Okay, here is a 1200-word article in English about the legends of America, focusing on the Pony Express Division Three, written in a journalistic style.

The Ghost Riders of the Great Basin: Unearthing the Legend of Pony Express Division Three

In the grand tapestry of American legends, where towering figures like Paul Bunyan and the daring exploits of the Wild West gunfighters cast long shadows, few sagas capture the raw, unyielding spirit of a nation forging its destiny quite like the Pony Express. A brief, audacious flicker of speed and courage across a continent, its story is etched into the very bedrock of American identity. Yet, within this iconic narrative, lies a segment particularly steeped in peril and forgotten heroism: Division Three. This stretch, snaking through the desolate, unforgiving landscapes of what is now Nevada and Utah, was not merely a route; it was a crucible, forging legends out of young men and their swift steeds against the backdrop of an untamed wilderness and escalating conflict.

The year is 1860. The United States is a nation teetering on the brink, its eastern and western halves separated by an immense, often hostile, expanse. California, booming with gold and population, felt a world away from Washington D.C., where the drums of civil war were beginning to beat. Urgent communication was not just a convenience; it was a strategic imperative. Enter the Pony Express: an audacious, privately-funded venture promising to deliver mail from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Sacramento, California, in a blistering ten days – a feat considered impossible by many.

The call went out, echoing the rugged individualism of the age: "Wanted: Young, skinny, wiry fellows, not over eighteen. Must be expert riders, willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred. Wages $25 a week." These were the riders, barely men, who would become the sinews of a new kind of communication network. Their uniform was minimal, their equipment sparse: a leather mochila (a saddle cover with four locked mail pockets), a lightweight saddle, and a trusted horse. Speed was paramount; every ounce mattered.

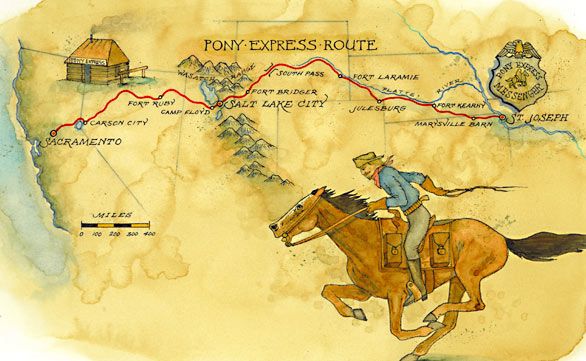

The nearly 1,900-mile route was divided into five divisions, each overseen by a superintendent. While all divisions presented their own unique challenges – the humid plains of Missouri, the treacherous Rockies, the final dash through California’s Sierra Nevada – it was Division Three that truly tested the limits of human endurance and horseflesh.

The Gauntlet of the Great Basin

Division Three, roughly stretching from Ruby Valley, Nevada, to Salt Lake City, Utah, encompassed some of the most barren and dangerous terrain imaginable. Here, the Great Basin unfurled itself: a vast, arid expanse of shimmering salt flats, jagged mountain ranges, and sparse, sagebrush-dotted valleys. Water was a precious commodity, often miles apart. The climate was extreme, swinging from scorching summer temperatures that could cook a man alive to brutal winter blizzards that buried trails under feet of snow.

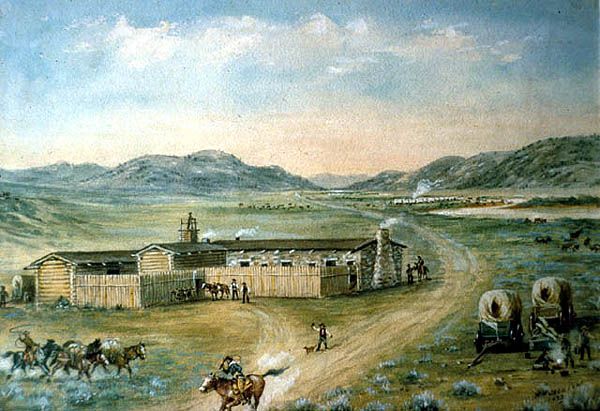

For the Pony Express rider, this division was a relentless gauntlet. Unlike the more populated sections, there were few towns or settlements to offer respite. Station stops, typically ten to fifteen miles apart, were often isolated shacks, manned by equally isolated station keepers and stock tenders, their only company the wind and the constant threat of the unknown. These men, too, were integral to the legend, holding lonely outposts of civilization in the heart of the wilderness, readying fresh horses for the next breathless rider.

Mark Twain, who would later immortalize the Pony Express in his memoir Roughing It, described the desolate beauty and stark terror of the region: "The Pony Rider was usually a little bit of a man, and he was an absolute monarch in his own right, in his particular division. His saddle was his throne, his horse his scepter." He further noted the "tremendous solitude" and the "unbroken desert for miles and miles."

Where Man Met the Wilderness – and War

But nature was not the only, or even the most formidable, adversary in Division Three. This was the ancestral land of the Gosiute and Shoshone peoples, tribes whose way of life was increasingly threatened by the encroaching tide of white settlement and the relentless march of westward expansion. The Pony Express, though merely a mail service, was perceived by some as another harbinger of this unwelcome invasion.

The spring and summer of 1860 saw a violent escalation of tensions, often referred to as the "Pony Express War" or the "Gosiute War." Native American warriors, frustrated by broken treaties, land theft, and the disruption of their traditional hunting grounds, saw the isolated stations and riders as legitimate targets. Attacks became frequent and brutal. Stations were burned, stock stolen, and riders killed, their bodies sometimes found scalped and mutilated. This was not random banditry; it was a desperate struggle for survival and sovereignty.

One of the most harrowing periods occurred in May 1860. A series of coordinated attacks devastated the route, particularly in Division Three. Numerous stations were destroyed between Ruby Valley and Schell Creek. Communication was severed. The Pony Express was brought to a standstill. It took the intervention of the U.S. Army, deploying troops from Camp Floyd, Utah, to quell the uprising and restore the mail service. The cost was high, both in lives and in the financial strain on the already struggling company.

The Riders of Renown: "Pony Bob" Haslam

Among the many brave souls who rode Division Three, certain names stand out, their exploits woven into the fabric of the legend. Perhaps none embodies the sheer grit and determination of the Pony Express rider more than Robert "Pony Bob" Haslam. A slight, fearless Englishman, Haslam’s most legendary ride occurred precisely during the height of the Gosiute War.

On May 11, 1860, Haslam arrived at Reed’s Station (near present-day Fallon, Nevada, though part of the wider conflict zone) to find a message that the next station, 12 miles distant, had been attacked and its keeper killed. Undeterred, he pressed on. When he reached the station, he found it burned to the ground. Miraculously, a relief rider was there, ready to take the mochila. But Haslam, seeing the dire situation, volunteered to continue. He rode another 90 miles, dodging arrows and bullets, before finally passing the mail off.

But his ordeal wasn’t over. The next day, realizing the return rider had not made it through the dangerous territory, Haslam mounted a fresh horse and rode back, covering the same perilous 120-mile stretch. In total, over a two-day period, "Pony Bob" rode an astonishing 380 miles through hostile territory, delivering critical dispatches and saving the mail. His extraordinary feat, recognized even at the time, became a powerful testament to the caliber of men who rode Division Three.

Other riders, like William F. "Buffalo Bill" Cody, are famously associated with the Pony Express, though his actual time as a rider was brief and primarily on less dangerous sections. The enduring image, however, is of these young, determined figures, silhouetted against the vast Western sky, racing against time, danger, and the very elements.

The Sunset of a Legend

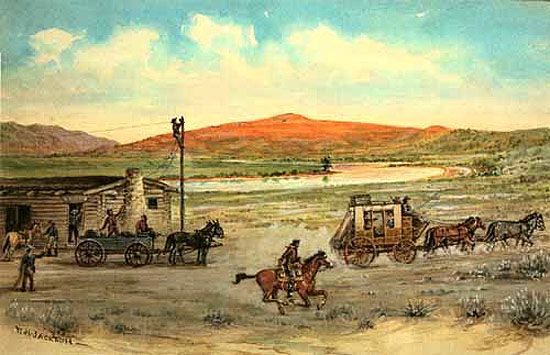

The Pony Express, for all its heroism and daring, was a venture born of necessity and ultimately rendered obsolete by progress. Just 18 months after its first mail pouch left St. Joseph, on October 24, 1861, the transcontinental telegraph line was completed. A message that once took ten days to deliver could now flash across the country in minutes. The age of the horse-powered messenger was over.

Yet, its legacy far outlived its brief existence. The Pony Express proved that a transcontinental route was viable, paving the way for stagecoach lines and railroads. It captured the imagination of a nation, symbolizing American ingenuity, courage, and the relentless drive to conquer the frontier.

Division Three, the most treacherous leg of this epic journey, played an outsized role in shaping this legend. It was here, amidst the shimmering heat and the brutal cold, the silent mountains and the hostile encounters, that the true spirit of the Pony Express was forged. The "ghost riders" of the Great Basin, those young men who risked death daily for a few dollars and the promise of a quicker message, left an indelible mark. Their legend is not just about speed; it’s about an unyielding resolve, a testament to human endeavor against overwhelming odds, and a powerful, enduring symbol of a pivotal moment in American history. They rode into the sunset of the old West, but into the sunrise of an enduring American myth.