The Shadow of the Axeman: New Orleans’ Unsolved Symphony of Terror

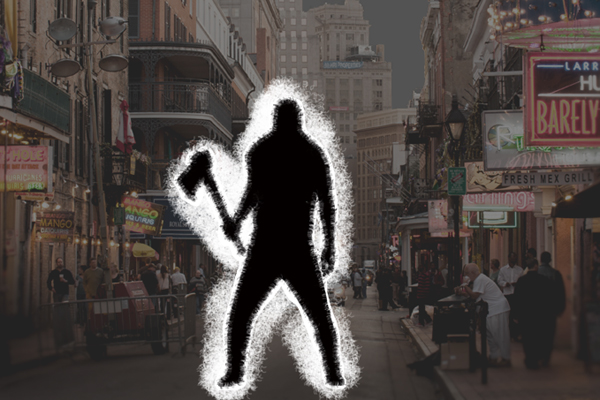

The humid air of New Orleans, usually thick with the languid notes of jazz and the aroma of Creole spices, once hung heavy with a different kind of scent: fear. For a chilling period between 1918 and 1919, the Crescent City found itself gripped by an unprecedented terror, stalked by a phantom killer who wielded an axe and left a trail of bloody mysteries. He was known only as the Axeman, and his reign of terror remains one of America’s most enduring and unsettling unsolved true crime sagas, forever entwined with the city’s dark, jazz-infused folklore.

The Axeman’s shadow fell darkest during a time of global upheaval. World War I had just concluded, and the Spanish Flu pandemic was sweeping the globe, creating an atmosphere of widespread anxiety and loss. Yet, for the residents of New Orleans, a more immediate, localized dread began to take root in the quiet, residential streets, particularly within the close-knit Italian-American community.

The first documented attack occurred on the night of May 23, 1918. Joseph Maggio, a grocer, and his wife Catherine, were found brutally murdered in their bed in their home on Upper Ursulines Avenue. The scene was gruesome: their throats had been cut with a straight razor, and a heavy axe, taken from their own property, was left near their bodies, smeared with blood. Nothing of value appeared to have been stolen, immediately signaling that robbery was not the primary motive. This detail would become a chilling hallmark of the Axeman’s methodology – a silent, almost surgical precision, with the weapon often sourced from the victims’ own sheds or yards.

The city reeled. Police, initially baffled, launched an investigation, but clues were scarce. The Maggio murders were not an isolated incident. Less than a month later, on June 27, Charles, Rosie, and Mary Cortimiglia were attacked in their home in Gretna, across the Mississippi River. Rosie and her two-year-old daughter Mary died, while Charles survived, albeit with severe head injuries. He later claimed to have heard two men arguing outside his home, but his account was inconsistent and unreliable, possibly due to his trauma. Again, an axe was the weapon, and entry was gained by chiseling out a panel from the back door.

The pattern was beginning to emerge: working-class Italian-American families, brutal axe attacks, forced entry through a chiseled door panel, and a perplexing lack of robbery. The fear escalated, and whispers turned into frantic conversations. Was this a single killer? A gang? A vendetta against the Italian community, often stereotyped and marginalized at the time? The police were under immense pressure, yet the killer remained a ghost.

The attacks continued with terrifying regularity. On August 10, 1918, Louis Besumer and his mistress, Harriet Lowe, were attacked in their grocery store apartment. Besumer, though severely injured, survived. Lowe, however, succumbed to her wounds. Besumer, a man with a dubious reputation, briefly became a suspect, but his alibi eventually held, and the true horror of the Axeman’s continued freedom pressed down on the city.

The summer of 1918 ended with New Orleans in a state of siege. Doors were barred, windows secured, and families huddled together, listening to every creak and groan of their old homes. The newspapers, hungry for details and selling rapidly, sensationalized every new development, further fueling the public’s anxiety. The Axeman became a spectral presence, a topic of hushed conversation in every home and establishment.

After a hiatus of several months, the Axeman struck again in March 1919, first targeting Charles and Anna Notto, killing Charles, then Frank Joseph Mancuso and his wife, both surviving the brutal attack. The terror reached a fever pitch, but it was on March 13, 1919, that the Axeman etched himself indelibly into the annals of true crime with an act of chilling audacity that transformed him from a mere murderer into a master manipulator of public fear.

A letter, purportedly from the Axeman himself, was published in the local newspapers. It was a macabre, taunting missive, dripping with menace and an almost supernatural arrogance.

"Hottest Hell, March 13, 1919

Esteemed Mortals:

They have never caught me and they never will. They have never seen me, for I am invisible, even as the ether that surrounds your earth. I am not a human being, but a fiend from hottest hell. I am what you Orleanians and your foolish police call the Axeman.

When I see fit, I shall come and claim other victims. I alone know who they shall be. I shall leave no clue except my bloody axe, besmeared with blood and brains of he whom I have sent below to keep me company.

If you wish, you might tell the police to be careful not to vex me. Of course, I am a just fiend and have no enmity against those who have done me no harm. I merely choose to be the instrument of justice, and I shall punish those whom I see fit.

But, to be exact, at 12:15 (earthly time) on next Tuesday night, I am going to pass over New Orleans. In my infinite mercy, I am going to make a little proposition to you people. Here it is: I am very fond of jazz music, and I swear by all the devils in the nether regions that every person shall be spared in whose home a jazz band is in full swing at the time I have mentioned. If everyone has a jazz band going, well, then, so much the better for you people. One thing is certain and that is that some of your people who do not jazz it on Tuesday night (if there be any) will get the axe.

Well, as I am a fiend from hell, I will now take my leave. Until then, remember that the Axeman is supreme."

This letter, with its diabolical tone and bizarre demand, sent shockwaves through the city. The proposition was simple: play jazz music loudly and continuously that Tuesday night, or face the Axeman’s wrath. The city was faced with an unprecedented dilemma. Was it a hoax? A deranged prankster? Or a genuine threat from a supernatural entity, as the letter suggested?

The response was extraordinary. Jazz, then still a relatively nascent musical form, surged in popularity that night. Every dance hall, saloon, and private home in New Orleans that could afford a band or even a gramophone burst forth with the vibrant, improvisational sounds of jazz. Windows were thrown open, music spilled onto the streets, and a strange, collective defiance filled the night. People who had never listened to jazz before embraced it as a shield. The city danced, not out of joy, but out of a primal instinct for survival.

And just as the Axeman promised, the night passed without incident. No attacks were reported. The eerie quiet that followed the jazz-filled night was almost as unsettling as the fear itself. The Axeman had proven his strange, macabre power over the city.

The reprieve, however, was short-lived. A few months later, in August 1919, Steve Boca was attacked, surviving but unable to identify his assailant. Then, on September 3, 1919, Sarah Laumann was attacked, surviving with severe head injuries. The final known victim was Mike Pepitone, found dead in his bed on October 27, 1919, with his wife, Esther, claiming a man had fled their home just moments before.

Esther Pepitone’s testimony provided a crucial, albeit problematic, lead. She later identified a man named Joseph Mumfre (also known as Manfre) as the killer, claiming he was responsible for her husband’s death and perhaps all the Axeman murders. Mumfre, a known gangster with a violent past, was later shot and killed in Los Angeles in December 1920 by a woman claiming to be Pepitone’s widow, avenging her husband. This act of vigilante justice seemed to offer a grim, albeit unofficial, conclusion to the Axeman saga. However, no definitive proof ever linked Mumfre to the other Axeman attacks, and the timing of his death meant he could not have been responsible for the attack on Sarah Laumann.

The identity of the Axeman remains one of true crime’s most enduring mysteries. Was it a single individual? If so, who? Joseph Mumfre is often cited, but the evidence is circumstantial. Other theories abound: a disgruntled family member of a victim seeking revenge and escalating into a serial killer; a member of the local mafia, using the attacks as a means of control or intimidation; or even a thrill-seeking psychopath, reveling in the terror he unleashed. Some have suggested an anti-Italian sentiment, given the disproportionate number of Italian-American victims, but this doesn’t fully explain the few non-Italian targets.

The Axeman’s story is a chilling reminder of a time when a city was held captive by an unseen force. It speaks to the power of fear, the resilience of a community, and the bizarre ways in which human psychology can manifest. The "jazz or death" letter stands as a unique artifact in criminal history, a testament to the killer’s warped sense of humor and his uncanny ability to manipulate public perception.

Today, the Axeman of New Orleans remains an anonymous legend, a ghostly figure in the city’s rich tapestry of history and folklore. His story has inspired books, songs, and even television series, including a prominent arc in American Horror Story: Coven. Yet, despite the cultural fascination, the fundamental questions persist: Who was he? Why did he kill? And why did he suddenly stop?

The jazz still plays in New Orleans, its vibrant melodies echoing through the old streets. But for those who know the history, there’s a subtle, almost imperceptible undertone to the music, a faint echo of a time when those very notes were a city’s desperate plea for survival, a fragile barrier against the unseen shadow of a killer who wielded an axe and demanded a macabre, melodic tribute. The Axeman’s identity may be lost to time, but his chilling legacy continues to haunt the Crescent City, a silent, unsolved symphony of terror.