The Shifting Sands of Myth: America’s Enduring Legends of Outlaws, Chiefs, and the Wild Frontier

America, a nation forged in revolution and tempered by expansion, is a land perpetually in conversation with its own past. This conversation is rarely a dry recitation of facts; it is a vibrant, often contradictory tapestry woven from history, folklore, and the enduring power of myth. From the gun-slinging outlaws of the Wild West to the stoic chiefs of sovereign nations, the legends of America define its character, reveal its aspirations, and expose its deepest contradictions. They are stories of heroes and villains, of grand visions and tragic injustices, all shaped by the unforgiving landscape and the relentless march of westward expansion.

At the heart of many of these legends lies the frontier – a place where law was often a suggestion, and survival a daily battle. Here, the line between fact and fiction blurred with the speed of a six-shooter. The "OK badmen," as the prompt aptly puts it, became the anti-heroes and dark idols of a burgeoning nation. Figures like Jesse James, the notorious bank and train robber, transcended mere criminality to become a folk hero, a Southern Robin Hood fighting against the perceived injustices of Reconstruction. His legend was meticulously crafted, first by sympathetic newspapers and later by dime novels, portraying him as a chivalrous rebel rather than a ruthless killer. As one contemporary journalist romanticized, "Jesse James was truly a marvel in his chosen profession, a veritable genius of banditry." This romanticized image persists, despite the historical record detailing his gang’s violence and indiscriminate killings. His betrayal and murder by Robert Ford, one of his own gang, only cemented his tragic, legendary status, transforming him from a fugitive into a martyr in the public imagination.

Similarly, Billy the Kid, born Henry McCarty (or William H. Bonney), became synonymous with the untamed spirit of the New Mexico Territory. A youthful, quick-witted outlaw involved in the bloody Lincoln County War, Billy’s legend grew exponentially after his death at the hands of Sheriff Pat Garrett. Stories painted him as a charming, almost innocent figure forced into violence, capable of daring escapes and possessing an uncanny resilience. While he was undeniably a killer, the popular narrative often overlooked the brutal realities of his actions, preferring instead to focus on his youth and his defiance of authority. His story, like James’s, was amplified by sensationalized accounts, ensuring his immortality as a symbol of the American frontier’s lawless allure.

Yet, for every "badman," there were lawmen and figures of order who also achieved legendary status, often with their own shades of grey. Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday, central to the infamous Gunfight at the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Arizona, embody this duality. Earp, a gambler and lawman, and Holliday, a dentist turned professional gambler and gunfighter, became legendary figures whose actions were fiercely debated even in their own time. Was the O.K. Corral a legitimate law enforcement action, or a pre-meditated murder? The truth, as with most legends, lies somewhere in the middle, continuously reinterpreted through countless books, films, and television series. Their stories speak to a fundamental American fascination with justice meted out at the barrel of a gun, and the complex moral calculus of survival in a harsh land. As the adage, often attributed to the film The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, goes: "When the legend becomes fact, print the legend." This sentiment perfectly encapsulates how America has often chosen its myths over its mundane truths.

In stark contrast, and often in direct conflict, with these legends of outlaws and lawmen are the profound and ancient legends of the Indian nations. Long before European settlers arrived, the continent was home to hundreds of distinct peoples, each with rich oral traditions, creation myths, trickster tales, and historical narratives that defined their understanding of the world and their place within it. These legends are not merely stories; they are foundational pillars of culture, spirituality, and identity, deeply rooted in the land itself.

For the Lakota, for instance, the Black Hills (Paha Sapa) are not just mountains but a sacred center of the world, where their people emerged. Their legends speak of powerful spirits, of the White Buffalo Calf Woman who brought them the sacred pipe and their ceremonies, and of courageous warriors who defended their way of life. Figures like Sitting Bull (Tatanka Iyotake), the Hunkpapa Lakota leader and holy man, and Crazy Horse (Tȟašúŋke Witkó), the Oglala Lakota warrior, are not merely historical figures but legendary symbols of resistance, spiritual strength, and unwavering dedication to their people’s sovereignty. Sitting Bull’s prophetic visions and Crazy Horse’s unmatched bravery in battle, particularly at the Battle of Little Bighorn (Greasy Grass), solidified their place in both Native American and broader American legend. Their stories underscore a profound connection to the land and a fierce determination to protect it, even in the face of overwhelming odds. "Let us put our minds together and see what life we can make for our children," Sitting Bull famously urged, a sentiment that echoes through generations of Indigenous resilience.

Further to the Southwest, the Apache people’s legends are steeped in their nomadic, warrior culture, their deep knowledge of the desert, and their fierce independence. Geronimo (Goyaałé), an Apache leader and medicine man, became a legendary figure of resistance against both Mexican and American expansion. His repeated escapes from capture and his ability to lead small bands of warriors in guerrilla warfare against much larger forces made him a symbol of defiance. Though ultimately captured, his legend as an indomitable fighter and spiritual leader endures, reflecting the Apache’s deep reverence for freedom and their ancestral lands. His famous words, "I was warmed by the red fire of the sun, and the red fire of the Apache blood," encapsulate the spirit of his enduring struggle.

The legends of Native American nations also include a rich pantheon of spiritual figures and tricksters. Coyote, for example, is a ubiquitous figure in the myths of many Plains and Southwestern tribes, a mischievous creator and destroyer who teaches through his follies, bringing both wisdom and chaos. Raven, in the Pacific Northwest, is another powerful trickster, often responsible for bringing light to the world or shaping the landscape through his cunning. These stories, passed down through generations via oral tradition, are not merely entertainment; they are moral compasses, historical records, and guides to understanding the natural world. They reveal a worldview vastly different from that of the European settlers, one built on reciprocity with nature, communal responsibility, and a cyclical understanding of time.

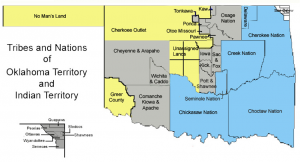

The collision of these two legendary worlds – the expanding American frontier with its "badmen" and lawmen, and the ancient, deeply rooted cultures of the Indian nations – created a new layer of mythmaking. Manifest Destiny, the belief in America’s divinely ordained right to expand across the continent, became a powerful narrative, framing the displacement of Native peoples as an inevitable, even righteous, progression. In this narrative, Native Americans were often cast as either "noble savages" or bloodthirsty obstacles to progress, denying their complex humanity and sovereign nationhood. The forced removal of tribes, epitomized by the Trail of Tears (the forced relocation of Cherokee and other Southeastern Indigenous peoples), became a tragic legend of national shame for some, while for others, it was a necessary evil for expansion.

Yet, within this clash, new legends emerged. The Ghost Dance movement, a spiritual revival among Plains tribes in the late 19th century, was a powerful, if tragically misunderstood, attempt to reclaim spiritual sovereignty and restore a lost way of life. The subsequent Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890, where hundreds of unarmed Lakota men, women, and children were killed by the U.S. Army, stands as a horrific testament to the violence of the frontier, but also as a profound legend of endurance and the unyielding spirit of a people. For Native Americans, Wounded Knee is not just history; it is a wound, a warning, and a symbol of their ongoing fight for justice and recognition.

Beyond the immediate conflict, other legends helped shape the American psyche, often blurring the lines between human and superhuman. Figures like Davy Crockett, the "King of the Wild Frontier," and Daniel Boone, the archetypal frontiersman, became legendary for their wilderness skills, courage, and their role in "taming" the wilderness. Crockett’s heroic, though perhaps embellished, stand at the Alamo cemented his image as an indomitable patriot. Similarly, folklore figures like the gigantic lumberjack Paul Bunyan and his blue ox, Babe, or the cowboy of impossible feats, Pecos Bill, embody the nation’s ambition, its desire to conquer nature, and its fascination with outsized heroes who could wrestle mountains into submission. These tall tales, though clearly fantastical, served to reinforce an identity of strength, ingenuity, and a pioneering spirit essential to a young nation’s self-perception.

In conclusion, the legends of America are not static relics of the past; they are living narratives, constantly reinterpreted and debated. The "OK badmen" and their adversaries, the powerful chiefs and spiritual leaders of the Indian nations, and the broader cast of frontier heroes all contribute to a complex mythology that reflects America’s journey from a collection of colonies to a global power. They speak to the nation’s love of individualism, its sometimes brutal expansion, its deep spiritual roots, and its enduring struggle to reconcile its ideals with its realities. These legends remind us that history is not just what happened, but also how we remember it, and how those memories continue to shape who we are as a people, forever oscillating between the romanticized myth and the uncomfortable truth. The shifting sands of these myths continue to define America, inviting constant re-examination and ensuring that the stories of its past remain as vibrant and contested as its present.