Beyond the Gallop: Unearthing the Pony Express’s "Division Two"

The very name "Pony Express" conjures a vivid tableau in the American imagination: a lone rider, silhouetted against a vast, untamed landscape, a blur of horse and man, carrying the hopes and news of a burgeoning nation. It is a legend etched deep into the bedrock of American identity, synonymous with speed, courage, and the relentless march of progress across a formidable frontier. Yet, like many grand narratives, the popular image often focuses on the spectacular, the "Division One" of heroic riders and record-breaking dashes. What often remains in the shadows, the unsung "Division Two" of this epic, is the gritty, often brutal reality that made the impossible possible: the desolate stations, the tireless stock tenders, the unyielding terrain, and the sheer, arduous logistical ballet that underpinned every thundering hoofbeat.

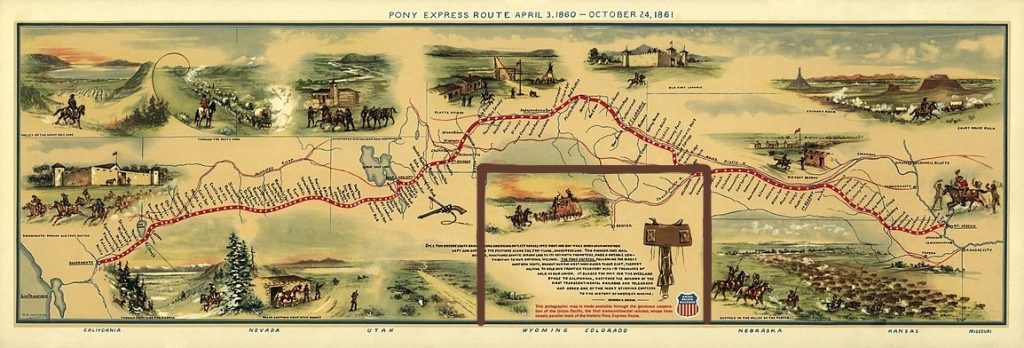

For 18 short, incandescent months between April 1860 and October 1861, the Pony Express was America’s lifeline. Before the transcontinental telegraph could stitch the continent together, before the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads would meet at Promontory Summit, the Pony Express bridged the 1,900 miles between St. Joseph, Missouri, and Sacramento, California. Its mission was simple yet audacious: deliver mail across the vast American West in just ten days, a feat that previously took weeks or even months. This was more than just a mail service; it was a desperate gamble to bind a nation teetering on the brink of civil war, to keep California firmly within the Union’s orbit, and to assert American ingenuity against the wildest odds.

The iconic image – the young, daring rider clinging to his saddle as his mount devours the miles – is the celebrated "Division One" of the Pony Express. These were the rock stars of the frontier, immortalized in dime novels and later in Hollywood. Names like William "Buffalo Bill" Cody, though his service was brief and largely embellished, became synonymous with the legend. The sheer audacity of the concept – a relay of some 500 horses, 190 way stations, and 80 riders operating in shifts – was revolutionary. Mark Twain, observing the Pony Express in his 1872 memoir Roughing It, perfectly captured its allure: "The rider’s mail-bag had not six letters in it… but it was the most spirited and fascinating thing that any age has produced."

But to truly understand the legend, we must delve into its "Division Two." This isn’t a formal designation, of course, but a metaphor for the often-overlooked components that were just as vital, if not more so, than the celebrated riders themselves. "Division Two" encompasses the brutal geography, the isolated support staff, the relentless dangers that lurked in every shadow, and the sheer logistical grind that made the entire operation function. It’s the story behind the speed, the grit beneath the glory.

Consider first the geography. While the eastern leg of the route, from St. Joseph through Kansas and Nebraska, presented its own challenges with prairie storms and occasional skirmishes, it was the western half – the "Division Two" heartland – that truly tested the limits of human endurance. From the forbidding alkali deserts of Nevada to the dizzying heights of the Sierra Nevada mountains, and through the territories of often-hostile Native American tribes, this was a land designed to break men and beasts. Riders in this division faced not just the elements – searing summer heat, blizzards that buried trails under feet of snow, and flash floods – but also the stark, soul-crushing isolation.

The stations themselves, often little more than crude dugouts or log cabins, were the critical nodes of this system, and their keepers were the unsung heroes of "Division Two." These men, often ex-soldiers or hardened frontiersmen, lived lives of profound loneliness and constant peril. Their duties were endless: tending to the weary horses, feeding and sheltering the riders, guarding the precious mail, and, perhaps most critically, simply surviving. A typical station might house two or three men, miles from the nearest settlement, armed against bandits and Native American raids. Their stories are rarely told, but without their unwavering commitment, the relay would have broken down. They were the ground crew, the pit stop mechanics, the lifeline in the wilderness.

The Paiute War of 1860, for instance, erupted just weeks after the Pony Express began operations, directly impacting its western routes. Over 150 horses were stolen, numerous stations were burned to the ground, and several station keepers and riders lost their lives. This wasn’t just a minor disruption; it was an existential threat to the entire enterprise. The bravery of the riders who continued to run the gauntlet, and the resilience of the station keepers who rebuilt and stood their ground, truly cemented the legend. This was "Division Two" at its most visceral – the fight for survival on a daily basis.

Beyond the station keepers were the stock tenders, the wranglers, the blacksmiths, and the cooks – an entire ecosystem of support staff, all vital to the operation. The quality of the horses was paramount; they were bred for speed and stamina, and their care was meticulous. Each horse would run approximately 10-15 miles before being replaced by a fresh mount at a relay station. This required a constant supply of fit horses, expertly trained and ready to sprint at a moment’s notice. The logistics of feeding and watering these animals in such remote locations, especially during harsh winters, was a monumental undertaking, demanding foresight, resourcefulness, and sheer muscle.

The riders themselves, while celebrated, also experienced the "Division Two" reality. They were typically young, often teenagers, chosen for their small stature (to minimize weight) and their fearlessness. The famous advertisement, possibly apocryphal but illustrative of the spirit, read: "Wanted: Young, skinny, wiry fellows not over eighteen. Must be expert riders, willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred. Wages $25 a week." While the "orphans preferred" part is likely hyperbole, it speaks to the expendability and isolation of these daring youths. Their pay, at the time, was excellent, a testament to the risks involved. They carried not just mail, but often a revolver, a knife, and their own profound sense of loneliness. Every journey was a test of endurance, every shadow a potential threat.

The psychological toll of such a life is hard to overstate. Imagine riding for hours, sometimes through the dead of night, knowing that any broken leg, any lost horse, any unexpected ambush could spell disaster, or worse, death. The riders were constantly on edge, relying on their wits, their horsemanship, and a healthy dose of luck. Their commitment was not just to the mail, but to the idea it represented: connection, progress, and the unwavering will of a young nation.

The Pony Express, in essence, was a triumph of management and logistical planning as much as it was a testament to individual bravery. The firm of Russell, Majors, and Waddell, already experienced in overland freighting, poured vast sums into the enterprise, often operating at a significant loss. Their gamble was not just on delivering mail, but on securing lucrative government contracts for future transcontinental communication. It was a business venture wrapped in an adventure, driven by the pressing political needs of the era. President Lincoln’s inaugural address in March 1861, for instance, was carried by Pony Express to California, demonstrating the critical role it played in national cohesion during a tumultuous period.

When the telegraph wire finally connected East and West in October 1861, the Pony Express became instantly obsolete. Its demise was swift and unceremonious, a testament to the relentless march of technological progress. Yet, its brief existence burned a permanent brand into the American psyche. It became more than a mail service; it became a symbol of American grit, ingenuity, and the pioneering spirit.

In retrospect, the legend of the Pony Express is not merely about the speed of its "Division One" riders, but about the collective effort of its "Division Two" – the countless, nameless individuals who toiled in the shadows, battling nature, isolation, and danger to keep the chain unbroken. It is the story of the desolate station keeper, scanning the horizon for a speck of dust that might signify either hope or peril. It is the tale of the stock tender, ensuring the next horse was fresh and ready. It is the testament to the resilience of a system, built on sheer will and determination, that defied the odds.

The Pony Express, therefore, stands as a multifaceted legend. Its "Division One" captures our imagination with its heroic dash across the plains, but its "Division Two" reminds us of the profound human cost, the logistical genius, and the unyielding spirit of those who, in their own way, rode alongside the famous couriers, shaping the very fabric of the American West. It’s a legend that reminds us that behind every grand achievement, there’s an intricate, often challenging, and equally vital story of the unsung heroes who made it possible.