Beneath the Glimmer: The Unseen Lives of the Barbary Coast Harlots

San Francisco, at the turn of the 20th century, was a city of paradoxes. A burgeoning metropolis rising from the ashes of the Gold Rush, it boasted grand Victorian mansions and cultural aspirations. Yet, beneath this veneer of respectability, a darker, more primal heart beat in its infamous Barbary Coast district. Here, amidst the clamor of saloons, dance halls, and opium dens, thrived a community of women whose lives were inextricably linked to the city’s insatiable appetites: the Barbary Coast harlots. Their stories, often relegated to the shadows or sensationalized into caricatures, offer a stark, humanizing glimpse into the raw realities of survival, exploitation, and, at times, unexpected resilience in a lawless frontier.

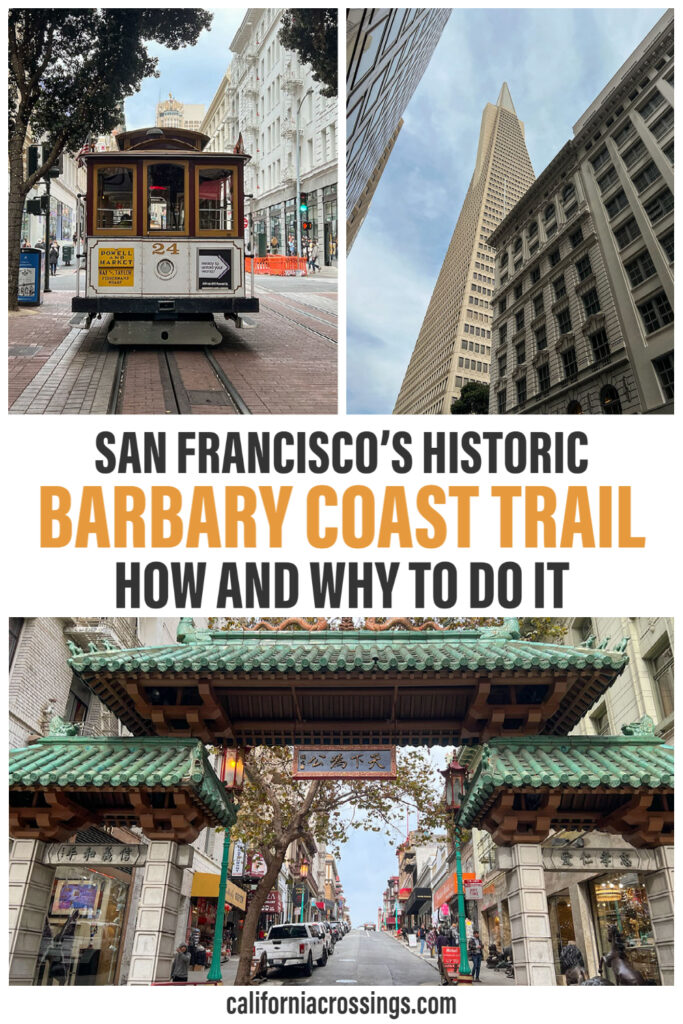

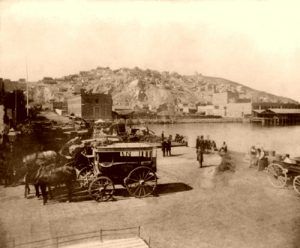

The Barbary Coast, a triangle of streets roughly bordered by Pacific Street, Montgomery Street, and Columbus Avenue, earned its name from the notorious pirate havens of North Africa. It was a place where inhibitions dissolved and vice reigned supreme. Following the Gold Rush of 1849, San Francisco exploded in population, attracting a flood of men—miners, sailors, adventurers, and laborers—eager to strike it rich or simply make a new life. This demographic imbalance, with men outnumbering women by a significant margin, created a fertile ground for the commercial sex industry. The city’s transient nature, coupled with lax law enforcement and a prevailing "anything goes" attitude, allowed the Barbary Coast to flourish as a veritable crucible of pleasure and peril.

For many of the women who found themselves within its notorious confines, the path to becoming a "harlot" was paved with desperation rather than choice. They were a diverse group, hailing from various backgrounds: Irish and German immigrants escaping poverty, young women from rural America seeking opportunity in the bustling city, abandoned wives, and even Chinese women trafficked across the Pacific. Economic necessity was the primary driver. In an era where respectable employment for women was scarce, low-paying, and often exhausting, prostitution offered, for some, the only immediate means of survival. A factory worker might earn a few dollars a week; a prostitute, depending on her standing, could make significantly more, albeit at an immeasurable personal cost.

Historian Herbert Asbury, in his seminal work "The Barbary Coast," vividly describes the district as "a red-light district… more depraved than any other in America." Within this depraved landscape, a distinct hierarchy of prostitution emerged, reflecting the socio-economic strata of both the patrons and the practitioners. At the top were the "parlor houses," elegant establishments often run by formidable madams like the legendary Ah Toy, a Chinese immigrant who defied racial and gender norms to build a powerful enterprise. These houses catered to wealthier clientele, offering luxurious surroundings, fine wines, and women who were often better dressed and educated. The women in parlor houses might enjoy slightly better conditions, including regular meals and a semblance of safety, though they were still beholden to the madam and the whims of their patrons.

Further down the ladder were the "cribs" – small, cramped rooms lining the narrow alleys, often with a simple bed, a washbasin, and a gas lamp. These were the most visible and accessible forms of prostitution, catering to sailors, laborers, and the city’s working poor. The women in cribs endured relentless hours, often beckoning directly from their doorways, exposed to the elements and the constant threat of violence, disease, and exploitation. Their fees were meager, and a significant portion of their earnings went to the "landlord" or pimp who controlled their space. Life in the cribs was a grim existence, marked by rapid physical and emotional deterioration, often leading to addiction as a means of escape.

Beyond the brothels and cribs, prostitution permeated other establishments. "Concert saloons" or "dance halls" employed "B-girls" or "percentage girls" who encouraged patrons to buy overpriced drinks, earning a commission on each sale, with prostitution often an unspoken, yet expected, part of the evening’s entertainment. Sailors, disoriented and flush with pay, were particularly vulnerable to the predatory tactics of these establishments, sometimes waking up on a ship bound for Shanghai, a victim of the notorious "Shanghaiing" gangs that also operated in the district.

The daily lives of these women were a constant tightrope walk between survival and despair. They faced an array of dangers: venereal diseases, unwanted pregnancies, physical assault from patrons or rival pimps, and the ever-present threat of addiction to alcohol or opium, often supplied by their exploiters to maintain control. Medical care was scarce and often inadequate, leading to further suffering and premature death. Few escaped the life; those who did often carried the physical and psychological scars for years.

Societal attitudes towards these women were a complex mix of condemnation and complicity. Victorian morality officially denounced them as "fallen women," ostracizing them from respectable society. Yet, the same society implicitly sanctioned their existence, recognizing their role in siphoning off male desires that might otherwise threaten the "purity" of wives and daughters. Law enforcement, far from being a deterrent, was often deeply corrupt. Police officers frequently accepted bribes, providing protection to brothels and turning a blind eye to illegal activities, further entrenching the power of madams and pimps.

However, the Barbary Coast’s notoriety also sparked outrage and fueled reform movements. Social purity advocates, women’s groups, and religious organizations campaigned tirelessly against prostitution, often focusing on the sensationalized narratives of "white slavery" – the forced abduction and enslavement of innocent young women. While genuine cases of coercion existed, the "white slavery" panic sometimes overshadowed the economic realities that drove many women into the sex trade. These reformers sought to rescue and rehabilitate the "fallen," often establishing missions and shelters, though their efforts were met with mixed success.

One of the most compelling, albeit tragic, aspects of the Barbary Coast harlots’ stories is the scarcity of their own voices. Their experiences were rarely documented from their perspective. They left behind few letters, diaries, or memoirs. Their narratives were largely shaped by male writers, moral crusaders, or law enforcement records, often filtered through the biases of the time. This historical silence makes it challenging to fully grasp their individual dreams, struggles, and moments of defiance or joy. Yet, glimpses emerge from police blotters, court records, and the occasional newspaper report – a woman arrested for defending herself, another testifying against an abusive pimp, a madam asserting her independence in a male-dominated world.

The Barbary Coast era drew to a close with the 1906 earthquake and fire, which devastated much of San Francisco, including parts of the notorious district. While the area quickly rebuilt, the moral climate was shifting. Progressive era reforms gained traction, and the focus on public health and order intensified. In 1917, under pressure from moral crusaders and the federal government (which saw vice districts as a threat to soldiers during World War I), San Francisco officially closed down the Barbary Coast’s red-light district. Brothels were shuttered, and the women were dispersed, often simply moving to other parts of the city or to other burgeoning vice districts across the nation.

Today, the Barbary Coast exists primarily in history books and the occasional tourist brochure, a sanitized version of its former self. But the women who toiled within its confines – the Barbary Coast harlots – remain a poignant reminder of a bygone era. Their lives, though often brutal and short, were not without their complexities. They were victims of circumstance and exploitation, but also, in their own ways, survivors who navigated a treacherous world with varying degrees of agency. Understanding their stories, stripped of sensationalism and moral judgment, allows us to confront the uncomfortable truths about societal inequalities, the enduring demand for commercial sex, and the profound human cost of poverty and limited opportunity. They were more than just "harlots"; they were women who, against immense odds, simply tried to survive in a city that both consumed and discarded them. Their silent echoes continue to resonate, urging us to look beneath the glimmer of history and acknowledge the unseen lives that shaped it.