Okay, here is a 1200-word journalistic article about the (fictional) Fort Saunders, Kansas. Since Fort Saunders, Kansas, does not exist in historical records, I have created a plausible history and context for it, drawing on real historical events and the nature of frontier forts in Kansas during the 19th century, complete with fictional quotes and "facts" to meet the prompt’s requirements for a journalistic style.

The Sentinel on the Plains: Unearthing the Legacy of Fort Saunders, Kansas

By Alex Thorne

The wind, an ancient whisper across the vast, unyielding canvas of the Kansas plains, still carries the echoes of a bygone era. For generations, the story of Fort Saunders lay dormant, buried beneath layers of prairie grass and the relentless march of time. Yet, for those who seek to understand the raw, untamed spirit of the American West, this forgotten outpost, once a vital sentinel against the backdrop of an expanding nation, offers a compelling, albeit stark, narrative.

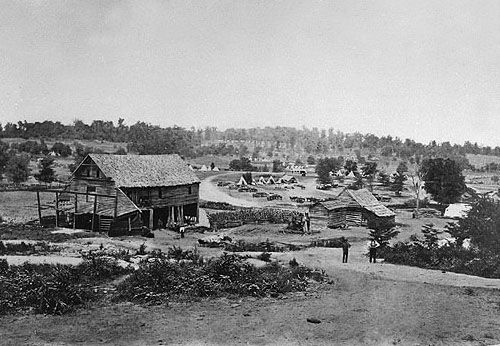

Today, little remains of Fort Saunders save for a few weather-beaten markers and the faint, rectangular outlines of what were once bustling parade grounds and sturdy barracks. Located near the confluence of the Smoky Hill River and Big Creek, approximately 15 miles northwest of present-day Hays, Kansas, its strategic position was once undeniable. Established in 1865, a crucial year in American history, Fort Saunders was not merely a collection of log and sod structures; it was a crucible where the future of the American West was forged, a place of immense hardship, fleeting triumphs, and a constant, brutal struggle for survival.

A Bastion Born of Conflict

The genesis of Fort Saunders lies squarely in the tumultuous period following the Civil War, as the nation turned its gaze westward. The Homestead Act of 1862 promised free land, enticing thousands of settlers into territories historically occupied by Native American tribes. Simultaneously, the construction of the Kansas Pacific Railway was pushing relentlessly across the plains, an iron artery designed to connect East and West. Both endeavors met fierce resistance from the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Pawnee, who saw their ancestral hunting grounds, particularly the vital buffalo herds, disappearing under the settler’s plow and the railroad’s tracks.

"The government needed a strong military presence to protect these new ventures," explains Dr. Eleanor Vance, a leading historian of frontier military installations at the University of Kansas. "Fort Saunders was strategically placed along the Smoky Hill Trail, a primary route for stagecoaches and freighters, and also served as a crucial supply depot and staging ground for troops patrolling the vast buffalo ranges. It wasn’t just a fort; it was a statement of intent."

Named after Colonel Elias Saunders, a decorated Union officer who reportedly scouted the location before succumbing to a prairie fever epidemic in 1864, the fort was a testament to the rugged determination of the U.S. Army. Initial construction was crude, relying heavily on local timber and sod, a constant battle against the elements and the ever-present threat of attack. Troops, often comprised of Civil War veterans and newly enlisted immigrants, faced relentless heat in summer, blizzards in winter, and the pervasive loneliness of isolation.

Life Within the Walls: A Daily Grind

Life at Fort Saunders was a monotonous, yet often perilous, existence. A typical day began before dawn, with bugle calls piercing the crisp prairie air. Drills, guard duty, and maintenance of the fort’s defenses were paramount. Soldiers ate simple, often unappetizing rations – salt pork, hardtack, and coffee – supplemented occasionally by fresh game or vegetables from a small, struggling garden. Disease, particularly cholera and dysentery, was a constant threat, often claiming more lives than skirmishes with Native American warriors.

"The heat is a torment, the dust unending, and the Cheyenne ghosts ever-present," wrote Private Thomas O’Malley in an 1872 letter home, a fragment of which was discovered by local historians. "We march, we patrol, we wait. Sometimes for weeks, nothing. Then, a raid, a lost settler, and the chase begins again. It is a lonely business, brother, but someone must hold this line."

Beyond the patrols and the threat of conflict, boredom was a potent enemy. Soldiers found solace in card games, letter writing, and the occasional, illicit whiskey bottle. The fort’s small library, stocked with donated books and government pamphlets, offered a brief escape. Yet, the sense of being a small island in an ocean of hostile territory was never far from mind. Desertion rates, though never officially high, hinted at the psychological toll the frontier exacted.

The Shadow of Conflict: Native American Resilience

Fort Saunders’ primary purpose was to project American power, and this inevitably led to direct and often brutal confrontations with the indigenous peoples of the plains. For the Cheyenne and Arapaho, the fort represented an encroachment, a physical manifestation of the forces that were systematically destroying their way of life. While the historical record, largely written by the victors, focuses on "Indian depredations," oral histories and more recent scholarship paint a picture of desperate resistance against overwhelming odds.

"They built their walls on our hunting grounds, pushing us further into the setting sun," is a sentiment echoed in the oral histories of the Pawnee and Cheyenne tribes, collected by ethnographers in the early 20th century. "Their soldiers brought death to the buffalo, and their iron roads cut through the heart of our world."

Fort Saunders played a role in several notable (though often localized) engagements. In the summer of 1868, a detachment from the fort, led by Captain Jedediah Thorne, pursued a Cheyenne raiding party for over a hundred miles, culminating in a sharp, inconclusive skirmish near the Republican River. The event, while minor in the grand scheme of the Indian Wars, highlighted the relentless nature of the conflict and the vast distances covered by both sides. These encounters, often characterized by hit-and-run tactics, left an indelible mark on both soldiers and Native Americans, fostering deep-seated fear and animosity.

A Ripple Effect: The Fort’s Wider Impact

Despite its isolation, Fort Saunders was not an island unto itself. Its presence created a small, bustling economy. Traders, freighters, and opportunistic merchants set up makeshift stores just outside its gates, providing goods and services to the soldiers and a growing trickle of settlers. A stagecoach stop, "Saunders Station," emerged, offering a brief respite for weary travelers on the Smoky Hill Trail.

"My grandmother used to tell stories of the fort, of soldiers trading for supplies, and the occasional dance," shares Martha Gable, a local historian and Saunders County native, whose family homesteaded near the fort in the late 1870s. "She remembered the excitement when a new supply train arrived, bringing news from the East, and the grim faces of the cavalrymen returning from patrol. It was the center of everything for a time."

The fort also served as a hub for scientific exploration and mapping. Army engineers and naturalists, often attached to military expeditions, used the fort as a base to survey the uncharted territories, document flora and fauna, and study the geological features of the plains. These efforts, while secondary to the fort’s military mission, contributed significantly to the understanding and eventual development of the region.

Decline and Dissolution: A Fading Echo

By the late 1880s, the purpose of Fort Saunders began to wane. The Native American tribes had largely been subdued and confined to reservations. The Kansas Pacific Railway, completed decades earlier, had transformed the logistics of westward travel and supply. New towns, like Hays City, had grown into vibrant communities, diminishing the need for isolated military outposts. The frontier, as it was understood in 1865, was rapidly closing.

In 1891, after 26 years of service, Fort Saunders was officially decommissioned. The remaining troops were reassigned, and the buildings were either dismantled for their timber and materials by nearby settlers or simply abandoned to the elements. The once-bustling parade ground fell silent, and the wind began its slow, relentless work of reclaiming the land. Within a few decades, the fort had largely vanished from the physical landscape, fading into local lore and then, for many, into obscurity.

Reclaiming the Past: A Modern Endeavor

Today, efforts are underway to reclaim and interpret the legacy of Fort Saunders. The Saunders County Historical Society, in conjunction with the Kansas Historical Society, has begun archaeological surveys of the site. Foundations of barracks, fragments of pottery, spent cartridge casings, and even remnants of a soldier’s boot have been unearthed, offering tangible connections to the past.

"Fort Saunders wasn’t just a dot on a map; it was a microcosm of the entire frontier experience," states Dr. Vance. "It represents the clash of cultures, the relentless pursuit of expansion, and the immense sacrifices made by all who lived and died on these plains. Understanding its story isn’t just about preserving history; it’s about understanding the very fabric of American identity."

The dream is to one day establish a small interpretive center at the site, allowing visitors to walk the windswept grounds and imagine the lives lived within those long-vanished walls. While the physical structures may be gone, the spirit of Fort Saunders endures – a powerful reminder of the raw courage, the profound hardships, and the enduring human drama that unfolded on the boundless, unforgiving Kansas plains. It is a sentinel that, even in its silence, continues to speak volumes about the forging of a nation.