The Ancient Rhythms of the River: Unraveling Salish Traditional Fishing Wisdom

VANCOUVER, BC – The Pacific Northwest, a land of verdant forests, snow-capped peaks, and an intricate network of rivers and estuaries, has for millennia been home to the Salish peoples. For these Indigenous communities, the waters were not merely a resource but the very arteries of life, teeming with a bounty that sustained their societies, shaped their cultures, and defined their spiritual connection to the land. Central to this existence was an unparalleled mastery of fishing, a sophisticated system of knowledge, technology, and reverence that speaks volumes about sustainable living long before the concept entered modern lexicon.

Step back in time, and you’d witness a vibrant tapestry of human ingenuity intertwined with the natural world. From the Coast Salish of what is now British Columbia and Washington State to the Interior Salish nestled amidst the Rocky Mountains, fishing wasn’t just a means of subsistence; it was an intricate dance with the seasons, a communal endeavor, and a profound expression of identity.

"Our ancestors didn’t just ‘fish’," explains Elder Mary Point of the Musqueam Nation, her voice echoing generations of wisdom. "They lived with the fish, understood their cycles, their needs. Every cast, every trap, every net was an act of respect, a prayer for the abundance to continue." This deep understanding, often referred to as Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), is the bedrock of Salish fishing practices, a science refined over thousands of years of observation and intergenerational transfer.

Engineering with Nature: The Ingenuity of Weirs and Traps

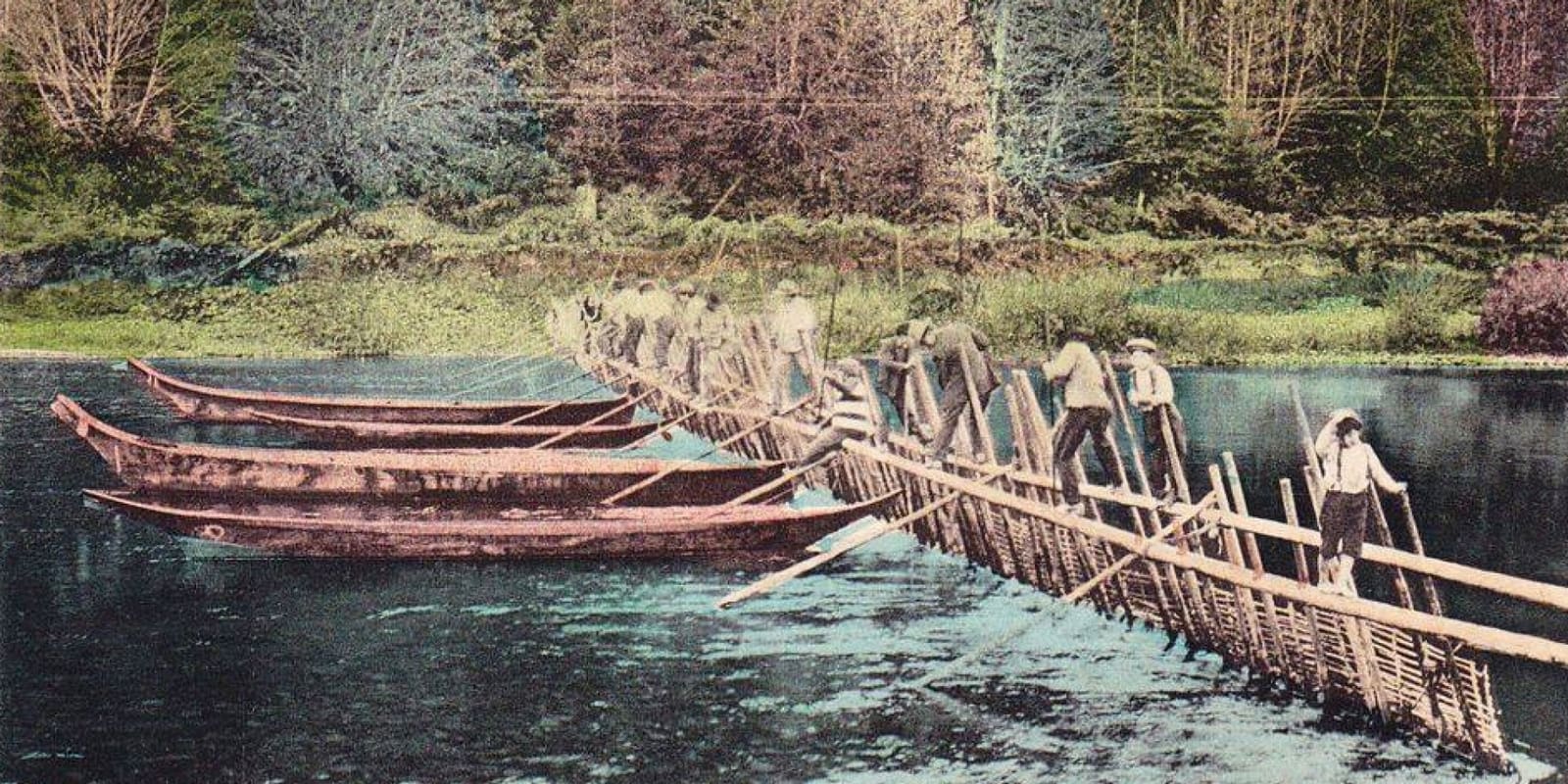

Among the most impressive feats of Salish engineering were the sophisticated fish weirs and traps. These structures, often spanning entire rivers or sections of estuaries, were not brute force barriers but cleverly designed systems that channeled fish into holding pens or capture areas. Built from sturdy stakes, woven branches, and stone, they were designed to be selective, allowing smaller fish or specific species to pass through, ensuring future runs.

For the Coast Salish, particularly adept at harvesting the five species of Pacific salmon, these weirs were colossal undertakings, requiring immense communal effort and precise timing. "Imagine hundreds of people working together, shaping the river," says Dr. John R. McMillan, a fisheries biologist who has studied traditional methods. "These weren’t just fences; they were hydrological marvels, designed to manage water flow and fish movement with incredible precision."

Interior Salish peoples, like the Secwepemc and Okanagan, also employed weirs, often in conjunction with basket traps at strategic points like waterfalls or rapids. These traps, woven from willow or cedar bark, would funnel migrating salmon or steelhead into confined spaces where they could be easily gaffed or netted. The ingenuity lay in their efficiency and their impermanence; many structures were designed to be easily dismantled after the run, minimizing long-term impact on the riverbed and allowing fish passage outside the harvesting season.

The Art of the Net: Reef Nets, Dip Nets, and Seines

Beyond fixed structures, Salish peoples developed a diverse array of netting techniques, each tailored to specific fish species, water conditions, and community needs. Perhaps the most iconic and complex was the reef net fishery, practiced by some Coast Salish groups. This highly cooperative method involved anchoring two canoes offshore, between which a large, wedge-shaped net was submerged. Divers would observe the salmon swimming over a natural or artificial reef (often made of white stone or shell to mimic a spawning ground), and at the signal, the net would be quickly raised, trapping the fish.

"The reef net wasn’t just a fishing technique; it was a societal structure," notes anthropologist Dr. Dale Croes. "It required incredible coordination, trust, and shared knowledge within and between families. It symbolized the interconnectedness of their society and their environment." The catch was distributed according to a strict protocol, ensuring everyone in the community benefited.

Dip nets, often attached to long poles, were common in areas with strong currents or rapids where fish naturally congregated, such as Celilo Falls on the Columbia River. These agile tools allowed individual fishers to deftly scoop salmon as they struggled upstream. Seine nets, large nets pulled through the water to encircle fish, and gill nets, designed to entangle fish by their gills, were also part of the Salish toolkit, albeit often made from natural fibers like nettle, cedar bark, or even kelp, before the introduction of modern materials.

Spears, Harpoons, and Lines: Tools of Precision

For individual hunting, or targeting larger fish like halibut or sturgeon, spears and harpoons were the preferred implements. Salish harpoons were marvels of design, featuring toggling heads that would detach from the shaft once embedded in the fish, remaining secured by a line to a float or the canoe. This design prevented the fish from escaping and allowed the harpooner to play the fish until it was subdued. Spear fishing, often done at night by torchlight, required immense skill and patience.

Hooks and lines, though seemingly simpler, were also employed. Hooks were fashioned from bone, wood, or shell, and lines from twisted plant fibers. These were particularly effective for bottom-dwelling species or for jigging for eulachon (candlefish), a small, oily fish that arrived in immense numbers in early spring and was prized for its rich oil, used as a food source, medicine, and trade item.

Beyond the Catch: Sustainability, Culture, and Economy

What truly set Salish fishing methods apart was the intrinsic ethic of sustainability. They understood that their prosperity depended on the health of the fish populations. Practices like selective harvesting, respecting spawning grounds, allowing escapement (fish to pass upstream to spawn), and the seasonal rotation of fishing sites were deeply embedded.

"We always took only what we needed, and we always thanked the fish," explains Elder Point. "The first fish of the season was celebrated, never sold. It was about gratitude and ensuring the generations to come would also have this bounty." This reciprocal relationship, where humans gave thanks and stewardship in exchange for nature’s gifts, permeated every aspect of their lives.

Fishing was also the engine of the Salish economy and social structure. The abundant catches, especially salmon, allowed for significant surpluses that could be preserved through smoking and drying. This preserved food became a vital trade commodity, facilitating extensive networks across the region, and supported elaborate social gatherings like the Potlatch, where wealth was distributed and social bonds reinforced.

Enduring Legacy: Challenges and Resilience

The arrival of European settlers brought profound disruption to these ancient practices. Dams blocked migratory routes, industrial logging destroyed spawning habitats, and commercial overfishing by non-Indigenous fishers decimated once-plentiful runs. Colonial laws often criminalized traditional fishing methods and restricted Indigenous access to their ancestral territories and resources.

Despite these immense pressures, Salish peoples have fought tirelessly to protect and revitalize their fishing traditions. Landmark legal battles, such as the 1974 Boldt Decision in the United States, affirmed treaty-reserved fishing rights, recognizing Indigenous peoples as co-managers of the resource. Today, Indigenous communities are at the forefront of conservation efforts, blending TEK with Western science to restore habitats and manage fisheries sustainably.

Youth are increasingly engaged in learning the ancient ways, participating in cultural fishing camps where Elders pass down knowledge of net weaving, canoe handling, and the spiritual protocols associated with the harvest. "When I’m out on the water, pulling up a net with my family, I feel connected to something ancient, something strong," says Liam, a young Squamish Nation member. "It’s not just about food; it’s about our identity, our language, our future."

The rhythms of the river continue to pulse through the heart of Salish communities. While the challenges are immense – from climate change impacting salmon runs to ongoing battles for jurisdiction – the wisdom embedded in their traditional fishing methods offers invaluable lessons for all of humanity. It is a powerful reminder that true sustainability comes not from domination, but from a profound understanding, respect, and reciprocal relationship with the natural world, a relationship forged over millennia and vital for the future. The ancient nets may be woven anew, but the spirit of the harvest, and the deep connection to the life-giving waters, remains as strong as ever.