The Celestial Charade: How Bat-Men and Unicorns on the Moon Captivated 19th-Century America

In the sweltering New York summer of 1835, a new kind of fever gripped the burgeoning metropolis, one far more potent than any earthly contagion. It was a fever of discovery, of cosmic revelation, sparked by a series of sensational articles published in The New York Sun. What began as a trickle of scientific reporting quickly swelled into a torrent of astounding claims: the Moon, that distant, enigmatic orb, was not merely a barren rock, but a vibrant, living world, teeming with exotic flora, magnificent creatures, and even, most breathtakingly, intelligent, winged humanoids – the "Vespertilio-homo," or bat-men.

This was the Great Moon Hoax, a masterclass in journalistic deception and a testament to the intoxicating power of belief, ambition, and a rapidly expanding public sphere. It was a moment that simultaneously showcased the boundless optimism of an era fascinated by scientific progress and exposed the raw credulity of a public eager for wonders.

The stage for this celestial charade was meticulously set. The early 19th century was a period of immense scientific ferment. Astronomy, in particular, was experiencing a golden age. Sir William Herschel, the discoverer of Uranus, had recently passed, but his son, Sir John Herschel, was carrying on the family legacy, having established a new, powerful observatory at the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa. News of his genuine astronomical endeavors had already reached America, priming the public for further breakthroughs.

It was into this fertile ground of scientific anticipation that The New York Sun, a relatively new and ambitious penny paper, planted its extraordinary seed. Founded just two years prior by Benjamin Day, The Sun aimed to be accessible to the masses, eschewing the partisan political rhetoric of its competitors in favor of sensational local news and human-interest stories. Its motto, "It Shines for ALL," ironically underscored its populist approach, which would soon be exploited for unprecedented gains.

On August 25, 1835, The Sun published the first of six articles, ostensibly reprinted from The Edinburgh Journal of Science. The articles claimed to be accounts from a Dr. Andrew Grant, a supposed colleague of Sir John Herschel, detailing his observations through a revolutionary new telescope. This instrument, described as being of "immense dimensions" and operating on an entirely new principle of "oxy-hydrogen microscope" technology, allowed Herschel to magnify lunar objects to an astonishing degree, making them appear as close as "a hundred yards."

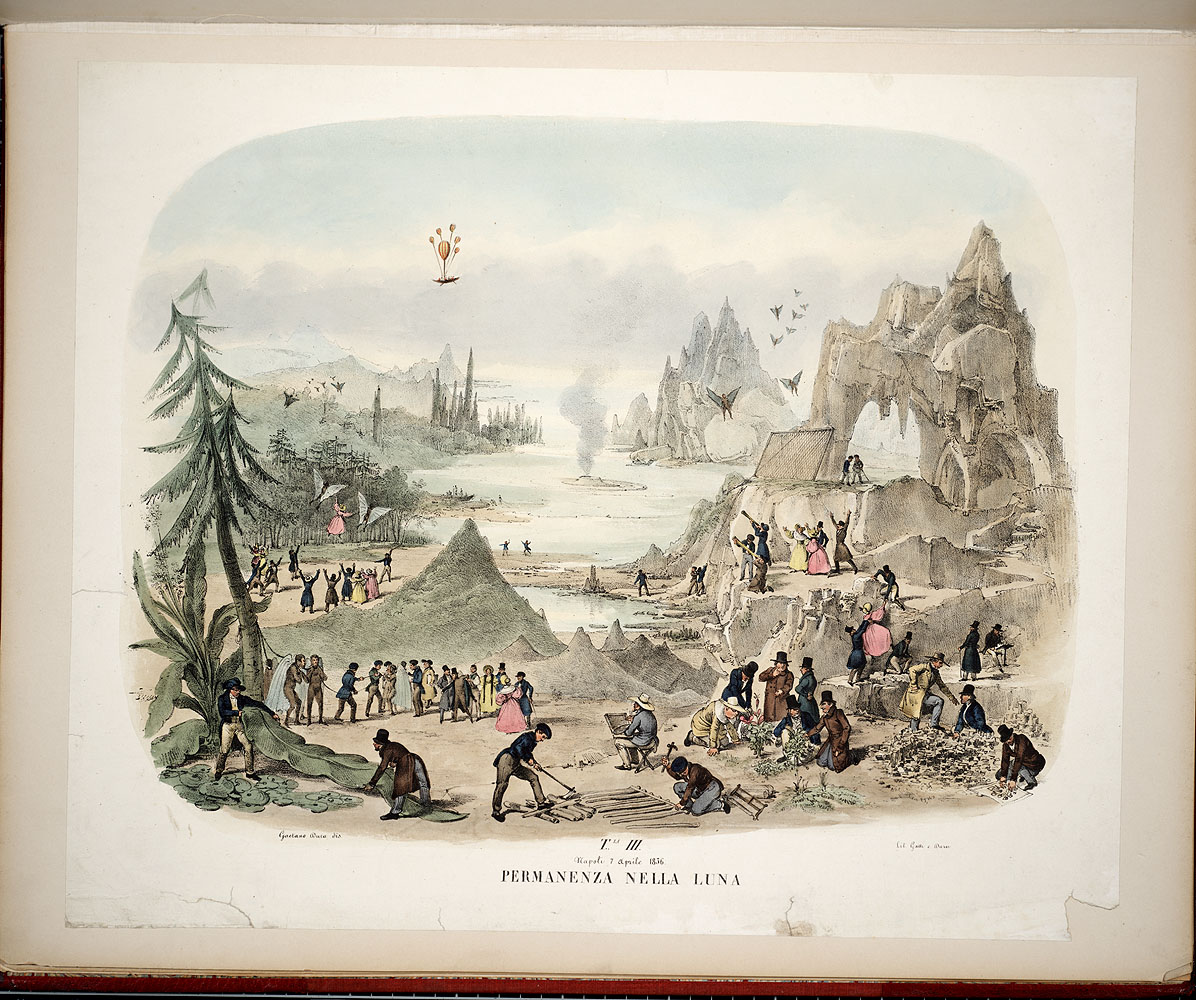

The initial reports were relatively mundane, describing the Moon’s surface with basaltic formations and crimson flowers, building a veneer of scientific plausibility. But quickly, the claims escalated. Dr. Grant, through the Sun‘s reports, began to describe forests, oceans, and rivers. Then came the animals: "a species of bison," a "miniature unicorn," and "two-legged beavers" that constructed their dwellings with fire and walked upright. The descriptions were vivid, meticulously detailed, and delivered with an air of profound scientific authority.

"We counted three score and ten of these animals, in one group," read one article, describing the beavers. "They were about the size of a common goat, and were of a bluish lead colour, and walked erect like human beings."

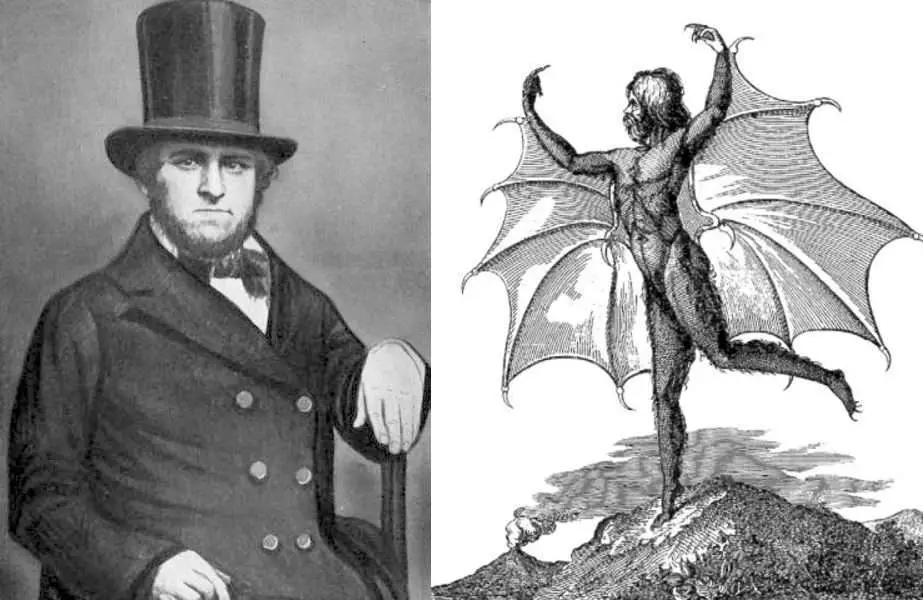

The climax of the hoax arrived with the revelation of the Vespertilio-homo. These were described as graceful, intelligent creatures, "about four feet in height," covered in "a short and glossy copper-coloured hair," and possessing "large wings of a thin, transparent membrane, like that of a bat." They were depicted as living in harmonious societies, engaging in various activities, and even constructing intricate temples, suggesting a level of civilization. One particularly striking passage described them in contemplation: "We saw them distinctly, but for a moment, in one of these temples, which was, if we may so speak, a kind of lunar pantheon."

The public reaction was nothing short of phenomenal. The Sun‘s circulation, already on an upward trajectory, skyrocketed from 8,000 to an unprecedented 19,000 copies a day, making it the highest-selling newspaper in the world at the time. Queues formed outside the Sun office, with people desperate to get their hands on the latest installment of lunar revelations. The articles were reprinted across the country and even internationally. Ministers delivered sermons incorporating the discoveries, scientific societies debated their implications, and even some established scientists were initially swayed, or at least entertained, by the sheer audacity and detail of the reports.

One anecdote, perhaps apocryphal but illustrative of the public mood, tells of Yale students traveling to New York to inspect the original Edinburgh Journal of Science article, only to find it nonexistent. The sheer lack of immediate access to information, combined with the perceived authority of the named astronomers, allowed the deception to flourish.

The author behind this elaborate fabrication was Richard Adams Locke, a talented and witty English journalist working for The Sun. Locke later admitted his intention was partly satirical: to poke fun at the growing trend of sensationalism in the popular press, to lampoon the credulity of the public, and to critique certain philosophical and religious arguments that attempted to reconcile scientific discoveries with biblical interpretations. He reportedly also aimed to outdo other sensational stories of the day, particularly a real pamphlet published by Edgar Allan Poe, "The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall," which involved a balloon journey to the Moon. Poe himself accused Locke of plagiarism, though the two works differed significantly in their approach and execution.

The unraveling of the hoax was gradual. Skepticism had always simmered beneath the surface of public enthusiasm. Rival newspapers, initially caught off guard, began to question the veracity of The Sun‘s claims, particularly when no other scientific journal, let alone Sir John Herschel himself, confirmed the astounding observations. The New York Journal of Commerce, determined to expose the fraud, dispatched a reporter to the Sun office, where a young apprentice eventually confessed that the articles were not from Edinburgh but had been concocted entirely in-house.

Locke, by then a celebrity, publicly acknowledged the deception in mid-September, just weeks after the first article appeared. He claimed his intent was purely to provide "an agreeable amusement to the public," and a "deserved rebuke to the great mass of a credulous community."

The Great Moon Hoax left an indelible mark on American journalism and public consciousness. It cemented The Sun‘s reputation as a purveyor of popular, if sometimes dubious, news, and helped establish the penny press as a powerful force in shaping public opinion. More broadly, it served as a stark reminder of the delicate balance between reporting factual information and pandering to public appetite for the extraordinary.

In an era before instant global communication and widespread scientific literacy, the hoax exposed the vulnerabilities of an information ecosystem ripe for manipulation. It highlighted how a compelling narrative, even one based on elaborate fabrication, could gain traction and be widely believed, especially when cloaked in the guise of scientific authority.

Today, as societies grapple with the pervasive challenges of misinformation, fake news, and alternative facts, the Great Moon Hoax serves as a potent historical precursor. It reminds us that the human desire for wonder, combined with a lack of critical scrutiny, can make us susceptible to even the most outlandish claims. The bat-men of the Moon may have been a charming fiction, but the lessons learned from their brief, spectacular appearance remain as relevant and urgent as ever. The celestial charade of 1835 stands as a timeless cautionary tale, urging perpetual vigilance against the seductive power of deception, whether it promises unicorns on the Moon or something far more mundane, yet equally misleading, closer to home.