The Anatomy of Upheaval: Deconstructing the Causes of Revolution

The word "revolution" itself carries a charge, a frisson of both terror and liberation. It evokes images of barricades, mass protests, fallen statues, and the seismic shifts that redefine nations and reshape history. Yet, beneath the dramatic surface of sudden uprising lies a complex web of simmering resentments, structural inequalities, and intellectual currents that coalesce over time. Revolutions are rarely spontaneous; they are the culmination of deep-seated grievances, often ignited by a catalyst that finally breaks the dam of popular patience. To understand these transformative periods is to peer into the very soul of human societies and their unending quest for justice, freedom, or survival.

At its heart, a revolution is a fundamental and often violent change in the political, social, and economic order of a society. It is a rejection of the status quo, an assertion that the existing system is no longer fit for purpose, and that a new one must rise in its place. While each revolution possesses its unique flavour, a close examination reveals recurring patterns and underlying causes that transcend geography and epoch.

The Economic Crucible: When Sustenance Fails

Perhaps the most potent and consistent driver of revolutionary sentiment is economic hardship and inequality. When a significant portion of the populace struggles to meet basic needs – food, shelter, dignity – while a privileged elite prospers, the ground becomes fertile for discontent. This is not merely about poverty in absolute terms, but often about relative deprivation and a perceived injustice in the distribution of wealth.

Consider the French Revolution of 1789. While fueled by Enlightenment ideals, its immediate spark was economic. A series of poor harvests led to soaring bread prices, pushing the urban poor to the brink of starvation. At the same time, the French monarchy and aristocracy lived in lavish excess, exemplified by Versailles, while the state teetered on the brink of bankruptcy. "Let them eat cake," a phrase infamously (and likely apocryphally) attributed to Marie Antoinette, perfectly encapsulates the chasm between the ruling class and the suffering masses. This stark contrast between opulent wealth and widespread hunger created an unbearable tension that exploded into violence.

Similarly, the Russian Revolutions of 1917 were profoundly shaped by economic distress. Years of land hunger among the peasantry, abysmal working conditions in nascent industrial centres, and the catastrophic economic strain of World War I, which led to chronic food shortages and runaway inflation, eroded the Tsar’s authority. As historian Orlando Figes noted in "A People’s Tragedy," "The entire history of Russia could be seen as a series of attempts to resolve the problems of backwardness, and the revolution was only the most violent of them." When soldiers, many of whom were peasants, began to mutiny and workers went on strike, the economic collapse became a direct pathway to political overthrow.

The Shackles of Oppression: Political Disenfranchisement

Beyond economic grievances, the lack of political freedom and representation is a critical factor. When people feel voiceless, powerless, and subject to arbitrary rule, their frustration can build into revolutionary fervor. Authoritarian regimes that suppress dissent, deny basic rights, and perpetuate corruption inevitably sow the seeds of their own destruction.

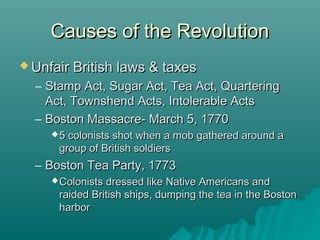

The American Revolution offers a classic example. While not solely economic, the cry of "no taxation without representation" was fundamentally about political power. The colonists felt they were being governed without their consent, their rights as British subjects denied. The Stamp Act, the Townshend Acts, and other punitive measures were seen as infringements on their liberty, leading to a profound belief that the existing political structure was tyrannical and illegitimate. As Thomas Jefferson articulated, "When government fears the people, there is liberty. When the people fear the government, there is tyranny." The American colonists chose liberty.

More recently, the Arab Spring uprisings of 2010-2011 were largely driven by a yearning for political freedom after decades of autocratic rule. In Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, and Syria, entrenched dictatorships suppressed opposition, engaged in rampant corruption, and offered no legitimate channels for political participation. The self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi, a Tunisian street vendor protesting official harassment, became a potent symbol of the indignity and powerlessness felt by millions, sparking a wave of protests demanding democracy, justice, and an end to corruption.

The Unraveling Fabric: Social Injustice and Inequality

Revolutions also frequently erupt from deep-seated social injustices and rigid class structures that deny mobility and dignity to large segments of society. This goes beyond economic disparity to encompass discrimination based on race, religion, caste, or other social identifiers.

The Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) stands as a stark testament to this. It was the only successful slave revolt in history, transforming a French colony built on brutal chattel slavery into the first free black republic. The system of slavery was an extreme form of social injustice, denying enslaved Africans any rights, humanity, or hope. The French Revolution’s ideals of "liberty, equality, fraternity" ironically provided intellectual fuel for the enslaved, who questioned why these principles did not extend to them. Led by figures like Toussaint Louverture, the sheer inhumanity of their condition provided an unparalleled motivation to fight for a new social order.

In Latin America, the wars of independence in the early 19th century, while also driven by political and economic factors, often had a strong undercurrent of social tension between the Peninsulares (Spanish-born elites), Creoles (European-descended but born in the Americas), Mestizos (mixed European and indigenous), and indigenous populations. The rigid social hierarchy of the colonial system, which privileged birth over merit and denied opportunities to the vast majority, fueled resentment and ultimately contributed to the breakdown of Spanish imperial control.

The Spark of Ideas: Intellectual Ferment and Ideological Currents

While grievances provide the fuel, intellectual and ideological currents often provide the blueprint and the rallying cry for revolution. New ways of thinking can challenge the legitimacy of the old order and offer a compelling vision for a different future.

The Enlightenment profoundly influenced the American and French Revolutions. Philosophers like John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Voltaire articulated concepts of natural rights, popular sovereignty, the social contract, and the separation of powers. These ideas undermined the divine right of kings and justified the right of the people to overthrow tyrannical governments. The American Declaration of Independence, with its assertion of "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness," directly reflects Lockean philosophy.

Similarly, the Russian Revolution was deeply influenced by Marxist-Leninist ideology. Karl Marx’s theories of class struggle, the exploitation of the proletariat by the bourgeoisie, and the inevitability of a communist revolution provided a powerful intellectual framework for the Bolsheviks. Lenin adapted these ideas to the Russian context, offering a clear, albeit brutal, path to a new social and economic order that resonated with many workers and peasants desperate for change.

The State’s Decay: Weakness, Incompetence, and Loss of Legitimacy

Even with widespread grievances, a strong and competent state can often suppress revolutionary movements. However, when the state itself begins to decay, losing its legitimacy and capacity to govern effectively, the path to revolution opens wider. This decay can manifest in several ways:

- Financial Collapse: Governments drowning in debt, unable to pay their armies or provide public services, lose credibility. Pre-revolutionary France is a prime example.

- Military Defeat: A humiliating loss in war can expose the state’s weakness, erode national pride, and provide returning, often armed, soldiers with a reason to turn against their own government. Russia’s performance in World War I was a major factor in the collapse of the Tsarist regime.

- Rampant Corruption: When the ruling elite is perceived as self-serving and corrupt, diverting national resources for personal gain, public trust evaporates. This was a major grievance in many Arab Spring countries.

- Loss of Moral Authority: If the government is seen as illegitimate, unjust, or simply incompetent, its decrees lose their power, and people become less willing to obey.

Alexis de Tocqueville, in "The Old Regime and the Revolution," famously observed that revolutions often occur not when conditions are at their worst, but when they are improving, yet expectations are rising faster than the state can deliver. This "revolution of rising expectations" suggests that a government that appears weak or indecisive, even while attempting reforms, can inadvertently embolden revolutionary forces.

The Catalyst and the Crucible: Triggers and Tipping Points

Finally, all these underlying causes often require a catalyst or a specific event to ignite the fuse. This trigger is rarely the cause of the revolution, but rather the "straw that breaks the camel’s back," transforming simmering discontent into open rebellion.

- For the French Revolution, the Storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789, became a powerful symbol of popular defiance against royal authority.

- For the Arab Spring, Mohamed Bouazizi’s self-immolation in Tunisia, filmed and shared widely, became the spark that lit the regional conflagration.

- In Russia, the Bloody Sunday massacre of 1905, where unarmed protestors were shot by imperial guards, irrevocably shattered the myth of the benevolent Tsar, though the actual revolution was years later.

These triggers often occur when a state responds to protest with disproportionate force, or when a perceived minor injustice becomes a symbol of systemic oppression. Modern communication technologies, from printing presses to social media, can rapidly disseminate news of these triggers, mobilizing large numbers of people who were previously isolated in their discontent.

Conclusion: The Enduring Quest for Change

Revolutions, therefore, are not simple events but complex, multi-faceted phenomena arising from a potent brew of economic distress, political oppression, social injustice, and the ferment of new ideas, all occurring against a backdrop of state weakness and culminating in a specific catalytic event. They are a stark reminder that when the social contract between the rulers and the ruled breaks down irreparably, when the mechanisms for peaceful change are blocked, and when the suffering of the many becomes intolerable, the human spirit’s yearning for a better life can unleash a transformative, and often violent, torrent of change.

Understanding these underlying causes is not merely an academic exercise; it offers crucial insights into the fragility of political systems and the enduring human quest for dignity, justice, and self-determination. The echoes of past revolutions continue to resonate, serving as a powerful warning to those in power and an eternal source of hope for those who dream of a different world.