The Pen That Forged a Nation: Unpacking America’s Declaration of Independence

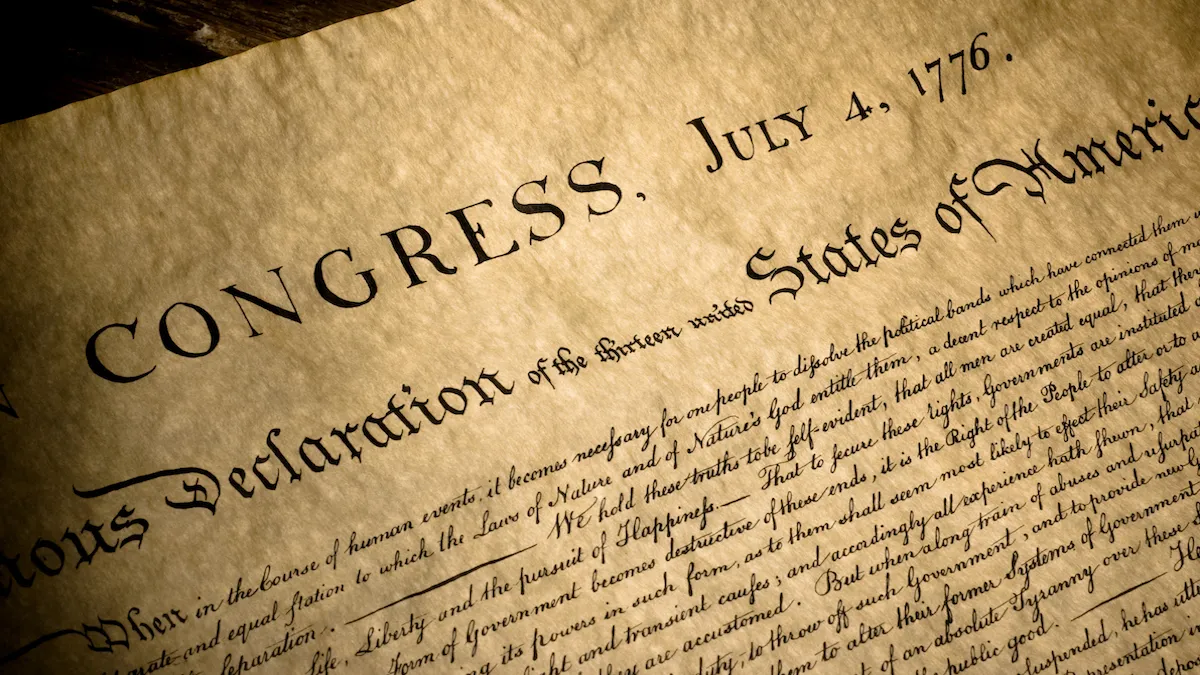

On a sweltering summer day in Philadelphia, over two centuries ago, a document was penned that would forever alter the course of human history. More than a mere declaration of war or a list of grievances, the American Declaration of Independence, adopted on July 4, 1776, was a radical articulation of universal human rights, a philosophical blueprint for self-governance, and a defiant roar against tyranny. It was, and remains, a living testament to the power of ideas and the unyielding human desire for liberty.

To understand the Declaration, one must first grasp the turbulent epoch from which it emerged. For over a decade, tensions had been escalating between Great Britain and its thirteen American colonies. Following the costly Seven Years’ War (known as the French and Indian War in America), Parliament sought to recoup its expenses by imposing a series of taxes on the colonies – the Stamp Act, the Townshend Acts, the Tea Act – without their consent or representation. The rallying cry, "No taxation without representation," encapsulated the core of the colonists’ burgeoning resentment.

These economic grievances were merely the surface. Beneath lay a deeper current of philosophical awakening. The Enlightenment, a powerful intellectual movement sweeping across Europe, had profoundly influenced American thinkers. Philosophers like John Locke, with his theories on natural rights – life, liberty, and property – and the social contract, provided the intellectual ammunition for the colonial cause. The idea that government derived its just powers from the consent of the governed, and that people had a right to revolt against oppressive rule, became the bedrock upon which the Declaration would stand.

The Road to Independence

By the spring of 1776, the idea of reconciliation with Britain seemed increasingly futile. Battles had been fought at Lexington and Concord, Bunker Hill, and Boston. King George III had declared the colonies in a state of rebellion, and British troops, including Hessian mercenaries, were being dispatched. Thomas Paine’s fiery pamphlet, "Common Sense," published in January 1776, galvanized public opinion, arguing forcefully for complete separation and the establishment of an independent republic. "The cause of America is in a great measure the cause of all mankind," Paine famously declared, articulating a universal vision.

On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia introduced a resolution in the Continental Congress, stating, "That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved." This bold proposition ignited intense debate. Some delegates, still clinging to hope for reconciliation, hesitated. Others, particularly those from the southern colonies, worried about the potential for social upheaval and the implications for slavery.

Recognizing the need for a formal justification, the Congress appointed a "Committee of Five" on June 11, 1776, to draft a statement of independence. The committee comprised John Adams of Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, Robert R. Livingston of New York, and the youngest, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia. Despite Adams’s significant contributions to the cause and his keen intellect, it was the eloquent and erudite Jefferson who was tasked with penning the initial draft.

Jefferson’s Pen: A Masterpiece of Eloquence

Jefferson, then only 33, retreated to his rented rooms in Philadelphia and, over the course of about two weeks, crafted a document that would become a cornerstone of democratic thought. Drawing heavily on Enlightenment principles, particularly Locke’s ideas, and incorporating existing colonial declarations of rights, Jefferson produced a text of remarkable clarity and power.

The Declaration is structured in five distinct parts:

- The Introduction: A powerful opening statement declaring the necessity for the colonies to explain their separation.

- The Preamble: The most famous and enduring section, setting forth the philosophical foundation of the new nation. It begins with the immortal words: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness." This single sentence encapsulated a revolutionary concept – that rights were inherent, not granted by monarchs or governments, and that the purpose of government was to protect these rights.

- The Body (List of Grievances): A comprehensive and scathing indictment of King George III’s abuses and usurpations. This section details 27 specific complaints, ranging from imposing taxes without consent and quartering troops to obstructing justice and waging war against the colonists. It serves as the "bill of particulars" justifying the right to revolution.

- The Denunciation of the British People: A more subdued section expressing regret that the British people had failed to heed the colonists’ pleas for justice.

- The Conclusion (The Declaration of Independence): The formal and definitive statement of separation. "We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States…" It concludes with the pledge of "our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor."

Debate, Revision, and Adoption

Jefferson’s initial draft was reviewed by Franklin and Adams, who made minor changes. It was then presented to the full Continental Congress on June 28. The ensuing debate was vigorous and intense, lasting for several days. Delegates scrutinized every phrase, every word. One of the most significant changes involved the removal of a clause in which Jefferson condemned King George III for upholding the slave trade, branding it an "execrable commerce" and a "cruel war against human nature." This clause was struck out at the insistence of delegates from Georgia and South Carolina, who relied heavily on slave labor, and with the tacit consent of some Northern delegates whose merchants profited from the trade. This deletion stands as a stark reminder of the nascent nation’s profound hypocrisy, a contradiction that would plague America for generations.

Despite these compromises, the core message remained intact. On July 2, 1776, the Congress voted unanimously in favor of Lee’s resolution for independence. John Adams famously wrote to his wife Abigail, "The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America." He believed this date, marking the actual vote for separation, would be celebrated for generations. However, it was the adoption of the revised Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, that would be etched into the national consciousness.

Though adopted on the 4th, the engrossed (final, calligraphic) copy was not signed until August 2, 1776. Fifty-six delegates eventually affixed their names, an act of immense courage. Each signature was an act of treason against the British Crown, carrying the penalty of death if caught. John Hancock, President of the Congress, famously signed his name in a large, bold hand, reputedly so that "King George can read that without his spectacles." Benjamin Franklin, ever the wit, is said to have remarked, "We must all hang together, or assuredly we shall all hang separately."

Immediate Impact and Enduring Legacy

News of the Declaration spread quickly, read aloud to crowds in town squares, printed in newspapers, and circulated throughout the colonies. It transformed a localized rebellion into a principled struggle for human rights, providing a powerful moral justification for the American Revolution. It was not merely a declaration of political separation but a profound statement of purpose, setting forth the ideals for which the nascent nation would fight.

The Declaration’s influence extends far beyond America’s borders. It became a beacon for revolutionaries and freedom fighters worldwide. Its principles inspired the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in 1789 and numerous independence movements across Latin America in the 19th century. Its core assertion of "unalienable Rights" has resonated in countless struggles against oppression.

Within the United States, the Declaration has served as both an aspirational ideal and a constant challenge. Abolitionists, women’s suffragists, and civil rights leaders have all invoked its sacred words to demand that America live up to its founding promises. Abraham Lincoln, in his Gettysburg Address, famously re-centered the nation on the Declaration’s principle of equality, reminding Americans that the nation was "conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal." A century later, Martin Luther King Jr., in his "I Have a Dream" speech, called the Declaration a "promissory note" that America had yet to fully honor for its Black citizens.

A Living Document

Today, the Declaration of Independence remains a potent symbol of liberty and self-determination. It is not a dusty relic but a living document, continually reinterpreted and debated. Its bold assertion that "all men are created equal" continues to inspire movements for justice, equality, and human dignity around the globe.

While the men who penned and signed it were products of their time, with their own biases and contradictions, the ideals they articulated transcended their immediate circumstances. They laid down a marker, a universal standard against which all governments and societies could be measured. The Declaration of Independence is more than a historical artifact; it is a timeless declaration of human aspiration, a reminder that the pursuit of liberty and equality is an ongoing journey, and that the power to shape our destiny ultimately rests with "the good People." Its words, forged in a moment of desperate courage, continue to echo, challenging each generation to strive for a more perfect union and a more just world.