>

The Arduous Path to Destiny: Legends Forged on the Oregon-California Trail

The American spirit, often romanticized in folklore and film, finds its most visceral expression not in grand battles or political manifestos, but in the relentless, dust-choked journey across the continent. At the heart of this national mythos lies the Oregon-California Trail, a 2,000-mile ribbon of ambition, despair, and unwavering hope that etched itself into the very fabric of the nation. It was more than a mere path; it was a crucible where the legends of America were forged, a testament to human endurance against the vast, untamed wilderness. This journalistic exploration delves into the timeline of this iconic trail, revealing the stories, the sacrifices, and the indelible marks left by those who dared to "Go West."

The Genesis of a Dream: Pre-1840s and the Call of the West

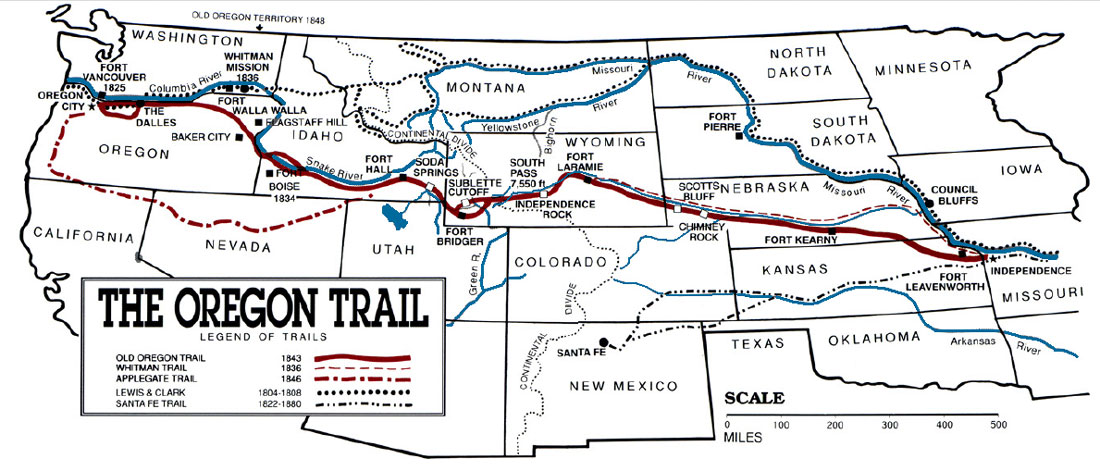

Before the great migrations, the idea of the American West was a blend of myth and sparse reality. Lewis and Clark’s expedition (1804-1806) had charted the northern reaches, but the interior remained largely the domain of fur trappers and mountain men – solitary figures like Jedediah Smith and Jim Bridger, whose tales of fertile valleys and abundant resources slowly trickled back East. These early explorers, often unsung, laid the groundwork, identifying the passes and water sources that would later become critical waypoints.

The early 19th century was a period of burgeoning national identity, fueled by the concept of "Manifest Destiny"—a divinely ordained right, articulated by journalist John O’Sullivan in 1845, for the United States to expand its dominion across the continent. This ideological fervor, coupled with economic depressions in the East (like the Panic of 1837) and the promise of free, fertile land in Oregon or instant wealth in California, created an irresistible pull. The West was not just a destination; it was a second chance, a blank canvas for a new life.

The First Trickle: 1841-1842 – Pioneers and the Perilous Unknown

The earliest attempts to traverse the full length of what would become the Oregon Trail were tentative and fraught with peril. In 1841, the Bidwell-Bartleson Party, comprising about 69 people, became the first group to attempt to cross the continent in wagons. Their journey was a harrowing lesson in the realities of the West; they abandoned their wagons in Nevada and continued on foot, many eventually making it to California. Their struggles underscored the immense challenges and the sheer audacity of the undertaking.

By 1842, more organized efforts began. Elijah White led a small group, including missionaries and their families, to Oregon. While not a massive influx, these early pioneers proved that the journey, though arduous, was survivable. They followed the Platte River, crossed the Continental Divide at South Pass (a crucial, relatively easy crossing discovered by fur trappers), and navigated the treacherous Snake River Plain. Each mile carved out by these initial expeditions was a step towards demystifying the unknown and solidifying the route for those who would follow.

The Great Migration: 1843-1845 – The Trail Takes Shape

The year 1843 marked a turning point. Led by Marcus Whitman, a missionary who had previously traveled the route, approximately 1,000 people and 120 wagons set out from Independence, Missouri, in what became known as "The Great Migration." This was no longer a small band of adventurers; it was a community on the move, carrying with them the infrastructure of a nascent society. The sheer scale of this migration demonstrated the viability of the trail for large-scale settlement.

"We felt as if we were leaving the world behind," wrote Lavinia Porter, a pioneer of the era, capturing the profound sense of departure and the unknown that awaited them.

These years saw the trail solidify. Key landmarks like Fort Laramie (a fur trading post turned military fort) became crucial resupply points and safe havens. The typical journey, lasting four to six months, began to develop a rhythm: spring departure to avoid winter snows, crossing the arid plains in summer, and reaching the fertile valleys before the autumn rains. However, even with increasing numbers, the trail remained a gauntlet of challenges: cholera and other diseases claimed countless lives, accidents were common, and the sheer monotony and physical exertion tested the limits of human endurance. It is estimated that one in ten pioneers died on the trail, leaving behind a solemn string of graves marking their westward progress.

The Fork in the Road: 1846-1848 – California’s Gold Beckons

While Oregon remained the primary destination for many seeking agricultural land, 1846 brought a fateful diversion. As traffic increased, so did the desire for shortcuts. The infamous Donner Party, seeking to save time, opted for "Hasting’s Cutoff" through the Great Salt Lake Desert. This ill-fated decision, combined with early heavy snowfall in the Sierra Nevada mountains, led to one of the most tragic and legendary episodes in American history. Of the 87 members, 42 perished, many resorting to cannibalism to survive. The Donner Party became a stark, chilling legend—a cautionary tale etched into the collective memory of westward expansion, reminding all of the unforgiving nature of the wilderness.

Then, in January 1848, a discovery at Sutter’s Mill in California fundamentally altered the trajectory of the trails. James W. Marshall’s discovery of gold ignited a frenzy that would reshape the West. The sleepy Mexican territory of Alta California, recently acquired by the U.S. after the Mexican-American War, was suddenly the epicenter of global attention.

The Gold Rush Deluge: 1849-1850s – California’s Heyday

1849 marked the peak of the California Trail. The "Forty-Niners," a diverse horde of hopefuls from across America and the world, swelled the ranks of those heading West. The trail, once a path for families seeking new homes, transformed into a thoroughfare for fortune-seekers. An estimated 300,000 people migrated to California between 1848 and 1855.

"The plains are literally covered with wagons," wrote one observer in 1849, describing the unprecedented congestion.

The trails became more defined, with ruts several feet deep in places, still visible today. Trading posts and ferries sprang up, eager to profit from the endless stream of migrants. However, this massive influx also brought increased tensions with Native American tribes, whose lands and resources were increasingly encroached upon. The romanticized image of peaceful pioneering often overshadowed the violent conflicts that became an unfortunate reality of westward expansion. Disease, particularly cholera, continued to be a relentless killer, often sweeping through entire wagon trains.

Throughout the 1850s, both the Oregon and California Trails continued to see heavy traffic, though the motivations diversified. While gold still lured many to California, Oregon continued to attract farmers and those seeking a more settled life. New routes, such as the Mormon Trail (leading to Salt Lake City, established in 1847), also diverted some traffic. The trail was dynamic, adapting to the changing needs and desires of the American populace.

The Twilight of the Wagons: 1860s and the Iron Horse

By the 1860s, the era of the great wagon trains began to wane. The Pony Express (1860-1861) offered a fleeting, romantic interlude of rapid communication, but it was a temporary solution. The true harbinger of change was the railroad.

The American Civil War (1861-1865) briefly slowed westward migration, but the federal government’s commitment to a transcontinental railroad remained. On May 10, 1869, at Promontory Summit, Utah, the "Golden Spike" was driven, connecting the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads. This momentous event, hailed as a triumph of engineering and national unity, signaled the definitive end of the Oregon-California Trail’s dominance. The arduous, months-long journey by wagon was rendered obsolete by a trip that now took days, not months, in relative comfort and safety.

The Enduring Legacy: Legends Etched in Landscape and Spirit

The wagons stopped rolling, the dusty ruts slowly faded, and the campsites grew quiet. Yet, the Oregon-California Trail remains one of America’s most potent legends. It wasn’t just a path to new land; it was a crucible that forged fundamental American characteristics: resilience, self-reliance, optimism, and an unyielding belief in the future.

The hundreds of thousands who traversed those 2,000 miles left an indelible mark on the nation. They settled states, built communities, and laid the economic and social foundations of the American West. Their stories, of triumph over adversity, of heartbreak and loss, of unwavering courage, continue to resonate. From the Donner Party’s tragic lesson to the Gold Rush’s intoxicating promise, each anecdote contributes to a collective memory of a nation continually reinventing itself.

Today, portions of the trail are preserved as national historic sites, allowing visitors to walk in the footsteps of those pioneers. The ruts are still visible, a testament to the immense human effort that transformed a wilderness into a nation. The Oregon-California Trail is more than a historical artifact; it is a living legend, a powerful reminder of the raw human spirit that shaped the destiny of a continent and, in doing so, created the enduring legends of America. It is a story not just of westward expansion, but of the relentless human drive to seek a better life, no matter the cost.