The Crucible of Liberty: A Timeline of the American Revolution

The American Revolution, a seismic upheaval that redrew the map of North America and fundamentally reshaped global political thought, was not a sudden explosion but a slow burn, fueled by simmering grievances and ignited by a series of pivotal events. It was a struggle for self-determination, a testament to the power of ideas, and a crucible that forged a new nation. From the first rumblings of discontent to the final victory, the timeline of this revolution is a dramatic narrative of courage, sacrifice, and the relentless pursuit of liberty.

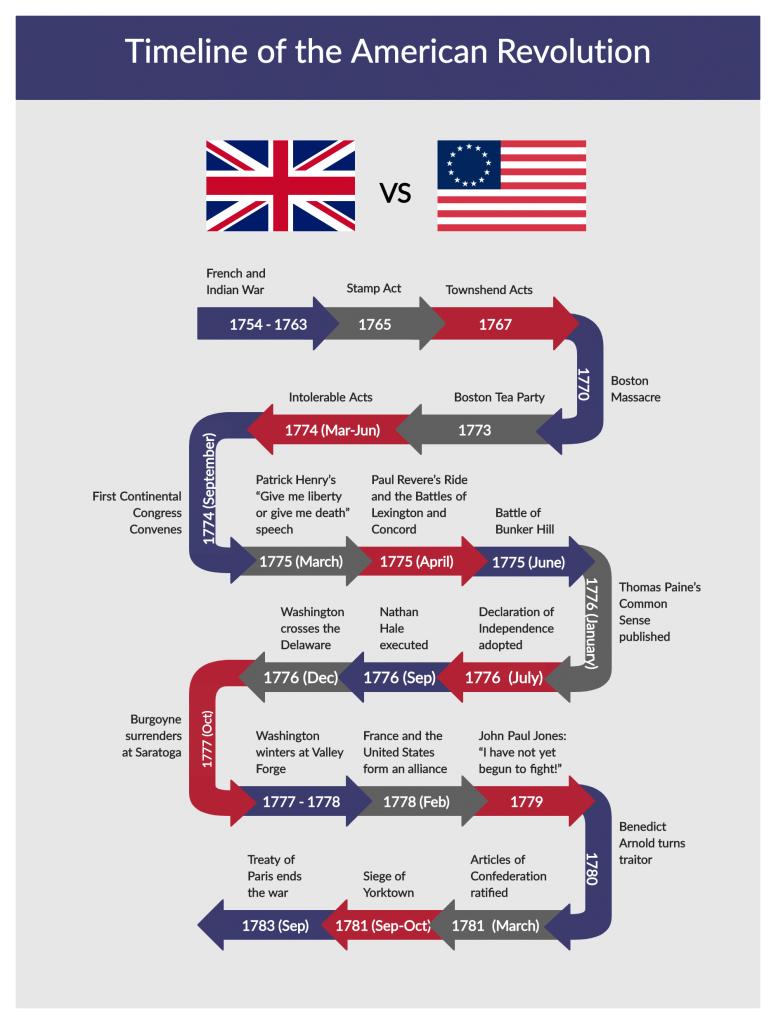

1754-1763: The Seeds of Discontent – The French and Indian War (Seven Years’ War)

While seemingly unrelated, the French and Indian War, fought between Great Britain and France over colonial territory in North America, laid the crucial groundwork for the Revolution. Britain emerged victorious, gaining vast new territories, but at a tremendous cost. The war doubled Britain’s national debt, prompting Parliament to seek new revenue streams from its American colonies, which had largely been left to govern themselves under a policy of "salutary neglect." The colonists, who had fought alongside British regulars, felt a growing sense of identity distinct from their European counterparts and resented the idea of being taxed without direct representation.

1763: The Proclamation of 1763

In an attempt to prevent further costly conflicts with Native American tribes, the British government issued the Proclamation of 1763, forbidding colonial settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains. While intended to maintain peace, it infuriated colonists who saw it as an infringement on their right to expand and a betrayal of their wartime efforts. Land speculation, a major economic driver, was suddenly curtailed.

1764: The Sugar Act

The first direct attempt by Parliament to raise revenue from the colonies, the Sugar Act, imposed duties on sugar, molasses, coffee, and other goods. While it actually lowered the duty on molasses, it aimed to enforce collection more rigorously and crack down on smuggling. This marked a significant shift in British policy, moving from regulating trade to raising revenue, sparking widespread colonial protests and the famous cry, "No taxation without representation."

1765: The Stamp Act

This act proved to be a watershed moment. The Stamp Act mandated that all legal documents, commercial contracts, newspapers, pamphlets, and even playing cards carry a tax stamp. It was a direct, internal tax on virtually every piece of paper used in the colonies. The reaction was swift and fierce. Colonial assemblies passed resolutions condemning it, merchants organized boycotts, and secret societies like the Sons of Liberty formed to intimidate stamp distributors. Patrick Henry, a young lawyer from Virginia, famously declared before the House of Burgesses, "If this be treason, make the most of it!" The Stamp Act was repealed in 1766 due to overwhelming colonial resistance and economic pressure from British merchants.

1767: The Townshend Acts

Despite the repeal of the Stamp Act, Parliament, asserting its right to legislate for the colonies "in all cases whatsoever" (the Declaratory Act of 1766), soon passed the Townshend Acts. These acts imposed duties on imported goods like glass, lead, paints, paper, and tea, and established new customs boards to enforce collection. The colonists responded with renewed boycotts, particularly of British goods. These acts also allowed for "writs of assistance," general search warrants that permitted customs officials to search colonial homes and businesses without cause, further inflaming tensions over privacy and rights.

1770: The Boston Massacre

As tensions escalated, the presence of British troops in Boston, sent to enforce the Townshend Acts, became a constant source of friction. On March 5, 1770, a crowd of colonists confronted a small contingent of British soldiers. Taunts and projectiles (snowballs, stones) escalated into violence, and the soldiers fired into the crowd, killing five colonists, including Crispus Attucks, a man of African and Native American descent, often considered the first casualty of the Revolution. The "Boston Massacre," though a relatively small incident, was widely publicized by figures like Samuel Adams and Paul Revere as an act of British tyranny, fueling anti-British sentiment.

1773: The Tea Act and the Boston Tea Party

After the repeal of most Townshend duties (except for the tax on tea), a period of relative calm ensued. However, in 1773, Parliament passed the Tea Act, designed to save the struggling British East India Company by granting it a monopoly on tea sales in the colonies and allowing it to sell tea directly, bypassing colonial merchants. While it actually made tea cheaper, colonists saw this as a sly maneuver to trick them into accepting the principle of parliamentary taxation. On December 16, 1773, in an audacious act of defiance, a group of Sons of Liberty, disguised as Mohawk Indians, boarded three British ships in Boston Harbor and dumped 342 chests of tea into the water – an estimated £10,000 worth of tea. This act of protest, the Boston Tea Party, sent shockwaves through the British Empire.

1774: The Intolerable Acts (Coercive Acts) and the First Continental Congress

Britain’s response to the Boston Tea Party was punitive. Parliament passed a series of measures known as the Coercive Acts (dubbed the "Intolerable Acts" by the colonists). These acts closed Boston Harbor until the destroyed tea was paid for, revoked Massachusetts’ charter, allowed British officials accused of crimes to be tried in Britain, and expanded the Quartering Act, requiring colonists to house British soldiers. Far from isolating Massachusetts, these acts galvanized the other colonies.

In response, delegates from twelve of the thirteen colonies (Georgia did not attend) convened in Philadelphia in September 1774 for the First Continental Congress. They called for a complete boycott of British goods, asserted their rights as Englishmen, and urged each colony to form militias, signaling a unified resolve against British policies.

1775: The Shot Heard ‘Round the World – Lexington and Concord

The stage was set for armed conflict. On April 19, 1775, British troops marched from Boston to Concord, Massachusetts, intending to seize colonial arms and arrest revolutionary leaders Samuel Adams and John Hancock. Paul Revere, William Dawes, and Samuel Prescott rode to warn the militia. At Lexington Green, a confrontation erupted between colonial minutemen and British soldiers. A shot was fired – its origin unknown – sparking the first skirmish of the Revolution. The British proceeded to Concord but found most of the arms already moved. On their retreat back to Boston, they were harried by colonial militias, suffering significant casualties. Ralph Waldo Emerson would later immortalize this event as "the shot heard ’round the world," marking the official start of the war.

1775: The Second Continental Congress and Bunker Hill

In May 1775, the Second Continental Congress convened, effectively becoming the governing body of the rebellious colonies. They established the Continental Army and appointed George Washington, a Virginian with military experience from the French and Indian War, as its commander-in-chief.

On June 17, 1775, the Battle of Bunker Hill (actually fought on Breed’s Hill) took place. Though a tactical victory for the British, who eventually dislodged the entrenched American forces, it came at a tremendous cost, demonstrating the fierce determination of the colonial militia. The British suffered over 1,000 casualties, significantly more than the Americans.

1776: Common Sense and the Declaration of Independence

As the war progressed, the idea of complete independence from Britain gained traction. Thomas Paine’s pamphlet, Common Sense, published in January 1776, played a pivotal role. Written in clear, accessible language, it passionately argued for American independence, denouncing monarchy and advocating for a republican government. It became an instant bestseller, swaying public opinion towards separation.

On July 2, 1776, the Continental Congress voted to approve Richard Henry Lee’s resolution for independence. Two days later, on July 4, 1776, they formally adopted the Declaration of Independence, primarily authored by Thomas Jefferson. This document articulated the philosophical underpinnings of the new nation, asserting the unalienable rights to "Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness" and listing grievances against King George III. It was a revolutionary statement, declaring the birth of the United States of America.

1776-1777: Early Setbacks and Crucial Victories

The early years of the war were challenging for the Continental Army. Washington’s forces suffered major defeats in the New York Campaign (Battle of Long Island, White Plains) and were forced into a desperate retreat through New Jersey. Morale plummeted. However, Washington orchestrated two brilliant and daring winter victories. On Christmas night, 1776, he famously crossed the Delaware River and surprised Hessian mercenaries at Trenton, New Jersey. A week later, he secured another victory at Princeton. These triumphs, though small in scale, dramatically boosted American morale and kept the cause of independence alive.

1777: The Battle of Saratoga – A Turning Point

In October 1777, the American forces achieved a decisive victory at the Battle of Saratoga, New York. British General John Burgoyne’s invasion force, attempting to cut off New England from the other colonies, was surrounded and forced to surrender. This victory was the single most important turning point of the war. It convinced France, a long-time rival of Britain, that the American cause was viable, leading to a formal alliance in 1778. French financial aid, military supplies, and naval power would prove indispensable to the American victory.

1777-1778: Valley Forge

Despite the triumph at Saratoga, the winter of 1777-1778 was a period of immense suffering for the Continental Army at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. Enduring brutal cold, disease, and starvation, thousands of soldiers died or deserted. Yet, under Washington’s steadfast leadership and the training of Prussian Baron von Steuben, the army emerged in the spring as a more disciplined and professional fighting force, forged in the crucible of hardship.

1778-1781: The War in the South and Shifting Strategies

With French entry, the war became a global conflict. Britain shifted its strategy, focusing on the Southern colonies, where they believed Loyalist support was stronger. Battles like Charleston (a British victory), Cowpens (an American victory), and Guilford Courthouse (a costly British victory) characterized this phase. The fighting was often brutal, marked by guerrilla warfare and deep divisions within communities. The defection of American hero Benedict Arnold to the British side in 1780 was a shocking blow, highlighting the psychological toll of the prolonged conflict.

1781: The Siege of Yorktown – The Decisive Blow

The culmination of the war came in the autumn of 1781. General Washington, coordinating with French General Rochambeau and the French fleet under Admiral de Grasse, executed a brilliant maneuver. They secretly marched their combined forces south to Virginia, trapping British General Cornwallis’s army at Yorktown. The French navy blockaded the Chesapeake Bay, preventing British naval reinforcement or escape by sea. After a three-week siege, Cornwallis, with no hope of relief, was forced to surrender his entire army on October 19, 1781. This decisive victory effectively ended major fighting in the American Revolution.

1783: The Treaty of Paris

Though fighting largely ceased after Yorktown, formal peace negotiations took time. The Treaty of Paris, signed on September 3, 1783, officially ended the war. Great Britain formally recognized the independence of the United States of America. The treaty also established the generous boundaries of the new nation, stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to the Mississippi River and from Canada to Florida.

The Legacy

The American Revolution was more than just a struggle for independence; it was a profound ideological transformation. It established the principle of popular sovereignty, that government derives its just powers from the consent of the governed. It inspired revolutions and independence movements worldwide for centuries to come. From a collection of disparate colonies, a nation was born, founded on radical ideals of liberty, equality, and self-governance – a legacy that continues to shape its identity and influence the world. The timeline of its birth is a testament to the enduring power of the human spirit to fight for freedom.