Echoes on the Prairie: Fort Hays and the Forging of the American West

On the vast, windswept canvas of western Kansas, where the horizon stretches seemingly without end, stands a silent sentinel of a bygone era: Fort Hays. More than just a collection of historic buildings, this frontier outpost was a crucible where the forces of Manifest Destiny collided with the stubborn realities of the prairie, a strategic lynchpin in the violent, often romanticized, expansion of the American West. Though its active life spanned little more than a decade, Fort Hays cast a long shadow, playing host to legendary figures, witnessing pivotal conflicts, and ultimately helping to forge the modern landscape of Kansas and beyond.

To understand Fort Hays is to understand the frantic pace of post-Civil War America. The nation, scarred but unified, looked westward with unbridled ambition. The transcontinental railroad, a monumental undertaking, was slicing through the continent, promising to link east and west. But this progress came at a steep price, encroaching upon lands long inhabited by powerful Native American tribes – the Lakota, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, and Kiowa – who viewed the railway and the accompanying flood of settlers as an existential threat. It was into this volatile environment that Fort Hays was born.

A Strategic Locus in a Hostile Land

Established initially in 1865 as Fort Fletcher on Big Creek, a tributary of the Smoky Hill River, the post was quickly relocated and renamed Fort Hays in 1866, honoring Brigadier General Alexander Hays, a Union hero killed in the Battle of the Wilderness. Its strategic importance was immediately apparent: it sat directly on the route of the Kansas Pacific Railway, then known as the Union Pacific Railway, Eastern Division, which was pushing relentlessly westward. The fort’s primary mission was clear: protect the railroad workers, secure mail and supply routes, and safeguard the burgeoning trickle of settlers brave enough to venture into this often-hostile territory.

Life on the frontier, however, was no picnic. Soldiers stationed at Fort Hays faced a grueling existence. Summers brought scorching heat, dust storms, and swarms of insects, while winters descended with brutal blizzards and temperatures that plunged far below zero. Isolation was a constant companion, with the nearest significant settlements hundreds of miles away. Supplies were often scarce, and disease, particularly cholera, was a persistent threat, claiming more lives than enemy bullets. Yet, these hardy men, a mix of seasoned veterans and raw recruits, including the storied African American regiments known as the "Buffalo Soldiers," held the line.

Legends Walk Among Us: Custer, Cody, and the Buffalo Soldiers

Fort Hays’ brief history is inextricably linked with some of the most iconic figures of the American West. Perhaps the most famous was Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, whose 7th Cavalry was stationed at the fort intermittently between 1867 and 1869. Custer, known for his flamboyant personality and often controversial tactics, used Fort Hays as a base for campaigns against the Cheyenne and Sioux. His presence brought both excitement and notoriety to the remote outpost. While he was celebrated in the press as an Indian fighter, his time on the plains was also marked by incidents that foreshadowed his tragic end at the Little Bighorn, including a court-martial for abandoning his post and mistreating his men.

"Custer was a complex figure," notes Dr. Leo E. Oliva, a prominent Kansas historian. "He craved glory and adventure, and the Plains offered him that opportunity. Fort Hays was one of the stages where his legend, for better or worse, began to truly take shape."

Another legendary figure whose path frequently crossed Fort Hays was William F. "Buffalo Bill" Cody. While not a soldier at the fort, Cody was a civilian scout and buffalo hunter for the Kansas Pacific Railway, tasked with providing meat for the construction crews. It was in this capacity that he earned his famous nickname, reportedly killing thousands of buffalo. His exploits, often exaggerated and dramatized in dime novels, captivated the nation and helped solidify the romantic image of the daring frontiersman. Though his official duties were usually centered around the nearby settlement of Hays City, his connection to the fort and the surrounding plains was undeniable.

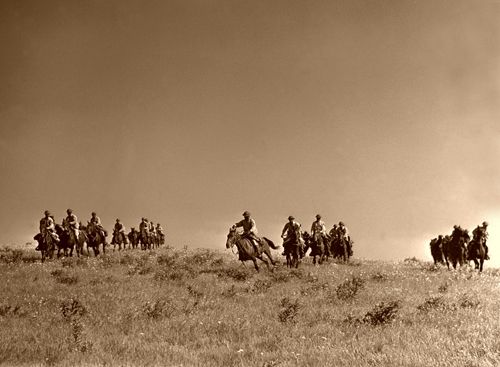

Equally, if not more, significant were the Buffalo Soldiers. The 10th U.S. Cavalry, composed entirely of African American soldiers and white officers, was headquartered at Fort Hays from 1867 to 1869. These courageous troops, often facing racial prejudice from both white settlers and fellow soldiers, earned their nickname from Native Americans who, impressed by their dark, curly hair and fierce fighting spirit, likened them to the revered buffalo. They played a vital role in protecting the railroad, escorting supply wagons, and conducting patrols, performing their duties with unwavering dedication under the harshest conditions. Their service at Fort Hays stands as a powerful testament to their resilience and their contribution to securing the frontier.

The "Indian Wars" and a Shifting Frontier

The decade of Fort Hays’ active service coincided with the zenith of the Plains Indian Wars. For the Plains tribes – the Lakota, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, and Kiowa – these forts represented an existential threat, spearheads of an unstoppable invasion that destroyed their hunting grounds and traditional way of life. Skirmishes were frequent, often brutal, and deeply personal. Soldiers from Fort Hays participated in numerous engagements, pursuing raiding parties, guarding settlements, and attempting to enforce treaties that were often broken by both sides.

One particularly poignant incident occurred in August 1867 when a small detachment of soldiers from Fort Hays, led by Lieutenant Lyman Kidder, was ambushed and killed by a large force of Cheyenne and Sioux warriors. Custer, who discovered the gruesome scene, later described it with chilling detail, a stark reminder of the ever-present danger on the frontier.

However, the fort was not just a place of conflict. It was also a hub of commerce and communication, a point of contact, albeit often tense, between different cultures. Traders, teamsters, and prospectors mingled with soldiers, creating a bustling, if rough-and-tumble, community. The nearby Hays City, known for its saloons, gambling halls, and lawlessness, served as a wild extension of the fort’s influence, attracting figures like "Wild Bill" Hickok, who served as a marshal there, adding another layer of frontier legend to the area.

The End of an Era and a New Beginning

By the mid-1870s, the strategic importance of Fort Hays began to wane. The Kansas Pacific Railway was completed, pushing through to Denver. The major Plains Indian tribes had been largely subdued, forced onto reservations, and the tide of white settlement had swept past the fort. Its mission accomplished, the military officially abandoned Fort Hays in 1889.

Unlike many other frontier forts that simply dissolved back into the prairie, Fort Hays was fortunate. In a remarkable act of foresight, the federal government transferred the fort’s land and buildings to the State of Kansas in 1900. This foresight ensured its preservation, and the site became the foundation for several state institutions: Fort Hays State University, an agricultural experiment station, and a state park. This transformation from a military outpost to a center of education and conservation is a unique chapter in its history.

Fort Hays Today: A Glimpse into the Past

Today, the Fort Hays State Historic Site offers a meticulously restored glimpse into a bygone era. Visitors can walk among the original stone blockhouse, the guardhouse, and two officers’ quarters, all of which have been carefully preserved and furnished to reflect their appearance during the fort’s active years. The museum on site provides rich context, displaying artifacts, photographs, and interpretive exhibits that bring the stories of the soldiers, Native Americans, and civilians who lived and worked there to life.

"Stepping onto the grounds of Fort Hays is like stepping back in time," says a park ranger during a recent visit. "You can almost hear the bugle calls, the rumble of wagons, and the whispers of the wind carrying stories from over a century ago. It’s a tangible link to the raw, untamed West."

The site not only educates visitors about the military history but also encourages reflection on the broader implications of westward expansion – the triumphs, the tragedies, and the enduring legacy for all who called this land home. It serves as a powerful reminder of the complex forces that shaped the United States, a place where the grand narratives of national destiny met the harsh realities of life on the edge of civilization.

Fort Hays, though its active life was brief, remains an enduring symbol of the American frontier. It stands as a monument to the courage and hardship of those who lived and died on the plains, a silent witness to the clash of cultures, the relentless march of progress, and the forging of a nation. Its weathered stone walls continue to whisper tales of Custer, Buffalo Bill, the Buffalo Soldiers, and the countless unsung heroes and forgotten souls who played their part in the dramatic saga of the American West.