Echoes in the Dust: The Unwritten Legends of Kansas’s Indian Wars

America, a nation built on myth and ambition, often curates its legends with a careful hand. We celebrate the intrepid pioneer, the daring cowboy, the westward expansion as an unstoppable march of progress. Yet, beneath the gilded narratives and heroic tales, lie darker, more complex legends – the unwritten stories, the battles fought not for land from a foreign power, but for the very existence of a people against the relentless tide of Manifest Destiny. Nowhere is this tension more palpable, these forgotten legends more vivid, than in the windswept plains of Kansas during the tumultuous Indian Wars.

Kansas, the geographical heart of the nation, became the heart of this conflict. It was a land of transition, a vast canvas where the ancient ways of the Plains tribes – the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Lakota, Kiowa, and Comanche – clashed violently with the surging wave of American settlers, prospectors, and railroad builders. The legends forged here are not merely of military campaigns and strategic victories; they are legends of survival and subjugation, of cultural annihilation and enduring resilience, etched into the very dust and rivers of the state.

The story begins long before the first cavalry charge. For centuries, the Kansas landscape was home to indigenous nations like the Kaw (Kansa), Osage, and Pawnee, who had intricate societies, agricultural practices, and spiritual connections to the land. But by the mid-19th century, these original inhabitants were already being squeezed, their lands ceded under duress, their populations decimated by disease and conflict. The Indian Wars in Kansas, therefore, were not just a clash with the original inhabitants, but often with tribes pushed westward by earlier conflicts, finding themselves in a desperate struggle for their last remaining hunting grounds.

The catalyst for the full-blown conflict was the insatiable hunger for land and resources. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, intended to resolve the slavery question, inadvertently opened a new front in the conflict over land. It created the Kansas Territory, effectively legalizing white settlement in areas previously designated as "Indian Territory" by earlier treaties. This legislative act, more than any single battle, set the stage for the ensuing bloodshed. Settlers, fueled by the belief in Manifest Destiny – the divinely ordained right to expand across the continent – poured into Kansas. They saw a fertile land ripe for farming, a route for railroads, and a resource for buffalo hides. The Plains tribes saw their ancestral lands, their hunting grounds, their very way of life, being systematically dismantled.

The buffalo, central to the Plains tribes’ existence, became an early casualty and a symbol of the impending doom. It provided food, shelter, clothing, tools, and spiritual sustenance. The U.S. government and military leaders understood this vital connection. General William Tecumseh Sherman famously remarked, "The only way to civilize Indians is to kill their buffalo." This sentiment translated into a deliberate policy of extermination. Professional buffalo hunters, encouraged by the government, slaughtered millions, often leaving the carcasses to rot. By 1883, the vast herds that had once darkened the plains were virtually gone, a deliberate strategy to starve the Plains tribes into submission and break their independent spirit. This act of ecological warfare, more than any direct military engagement, solidified the end of an era and became a tragic legend in itself.

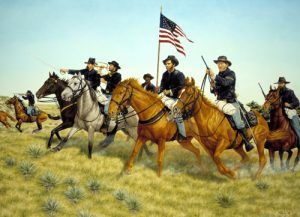

The period between the 1860s and 1870s saw Kansas become a crucible of violence. The Civil War briefly diverted federal attention, but the underlying tensions only festered. With the war’s end, the full might of the U.S. Army, including regiments of cavalry and the famed Buffalo Soldiers (African American soldiers who served on the frontier), turned its focus to "pacifying" the Plains. Figures like General Philip Sheridan, known for his brutal efficiency, became architects of this policy. Sheridan, famously (though controversially) attributed with the quote, "The only good Indian I ever saw was dead," epitomized the harsh prevailing attitude that often viewed Native Americans as obstacles to progress rather than as sovereign peoples.

The legends of Kansas’s Indian Wars are stained by broken treaties. The 1867 Medicine Lodge Treaty, for instance, aimed to confine the Southern Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, Kiowa, and Plains Apache to reservations in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). In exchange for vast tracts of land, the tribes were promised annuities, schools, and protection. Yet, the treaty was signed under duress, often by tribal leaders who did not represent the full will of their people, and its terms were routinely violated by land-hungry settlers and an unresponsive government. This cycle of promise and betrayal fueled a desperate resistance, turning peaceful coexistence into a bitter struggle for survival.

One of the most defining and brutal events, though geographically in Colorado, cast a long shadow over Kansas: the Sand Creek Massacre of November 29, 1864. Colonel John Chivington’s Colorado Volunteers attacked a peaceful village of Cheyenne and Arapaho, under the protection of the U.S. Army, flying an American flag and a white flag of truce. The atrocity resulted in the slaughter of over 150 non-combatants, mostly women, children, and the elderly. The survivors of Sand Creek, many of whom sought refuge with relatives in Kansas, carried with them an indelible trauma and a burning desire for vengeance. This massacre shattered any lingering trust and ignited a series of retaliatory raids across Kansas and Colorado, turning the plains into a blood-soaked battleground.

The legends of Native American resistance are equally compelling. Faced with overwhelming odds, the Plains tribes displayed extraordinary courage, strategic brilliance, and a profound connection to their spiritual beliefs. Leaders like Roman Nose, a Cheyenne warrior revered for his fearlessness and leadership, became legendary figures. Roman Nose’s prowess was vividly demonstrated at the Battle of Beecher Island in September 1868, fought on the Arickaree Fork of the Republican River in present-day Yuma County, Colorado, but with direct implications for Kansas. Here, a small detachment of 50 U.S. Army scouts, led by Major George Forsyth, found themselves surrounded by an estimated 600-700 Cheyenne and Sioux warriors. Despite being pinned down for days, suffering heavy casualties, and eventually losing Roman Nose, the Native forces demonstrated remarkable tactical skill and determination, nearly wiping out Forsyth’s command. This siege became a legend of frontier heroism for the scouts, but for the Cheyenne, it was a testament to their fierce defense of their way of life, even in the face of insurmountable odds.

Kansas also witnessed the raids that terrorized settlers and led to further military campaigns. The Saline Valley raids and the Plum Creek Massacre of 1868, for instance, saw Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors strike back at encroaching settlements, demonstrating the tribes’ desperation and their ability to inflict significant damage. These raids, often targeting isolated homesteads and stagecoach lines, fueled public demand for harsh retaliation and became part of the settler legend of a dangerous, untamed frontier.

The winter campaigns of General Sheridan and Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, particularly the Washita River Massacre in November 1868 (also in present-day Oklahoma, but against tribes operating in Kansas), further escalated the conflict. Custer’s surprise attack on Black Kettle’s Cheyenne village, killing the chief who had survived Sand Creek and many of his people, solidified his controversial legacy and became another dark legend of American military might against a vulnerable population.

By the early 1870s, the writing was on the wall. The Red River War of 1874-75, a series of military engagements against the Southern Plains tribes, effectively ended their independent existence. The last holdouts, starved and weary, were forced onto reservations. The buffalo were gone, the land settled, and the traditional way of life eradicated. The legend of the free-roaming Plains Indian, master of the buffalo hunt, gave way to the tragic legend of the "vanishing Indian," confined and dispossessed.

The legends of Kansas’s Indian Wars are a vital, often uncomfortable, part of the American story. They are not merely tales of conflict, but profound narratives about the collision of cultures, the brutality of expansion, and the enduring human spirit. They remind us that history is rarely clean, and that progress for some often comes at an unimaginable cost to others. The winds that sweep across the Kansas plains today still whisper these stories – of the Pawnee and Kaw, of the Cheyenne and Arapaho, of the soldiers and the settlers. To truly understand the legends of America, we must listen to these echoes in the dust, acknowledge the full spectrum of experiences, and honor the memory of all who lived and died on this contested ground. Only then can we move beyond romanticized myths to a more honest and complete understanding of our shared past.