Echoes in the Earth: The Enduring Legacy of Muscogee (Creek) Nation Lands

The soil remembers. Beneath the sprawling pecan groves of Oklahoma, and deep within the red clay of Alabama and Georgia, lies a memory woven into the very fabric of the land. It is the memory of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, a vibrant and powerful confederacy whose historical lands once stretched across a vast swathe of the American Southeast. This is not merely a story of property, but of profound connection – spiritual, cultural, and political – to a homeland that was systematically stripped away, yet whose legacy continues to shape the identity and future of the Muscogee people.

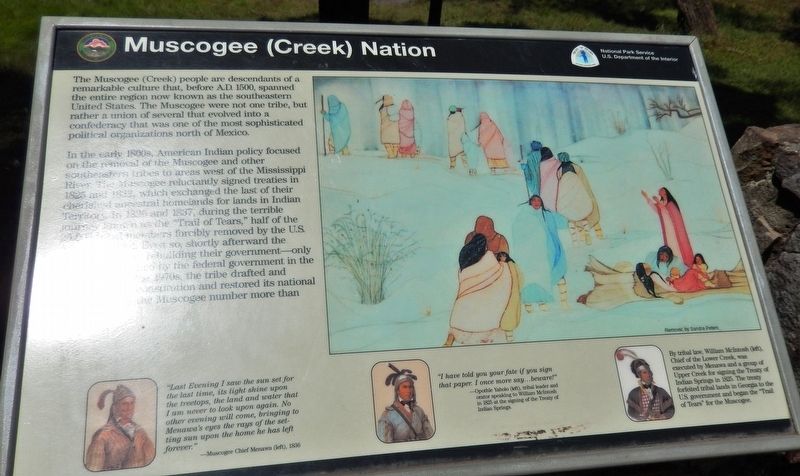

For centuries before European contact, the Muscogee Confederacy thrived across what is now Alabama, Georgia, parts of Florida, Tennessee, and Mississippi. This was a sophisticated society, organized into autonomous towns and clans, united by language, kinship, and a shared cosmology. Their lands were not just territory; they were the source of life, spirituality, and identity. The rivers – the Coosa, Tallapoosa, Flint, and Chattahoochee – were their highways, their fishing grounds, and sacred arteries. The fertile valleys yielded abundant corn, beans, and squash, while the forests provided game and medicinal plants.

"Our land was everything to us," explains Elder Thomas King, a Muscogee historian, reflecting on the ancestral domain. "It was our church, our store, our school. Every tree, every stream, every hill had a name, a story. It was where our ancestors were buried, where our ceremonies were held. It was the physical manifestation of our sovereignty."

The Muscogee people were innovators in agriculture, politics, and warfare. Their confederacy was a model of inter-town cooperation and diplomacy, capable of fielding formidable warriors when necessary, but often preferring negotiation. They built impressive mound complexes, testaments to their organized labor and spiritual reverence, many of which still stand today, silently testifying to a forgotten grandeur.

The arrival of European settlers, however, brought an inexorable shift. Initially, trade relationships flourished, but as the 18th century wore on, the demand for land grew insatiable. The burgeoning American republic, fueled by the doctrine of Manifest Destiny and the explosion of the cotton industry, cast covetous eyes on the rich agricultural lands of the Muscogee.

The early 19th century marked a turning point. The Creek War of 1813-1814, a complex conflict often viewed as a proxy war within the larger War of 1812, pitted Muscogee factions against each other and against American forces led by Andrew Jackson. The decisive Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814 shattered Muscogee military power and led to the punitive Treaty of Fort Jackson. This treaty, signed under duress, forced the Muscogee to cede 23 million acres – more than half of their ancestral lands – to the United States. It was a staggering loss, setting a precedent for further, relentless land cessions.

"The Treaty of Fort Jackson was a wound that never truly healed," says Dr. Cynthia Clark, a scholar of Native American history. "It wasn’t just land; it was an amputation of their economic base, their cultural heartland. It laid the groundwork for the ‘Indian Removal’ policy that would follow."

Despite attempts by some Muscogee leaders to adapt and assimilate, establishing written laws and even adopting elements of American governance, the pressure intensified. The discovery of gold in Georgia on Muscogee lands only exacerbated the desire for their removal. In 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, legislating the forced displacement of the Five Civilized Tribes (Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole) from their ancestral homes in the Southeast to "Indian Territory" west of the Mississippi River, in what is now Oklahoma.

The Muscogee people endured multiple forced removals, culminating in the devastating "Trail of Tears" of 1836. Driven from their homes by federal troops and state militias, often at bayonet point, thousands were marched hundreds of miles in brutal conditions, many dying from disease, starvation, and exposure. It’s estimated that over 3,500 of the 15,000 Muscogee who were forcibly removed perished on this journey. Families were separated, ancient ties to the land severed, and a civilization uprooted.

"My great-great-grandmother walked that trail," shares Muscogee citizen Sarah Jones, her voice heavy with emotion. "She spoke of the cold, the hunger, and the constant fear. But she also spoke of the resilience, the way they held onto their songs and stories, even as they buried their dead along the path. That spirit, that determination to survive, is what we carry today."

Upon arrival in Indian Territory, the Muscogee, like other removed tribes, began the arduous process of rebuilding. They re-established their government in Okmulgee, creating a new capital and attempting to reconstruct their lives and communities. They adopted a written constitution, built schools, and cultivated new farms. Yet, peace remained elusive. The American Civil War divided the Muscogee Nation, leading to further internal conflict and devastation.

The post-Civil War era brought another wave of land loss. The Dawes Act of 1887 and the Curtis Act of 1898 mandated the allotment of tribal lands into individual parcels, a policy designed to break up communal land ownership and facilitate the sale of "surplus" lands to non-Natives. This policy, combined with the dissolution of tribal governments in preparation for Oklahoma statehood in 1907, resulted in the loss of millions more acres of Muscogee land, fragmenting their communities and eroding their sovereignty once again.

For decades, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, like many tribes, fought to reclaim its standing and protect its remaining land base. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 offered a limited opportunity for tribal self-governance, allowing the Muscogee to adopt a new constitution and re-establish some control over their affairs. However, the legacy of broken treaties and land dispossession continued to cast a long shadow.

Then, in a landmark decision in July 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court, in McGirt v. Oklahoma, affirmed that a vast portion of eastern Oklahoma, including the city of Tulsa, remains an Indian reservation for purposes of federal criminal law. The ruling, which centered on the historical boundaries of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation reservation, sent shockwaves across the state and the nation. It effectively recognized that the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s reservation, as defined by treaties from the 19th century, was never disestablished by Congress.

"The McGirt decision was monumental," states Principal Chief David Hill of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. "It wasn’t about taking land from anyone, but about affirming our sovereignty and the solemn promises made in treaties. It reminds everyone that we are still here, our nation is still here, and our historical lands, while altered, still define who we are as a people."

The implications of McGirt are profound, extending beyond criminal jurisdiction to issues of taxation, environmental regulation, and economic development. It has spurred renewed interest in tribal history, treaty law, and the ongoing relationship between tribal nations and the federal and state governments. For the Muscogee, it is a powerful validation of their enduring nationhood and a testament to their ancestors’ foresight and resilience.

Today, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation is a vibrant, self-governing entity with a population of over 90,000 citizens. Based in Okmulgee, Oklahoma, the Nation operates a diverse array of businesses, including casinos, health clinics, and cultural centers, contributing significantly to the state’s economy. They are dedicated to revitalizing their Muscogee language, preserving traditional ceremonies, and educating future generations about their rich history and cultural heritage.

The connection to land, though physically displaced for many, remains central to Muscogee identity. Annual pilgrimages are made to ancestral sites in the Southeast, and efforts are underway to protect sacred grounds that lie beyond their current Oklahoma borders, such as Hickory Ground in Alabama, a ceremonial site forcibly taken and only recently returned to the Muscogee (Creek) Nation.

The story of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s historical lands is a powerful narrative of loss, resilience, and enduring sovereignty. It is a reminder that land is more than just real estate; it is the repository of memory, culture, and identity. As the Muscogee people continue to navigate the complexities of the 21st century, the echoes of their ancestral lands resonate, guiding their path forward and affirming their unbreakable bond with the earth that remembers.