to Great Britain. With the French threat eliminated, the strategic necessity of many frontier forts, including Fort Brewerton, rapidly diminished. Its garrisons were withdrawn, its palisades eventually rotted away, and its buildings fell into disrepair. The wilderness, ever-patient, began to reclaim the site.

For decades, the fort lay largely forgotten, its earthen ramparts slowly softening under the elements and being cultivated by local farmers. It wasn’t until the early 20th century, with a growing interest in preserving historical sites, that Fort Brewerton began its journey towards recognition and protection. In 1904, the property was acquired by the State of New York and designated a State Historic Site. Archaeological investigations over the years have confirmed the precise layout of the fort, revealing artifacts that offer glimpses into the daily lives of its 18th-century inhabitants – musket balls, pottery shards, uniform buttons, and tools.

Today, Fort Brewerton State Historic Site is a tranquil, publicly accessible park. The star-shaped earthworks are still discernible, a testament to the original design and the enduring nature of carefully constructed earthworks. Interpretive signs guide visitors, explaining the fort’s history, its strategic role, and the lives of those who served there. There are no grand buildings standing, no reconstructed palisades, but the outlines of the past are palpable for those who take the time to look and listen.

Visiting Fort Brewerton today is a contemplative experience. Standing atop the grassy ramparts, one can gaze out over the serene waters of Oneida Lake and the gentle flow of the Oneida River, imagining the bustling scene that once unfolded here: bateaux laden with supplies, soldiers marching, Native American canoes gliding silently, all against the backdrop of an untamed frontier. It’s a place where the whispers of history are carried on the breeze, where the ghosts of sentinels still seem to stand vigil, and where the echoes of muskets and distant commands can almost be heard.

Fort Brewerton reminds us that not all history’s critical junctures are marked by monumental battles. Sometimes, the unsung heroes are the logistical hubs, the supply lines, and the humble fortifications that ensured the flow of men and material. It was these seemingly minor strongholds that allowed larger campaigns to succeed, ultimately shaping the geopolitical landscape of a continent. Its unassuming appearance belies its profound importance as a silent witness to the birth of a nation and the struggle for dominance in North America. For those willing to look beyond the surface, Fort Brewerton offers a powerful connection to a past that, though quiet, continues to resonate with lessons of strategy, survival, and the enduring human spirit. It stands as a profound reminder that even the smallest, most forgotten fort can hold the weight of empires within its earthen embrace.