The Whispers of the Prairie: Unearthing the Legend of Prairie Dog Creek

America, a nation forged in the crucible of ambition and conflict, is a vast repository of legends. From the stoic heroism of its founding fathers to the wild individualism of the frontier, these stories, both grand and grim, shape our understanding of who we are. Yet, for every widely celebrated saga, there exist countless others, equally potent, that lie half-buried beneath the dust of time, their echoes faint but insistent. One such legend, often overshadowed by the more famous clashes of the Indian Wars, is the Battle of Prairie Dog Creek, fought on the sun-baked plains of Kansas in August 1864. It is a tale not just of cavalry charges and desperate resistance, but of a nation wrestling with its own destiny, a clash of cultures that carved the very identity of the American West.

The year 1864 was a tumultuous one for the United States. The Civil War raged with ferocious intensity, consuming the nation’s attention and resources. Grant was grinding down Lee in Virginia, Sherman was marching through Georgia, and the very future of the Union hung precariously in the balance. Yet, even as brother fought brother in the East, another, equally brutal, conflict was unfolding on the Western frontier. Here, the inexorable tide of Manifest Destiny, the belief in America’s divinely ordained right to expand westward, was colliding head-on with the ancient way of life of the Plains tribes – the Lakota Sioux, the Cheyenne, and the Arapaho – who had called these vast, open lands home for centuries.

The westward migration, fueled by the promise of gold, land, and a new beginning, had intensified dramatically in the preceding decades. Wagon trains snaked across the prairies, railroads pushed relentlessly into tribal hunting grounds, and buffalo herds, the very lifeblood of the Plains Indians, were dwindling under the onslaught of hide hunters. Treaties, often signed under duress or misunderstood, were routinely broken by the encroaching settlers and the federal government. Tensions simmered, then boiled over. Raids on wagon trains and frontier settlements became more frequent, often met with brutal retaliation from the U.S. Army. The stage was set for an inevitable, tragic confrontation.

Enter Brigadier General Alfred Sully, a seasoned Union officer who, despite his service in the Civil War, found himself commanding a force of Iowa and Minnesota cavalry, along with a battery of artillery, deep in the heart of what was then an untamed wilderness. Sully’s mission was clear: to chastise the "hostile" Indians, secure the emigrant routes, and push the tribes further west, clearing the path for settlement. His expedition, a punitive force of over 2,000 men, had been marching for weeks, enduring the scorching summer heat and the vast, featureless landscape of the Great Plains. They were on the hunt, and the quarry was a large encampment of Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho, reportedly gathered for a summer buffalo hunt and to discuss the growing threat to their lands.

On August 21, 1864, Sully’s scouts reported a large gathering of Native Americans near a feature known as Prairie Dog Creek, a tributary of the Republican River in what is now Norton County, Kansas. The name itself, "Prairie Dog Creek," evokes the rugged, unassuming nature of the landscape – a place where the earth itself seemed to breathe with the burrowing life of countless rodents. Yet, on this day, the peaceful burrows would bear witness to a fierce and bloody struggle.

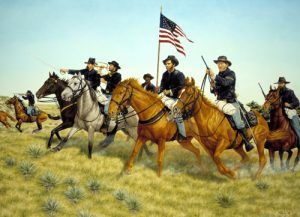

What followed was a classic frontier battle, a dramatic clash of vastly different military doctrines and worldviews. Sully, with his disciplined cavalry and potent artillery, represented the cutting edge of military technology and organization. His troops, many of them veterans of Civil War battles, were trained in linear tactics, cavalry charges, and the devastating power of their howitzers. The Plains warriors, on the other hand, fought with a profound knowledge of their land, utilizing their superior horsemanship, hit-and-run tactics, and the element of surprise. Their primary weapons were bows, lances, and a growing number of firearms acquired through trade or previous skirmishes.

As Sully’s command approached, the Native American warriors, numbering perhaps a thousand or more, quickly formed up, their war cries echoing across the prairie. The initial engagement was a series of skirmishes, with the warriors attempting to draw the cavalry into ambushes within the ravines and gullies that crisscrossed the terrain. One observer noted the sheer audacity and skill of the Native American horsemen: "They rode with incredible speed and agility, sometimes hanging from the sides of their horses, firing arrows and dodging bullets, a blur against the horizon."

Sully, however, was no novice. He deployed his troops in a long skirmish line, gradually pushing the warriors back. His artillery proved particularly effective, the exploding shells sowing terror and disruption among the massed horsemen. The warriors, despite their bravery, had no answer for the concentrated firepower of the howitzers, which could fell multiple riders and horses with a single blast. The battle raged for hours under the relentless August sun. Cavalry charges were met with fierce resistance, and the fighting often devolved into desperate hand-to-hand combat.

"The prairie was alive with flashing steel and smoke," an account from a soldier described, "the air filled with the shouts of men, the screams of horses, and the incessant crack of rifles." The Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors, fighting to defend their families and their way of life, displayed incredible courage. They charged directly into the Union lines, attempting to break their formation, but Sully’s troops held firm, their discipline honed by the crucible of the Civil War.

As the day wore on, Sully executed a flanking maneuver, sending a portion of his cavalry to envelop the Native American positions. This tactical move, combined with the relentless pressure of the artillery, began to turn the tide. Faced with overwhelming firepower and the threat of being encircled, the warriors, having made a valiant stand, eventually began to withdraw, covering the retreat of their women and children, who had been observing the battle from a distance.

The exact casualties of the Battle of Prairie Dog Creek are, like many frontier engagements, difficult to ascertain with precision. Sully’s official reports claimed relatively few losses for his own command, though this often understated the true cost. Native American casualties, however, were undoubtedly significant, with estimates ranging from dozens to well over a hundred killed and wounded. For the Plains tribes, this was not just a military defeat, but a deeply personal loss, impacting their collective memory and further fueling their resentment against the encroaching white settlers.

In the immediate aftermath, Sully declared a victory, having "chastised" the Indians and driven them from the area. However, the battle was far from a decisive blow in the larger scheme of the Indian Wars. It was merely another brutal chapter in a conflict that would rage for decades. The tribes, though wounded, were not broken. They would continue their struggle, driven by a fierce determination to protect their ancestral lands and their diminishing way of life. The battle highlighted the grim reality that even when fighting a Civil War, the United States was simultaneously engaged in another, equally vital, and often more brutal, conflict on its frontier.

The legend of Prairie Dog Creek, while perhaps not as widely known as the Little Bighorn or Wounded Knee, holds a significant place in the tapestry of American history. It represents the grinding, often anonymous, nature of the frontier wars. It was not a battle that produced a Custer or a Sitting Bull of singular legendary status, but rather a collective legend of desperate resistance against overwhelming odds, and the inexorable march of a nation’s expansion. It is a legend whispered by the winds that sweep across the Kansas plains, a story etched into the very soil where blood was shed.

This battle, like so many others, serves as a stark reminder of the immense human cost of westward expansion. It forces us to confront the uncomfortable truths of American history – the displacement, the violence, and the clash of incompatible visions for the future of the continent. The plains of Kansas, once teeming with buffalo and the vibrant life of the Native American tribes, became a stage for this epic, tragic drama.

Today, Prairie Dog Creek remains a largely unmarked landscape, its historical significance known mostly to dedicated historians and local enthusiasts. There are no grand monuments, no bustling visitor centers. Yet, for those who take the time to seek it out, to stand on those quiet plains and listen to the whispers of the wind, the legend of Prairie Dog Creek comes alive. It speaks of the tenacity of the human spirit, the courage of those who fought to defend their homes, and the enduring legacy of a nation built upon both noble ideals and painful realities. It is a legend that compels us to remember that the story of America is not just a tale of triumph, but a complex narrative interwoven with sacrifice, struggle, and the indelible marks left by every battle fought on its vast and storied land. And in its quiet power, Prairie Dog Creek stands as a testament to the legends that shape us, even the ones we are still learning to fully comprehend.