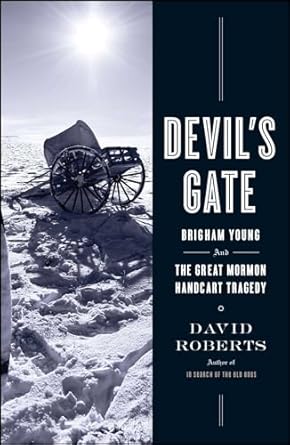

The Unfolding Saga: How the Mormon Handcart Tragedy Became an Enduring American Legend

America is a land woven with legends, tales that transcend mere history to become foundational narratives of courage, sacrifice, and the relentless pursuit of an ideal. From the rugged individualism of the frontier to the collective triumphs of nation-building, these stories illuminate the very soul of a continent. Among these, few resonate with such stark power and profound human drama as the Mormon Handcart Tragedy of 1856 – a saga not of grand battles or political intrigue, but of ordinary people pushed to extraordinary limits, whose faith and resilience etched an indelible mark on the American spirit.

It is a story that begins with a dream, a vision of a new Zion in the desert promised land of Utah. By the mid-19th century, members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (often called Mormons) faced relentless persecution in the eastern United States, driving them to seek refuge in the remote Great Salt Lake Valley. Under the prophetic leadership of Brigham Young, thousands made the arduous trek westward, most by wagon train. But for the poorest converts, primarily from Great Britain and Scandinavia, even a wagon was an unaffordable luxury.

The Bold Experiment: Handcarts and Hope

In 1856, Brigham Young proposed a radical, cost-saving alternative: handcarts. These two-wheeled carts, designed to be pulled by hand, could carry a family’s meager possessions – about 17 pounds per person, including food and clothing. The plan promised a faster, cheaper journey, allowing thousands more to "gather to Zion." It was a bold experiment, born of necessity and fervent faith. "The Saints will get to Zion quicker," Young declared, "by pulling handcarts than by any other means."

Optimism abounded. Thousands eagerly embraced the plan, seeing it as a direct path to their promised land. Five handcart companies were organized that year, but it was the fourth and fifth – the Willie Handcart Company and the Martin Handcart Company – that would become synonymous with unimaginable suffering and heroism. These companies, composed largely of recent European converts, departed Iowa City dangerously late in the season, due to delays in equipment fabrication and a misunderstanding of the vast distances involved.

As summer waned and the autumn winds began to bite, a sense of foreboding settled over the plains. The 1,500-mile journey from Iowa to Utah was daunting even in ideal conditions; attempting it with handcarts, in late fall, was a gamble against nature’s most unforgiving forces.

The Descent into Tragedy: Winter’s Cruel Embrace

The first three companies arrived in Salt Lake City with relatively few casualties, bolstering the initial confidence in the handcart plan. But for the Willie and Martin companies, destiny had a colder, crueler hand to play. They pushed onward through what is now Nebraska and Wyoming, battling not just the relentless miles but also dwindling provisions and the encroaching specter of winter.

The weather turned with brutal swiftness. Early blizzards, unprecedented for October, swept across the plains, burying the nascent trails under feet of snow. The thin clothing of the pioneers, accustomed to milder European climates, offered little protection against the howling winds and plummeting temperatures. Food rations dwindled to meager portions, then to near starvation. Buffalo chips were burned for warmth, and raw hides gnawed on for sustenance.

The handcarts themselves, poorly constructed and overloaded, began to break down. Axles snapped, wheels crumbled, and the pioneers, already weakened by hunger and fatigue, were forced to repair them in freezing conditions or abandon their precious possessions. Death became a constant companion. Frostbite claimed fingers and toes, gangrene set in, and hypothermia silently stole lives, especially among the elderly and the very young.

A survivor from the Martin Company, John Chislett, recounted the harrowing conditions: "Many began to freeze to death… The sight of our camping ground was dreadful to behold. All around us lay the dead and dying. The wails and groans of the sufferers were heart-rending." The ground, too hard to dig graves in, often meant shallow burials, or worse, leaving bodies exposed to the elements.

A Testament of Faith Amidst Despair

Yet, amidst this profound suffering, an astonishing resilience emerged. The pioneers sang hymns, prayed together, and offered what little comfort they could to one another. Their faith, far from being extinguished by the ordeal, often deepened. Francis Webster, a member of the Martin Company, famously declared years later when asked if he ever regretted the journey: "I have pulled my handcart when I was so weak that I could hardly put one foot ahead of the other. I have had to help pull my cart when I was sick and my hands were so sore that I could scarcely touch anything. But I never once murmured or complained. …Every one of us who survived that winter of 1856 will remember the Handcart Company for our faith, our devotion, and the love of God."

The pioneers’ suffering was compounded by the fact that they were isolated, hundreds of miles from the nearest settlement, with no one aware of their desperate plight until it was almost too late.

Brigham Young’s Call to Rescue

News of the unfolding disaster finally reached Salt Lake City in early October through a few advance riders who had managed to push ahead. Brigham Young, learning of the dire circumstances of the Willie and Martin companies, was galvanized into action. On October 4, 1856, he addressed a general conference, his voice reportedly filled with emotion:

"I will tell you what your faith, religion, and duty are, at the present moment. These are the people who are now on the plains, and what we want of you is to go and bring them in… I will not ask you to go, but I will command you to go… and bring in those people now on the plains."

His words ignited an immediate and fervent response. Within hours, wagons were loaded with food, blankets, and supplies. Men volunteered, leaving their own families and farms, knowing they would face the same brutal winter conditions. It was an unprecedented rescue effort, a testament to the strong communal bonds and unwavering compassion that characterized the early Mormon settlement.

The Race Against Death: Rescuers to the Rescue

The rescue parties, led by seasoned frontiersmen, rode out into the unforgiving wilderness, racing against time and the elements. They battled the same blizzards and bone-chilling cold that were decimating the handcart companies. The first rescuers reached the Willie Company near what is now known as Rock Creek, Wyoming, on October 21. The scene they encountered was horrific: emaciated figures, many with frozen limbs, huddled together, some too weak to even acknowledge their saviors.

A rescuer, C.R. Savage, described the scene: "When we reached them, many were lying in the snow, too weak to move. Others were just sitting there, staring into space with vacant eyes. The living were almost as numerous as the dead." The arrival of the rescue wagons, laden with food and warmth, was literally a lifeline, though for many, it came too late.

The Martin Company, further behind and having endured even longer without relief, was found several days later, in a place now known as Martin’s Cove. Their suffering had been even more prolonged, and the death toll higher. Survivors spoke of the sheer joy and overwhelming relief upon seeing the rescue party, even as they continued to bury their dead.

The Cost and the Legacy

The journey back to Salt Lake City was still fraught with peril. Many died even after being rescued, succumbing to the lingering effects of starvation and exposure. Estimates vary, but it is believed that around 200 members of the Willie Company and 150-200 from the Martin Company perished, along with others from the earlier companies, bringing the total death toll of the 1856 handcart pioneers to over 600. It remains one of the worst disasters in the history of westward migration in America.

The Handcart Tragedy left an indelible scar on the collective memory of the Latter-day Saints. It became a foundational narrative, a powerful symbol of their faith, sacrifice, and the strength of their community. It taught invaluable lessons about preparation, leadership, and the limits of human endurance, even when fueled by spiritual conviction.

Today, the story of the handcart pioneers is retold through books, films, and historical reenactments. Martin’s Cove and other sites along the trail have become sacred ground, drawing thousands of visitors who seek to walk in the footsteps of those who suffered and survived. Descendants of the pioneers often speak of their ancestors’ ordeal with a mixture of reverence and awe, a powerful connection to a past that shaped their identity.

Beyond its significance to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Mormon Handcart Tragedy is an enduring American legend. It is a story that speaks to universal themes: the human capacity for hope in the face of despair, the indomitable will to survive, the power of collective compassion, and the profound cost of chasing a dream. It reminds us that American legends are not just about conquest and discovery, but also about the quiet, desperate heroism of those who, with little more than faith and a handcart, dared to forge a new life in a vast and unforgiving land. Their story, etched in snow and ice, continues to inspire, a testament to the enduring power of the human spirit.