The Frisco: A Midwestern Giant’s Unreached Dream of San Francisco

The name alone conjures images of westward expansion, of steel rails glinting under a setting sun, stretching inexorably towards the Pacific. "St. Louis-San Francisco Railway" – or simply "The Frisco," as it was affectionately known – promised a grand transcontinental link, a direct artery from the Gateway City to the Golden Gate. Yet, for all its ambition, for all its significant impact on the American heartland and Southwest, the Frisco’s tracks never truly reached the shores of San Francisco Bay. This paradox, a testament to the audacious dreams and hard realities of American railroading, is central to understanding one of the nation’s most resilient and influential regional carriers.

From its humble beginnings in Missouri to its eventual absorption into a modern rail giant, the Frisco navigated financial panics, world wars, economic booms, and technological revolutions. It was a railroad forged in the crucible of American enterprise, a vital link for agriculture, industry, and passengers across thousands of miles, even if its ultimate namesake remained an elusive, aspirational star on the horizon.

The Audacious Naming: A Vision Beyond the Rails

The story of the Frisco truly begins in the mid-19th century, amidst a fervor for internal improvements and westward expansion. Its earliest ancestor, the Pacific Railroad of Missouri, began construction in 1853, aiming to connect St. Louis with the burgeoning territories to the west. However, the Civil War and financial woes hampered its progress.

It was in 1876, emerging from the ashes of bankruptcy, that the St. Louis & San Francisco Railway Company was incorporated. At this point, its rails extended little further than Vinita, Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma). The choice of "San Francisco" was not a geographical reality, but a bold declaration of intent, a strategic play for land grants and investor confidence. In an era of grand railroad schemes, where a name could evoke boundless potential, linking St. Louis directly to the Pacific Coast was the ultimate marketing coup. It suggested a future where the Frisco would be a vital artery in a transcontinental network, perhaps even building its own line across the vast Western deserts.

This aspirational naming convention was common in the era. Railroads often took names far grander than their existing trackage, hinting at future expansion and the economic development they promised to bring. For the Frisco, it became a part of its identity, a constant reminder of the frontier spirit that fueled its growth. While the physical connection never materialized under Frisco’s own steam, the dream of westward expansion permeated its corporate culture and drove its relentless march across the American landscape.

Forging the Network: Steel Tendrils Across the Heartland

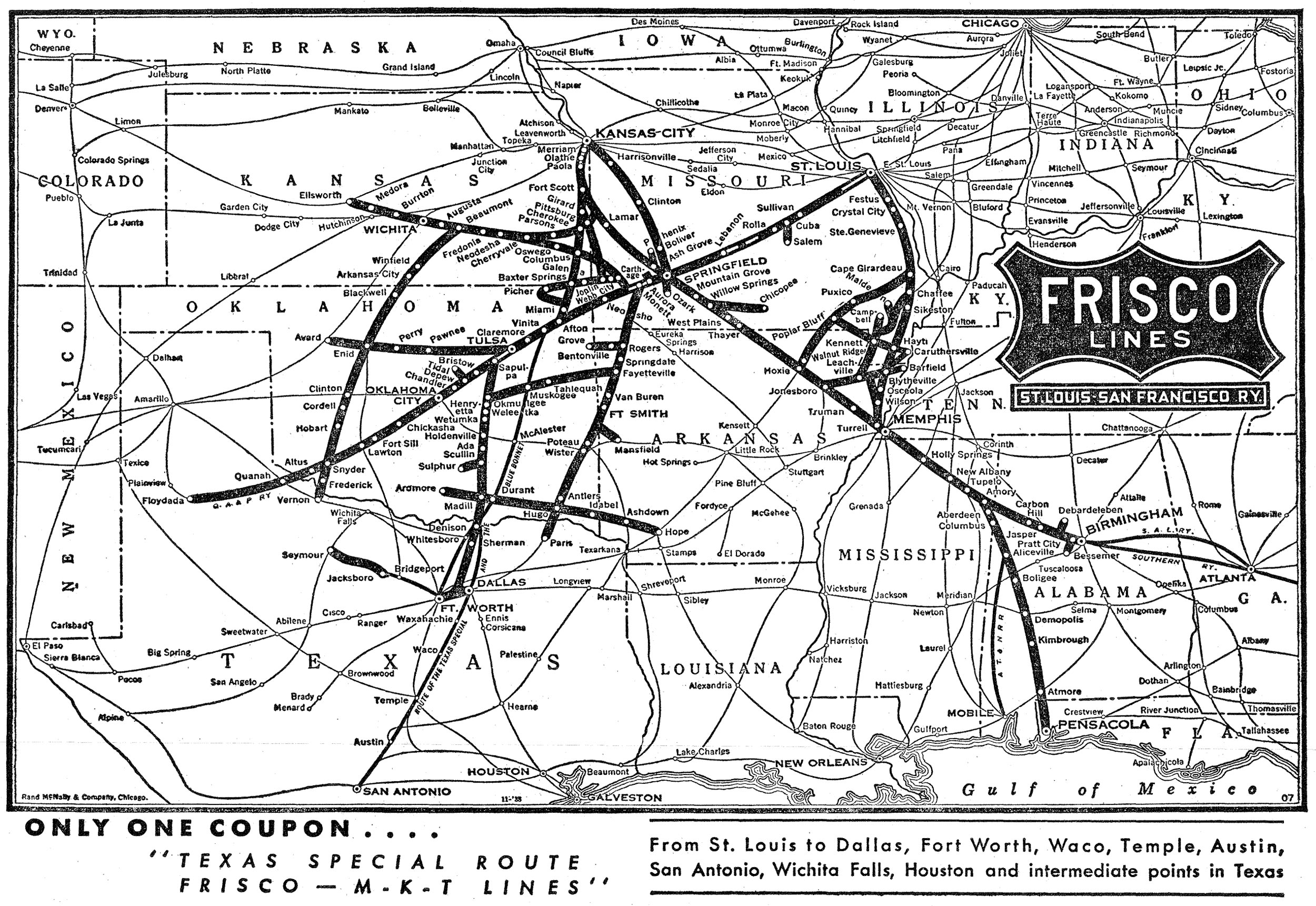

Despite not reaching its namesake, the Frisco wasted no time in establishing itself as a powerful force in the regions it did serve. Over the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it grew organically and through strategic acquisitions, weaving a complex web of tracks across the Midwest, Southwest, and even into the Southeast. Its core territory eventually encompassed Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Texas, Alabama, Mississippi, and Florida (via trackage rights).

By its peak, the Frisco operated over 5,000 miles of track, an impressive network that connected major cities like St. Louis, Kansas City, Springfield (MO), Tulsa, Oklahoma City, Fort Worth, Dallas, Memphis, Birmingham, and Mobile. It became an indispensable lifeline for these regions, transporting a diverse array of commodities:

- Agriculture: Grain, cotton, livestock from the fertile plains.

- Minerals: Coal from Oklahoma and Arkansas, iron ore from Alabama.

- Oil: The booming oil fields of Oklahoma and Texas provided a massive source of revenue, turning the Frisco into a key carrier for crude oil and petroleum products.

- Manufactured Goods: Connecting factories and markets across its vast territory.

The Frisco’s role in the development of Oklahoma, in particular, was profound. It was one of the first major railroads to extensively penetrate Indian Territory, facilitating settlement, commerce, and statehood. Towns sprang up along its lines, and its presence transformed isolated communities into thriving economic centers.

Innovation and Resilience: A Railroad Ahead of its Time

The Frisco cultivated a reputation for being well-managed, innovative, and resilient. Unlike some of its more flamboyant counterparts, it focused on efficiency, customer service, and adapting to changing economic landscapes. This pragmatic approach allowed it to navigate the turbulent waters of the early 20th century, including the Great Depression and two World Wars.

During World War II, like all American railroads, the Frisco played a crucial role in the war effort, moving troops, equipment, and supplies across the country with unprecedented speed and volume. Post-war, it was quick to embrace new technologies. The Frisco was an early adopter of dieselization, recognizing the efficiency and lower maintenance costs of diesel locomotives over steam. It was one of the first major railroads in the Southwest to completely dieselize its passenger fleet, a significant milestone that streamlined operations and improved service.

Its passenger trains, though not as nationally famous as some transcontinental limiteds, were renowned for their comfort and reliability within their service areas. The Meteor, running between St. Louis and Oklahoma City, was a sleek, modern streamliner that epitomized post-war passenger luxury. The Texas Special, operated jointly with the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad (MKT), provided a vital link between St. Louis, Kansas City, and major Texas cities like Dallas and San Antonio. These trains, with their distinctive Frisco red and white livery, became symbols of progress and connectivity for the communities they served.

Beyond motive power, the Frisco was also forward-thinking in its operational practices. It invested in Centralized Traffic Control (CTC), a system that allowed dispatchers to control switches and signals over long stretches of track from a central location, significantly improving efficiency and safety. This commitment to modernization helped the Frisco remain competitive in an increasingly challenging transportation environment, as highways and airlines began to erode the railroads’ traditional dominance.

Navigating the Modern Era: Challenges and Consolidation

The latter half of the 20th century presented immense challenges for American railroads. The rise of the interstate highway system, subsidized by the government, diverted massive amounts of freight traffic to trucks. The advent of affordable air travel decimated passenger rail ridership. Many railroads, once titans of industry, struggled to adapt, facing bankruptcies, mergers, and even abandonment of vast portions of their networks.

The Frisco, with its strong management and lean operations, fared better than many. It strategically focused on its most profitable freight lines, shedding less productive branches and aggressively marketing its services. It continued to innovate, investing in specialized freight cars and improved intermodal facilities to compete with trucking. Its diversified freight base, particularly its strong ties to the energy and agricultural sectors, provided a buffer against economic downturns.

However, the trend towards consolidation in the railroad industry was irresistible. To compete effectively in a continental market, smaller regional railroads increasingly found themselves needing to merge with larger systems. The prospect of creating more efficient, end-to-end routes and reducing redundant infrastructure drove this movement.

The Final Whistle: Merger into Burlington Northern

The dawn of the 1980s marked a poignant end to the Frisco’s independent existence. On November 21, 1980, the St. Louis-San Francisco Railway merged with the Burlington Northern Railroad (BN). The BN itself was a relatively new entity, formed in 1970 by the merger of the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad, the Great Northern Railway, the Northern Pacific Railway, and the Spokane, Portland and Seattle Railway.

The Frisco’s addition to the BN system was a significant move, creating a massive railroad network stretching from the Pacific Northwest to the Gulf Coast and the Southeast. The Frisco’s strong lines in the Southwest and Southeast perfectly complemented BN’s existing routes, providing crucial access to new markets and resources, particularly coal from the Powder River Basin and agricultural products from the Midwest. The merger was seen as a logical step to enhance efficiency and competitiveness in a rapidly evolving transportation landscape.

While the distinctive Frisco name and its unique identity were eventually absorbed, its legacy lived on. Many of its main lines continue to be vital arteries of commerce today as part of the BNSF Railway (formed by the 1995 merger of Burlington Northern and Santa Fe). The physical infrastructure, the routes painstakingly laid down by generations of Frisco railroaders, still carries the goods that fuel the American economy.

An Enduring Legacy

The St. Louis-San Francisco Railway may never have laid a single rail within sight of the Golden Gate, but its impact on the vast heartland of America is undeniable. It was a railroad built on ambition, sustained by resilience, and driven by a pragmatic commitment to efficiency and service. From its audacious naming to its innovative operations and its vital role in developing the Southwest, the Frisco embodied the spirit of American enterprise.

Its story is a reminder that while grand dreams may sometimes remain unfulfilled in their literal sense, the pursuit of those dreams can forge something equally significant and enduring. The Frisco, a steel backbone across the continent’s midsection, left an indelible mark on the landscape and economy of the United States, a true giant whose influence continues to resonate decades after its final whistle as an independent entity. Its name, a romantic whisper of a distant coast, forever etched in the annals of American railroading, serves as a testament to the power of vision and the hard-won triumphs of the iron horse.