The Ghost of Saline River: Custer’s Near Miss and the Unwritten Legend of the Plains

America’s vast and varied landscape is a canvas for countless legends – tales of pioneering courage, desperate struggles, and the forging of a nation. From the misty mountains of the Appalachians to the sun-baked deserts of the Southwest, these stories often speak of heroic deeds, epic battles, or the enduring spirit of those who shaped the frontier. Yet, some of the most profound legends are not of what did happen, but of what almost did. They are the whispers of a different destiny, a path not taken, a battle unfought that nonetheless cast a long shadow over the future.

One such legend, less heralded but deeply significant, is etched into the sun-drenched plains of Kansas, along the unassuming banks of the Saline River. It’s a story intimately tied to the meteoric rise and tragic fall of one of America’s most polarizing figures, George Armstrong Custer, and a moment in August 1867 when a potential massacre, or a decisive victory, hung in the balance. The Battle of Saline River, or rather, the non-battle of Saline River, offers a haunting glimpse into the brutal realities of the Plains Wars and the complex choices made under immense pressure.

The Crucible of the Plains: A Nation in Motion

The year 1867 found America still reeling from the scars of the Civil War, yet inexorably drawn westward. Manifest Destiny, the belief in the nation’s divinely ordained expansion across the continent, fueled a relentless push into the territories. Railroads, symbols of progress and connection, snaked their way across the prairies, bringing settlers, industry, and an irreversible tide of change. But these lands were not empty; they were the ancestral homes of powerful Native American nations – the Cheyenne, Sioux, Arapaho, and others – whose way of life was inextricably linked to the buffalo and the vast open spaces.

The clash was inevitable, brutal, and often misunderstood. The U.S. Army, a force largely comprised of Civil War veterans, was tasked with protecting the railroad crews, safeguarding settlers, and "pacifying" the Native American tribes. This was a war of attrition, cultural annihilation, and often, sheer survival for both sides. The soldiers, many fresh from the horrors of Shiloh or Gettysburg, now faced a new, elusive enemy, masters of guerrilla warfare on their home turf.

Enter Custer: The Boy General on the Frontier

At the heart of this unfolding drama was George Armstrong Custer. A flamboyant and ambitious cavalry officer, Custer had rocketed to fame during the Civil War, earning the moniker "Boy General" for his daring charges and youth. By 1867, still only 27, he commanded the newly formed 7th U.S. Cavalry, a regiment destined for both glory and infamy. Custer was a figure of contradictions: immensely brave, undeniably charismatic, yet prone to recklessness and a craving for personal glory that often overshadowed prudence.

His initial assignment to the Western frontier was a rude awakening. The disciplined tactics of the Civil War were ill-suited to chasing elusive war parties across endless plains. Supplies were scarce, the climate harsh, and the enemy often invisible until it was too late. Custer’s early months on the frontier were marked by frustration, desertions, and a growing understanding of the unique challenges posed by the Plains Indians. He was learning, often painfully, that the West was a different beast entirely.

The Summer of 1867: A Tense Patrol

The summer of 1867 saw Custer and his 7th Cavalry engaged in arduous patrols across western Kansas, attempting to locate and engage hostile Native American bands. The heat was oppressive, water scarce, and the men and horses constantly pushed to their limits. Rumors of large encampments and recent raids on settlers and railroad workers fueled the urgency of their mission.

On July 31, Custer’s command, exhausted and low on supplies, camped near the forks of the Saline River. Their mission was to protect construction gangs of the Kansas Pacific Railroad and retaliate for recent raids. The scouts, including the renowned frontiersman William F. "Buffalo Bill" Cody, were out ranging wide, looking for any sign of the enemy. The air was thick with tension; everyone knew they were in hostile territory.

The Discovery: A Sea of Tipis

Then came the report that would forever etch the Saline River into Custer’s personal legend. Early on August 1, 1867, Custer’s scouts returned with astonishing news: they had discovered a massive Native American encampment. Not just a raiding party, but a vast village, stretching for miles along the riverbanks, an estimated 6,000 to 8,000 warriors, women, and children, representing a formidable alliance of Cheyenne, Sioux, and Arapaho. The sheer scale of it was almost incomprehensible.

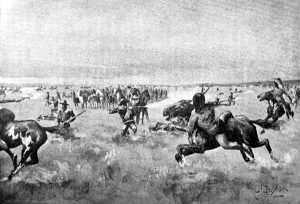

Custer, ever eager for a fight, rode forward to verify the report himself. What he saw must have been both exhilarating and terrifying. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of tipis dotted the landscape, their smoke rising lazily into the morning sky. Herds of ponies grazed nearby, and the sounds of a vibrant, powerful community drifted across the plains. This was no small band; this was a significant portion of the fighting strength of the Southern Plains tribes, gathered for summer councils, hunts, and perhaps, to prepare for war.

The Dilemma: Attack or Retreat?

Here lies the heart of the Saline River legend: Custer’s agonizing dilemma. His entire career had been defined by aggressive action, by leading from the front, by charging into the fray regardless of the odds. His instinct, his reputation, and the very nature of cavalry warfare demanded an attack. A decisive victory here could break the back of Native American resistance on the Southern Plains, cement his fame, and perhaps even pave his way to higher command.

But the reality of the situation was stark. His command, the 7th Cavalry, numbered only around 400 men. They were exhausted, low on ammunition, and far from any support. To attack such a massive force, perhaps 15 to 20 times their number, would have been suicidal. It would not have been a battle; it would have been a massacre, with Custer’s command likely annihilated.

This was a moment of profound personal crisis for the "Boy General." As historian Robert M. Utley noted in Cavalier in Buckskin: George Armstrong Custer and the Western Military Frontier, Custer "was not the kind of officer to shrink from a fight, but this was a force so overwhelmingly superior that even his vaunted courage must have faltered."

Against every fiber of his being, against the very image he had carefully cultivated, Custer made a decision that surprised many: he chose not to attack. Instead, he ordered a slow, careful retreat under the cover of darkness.

The Retreat and the Skirmish that Wasn’t the Battle

The retreat was fraught with tension. The Cheyenne and Sioux scouts, always vigilant, had likely spotted the American cavalry. The expectation of an attack, or at least a pursuit, must have been overwhelming for Custer’s men. Yet, surprisingly, the main body of Native American warriors did not immediately pursue. Perhaps they, too, were surprised by the cavalry’s sudden appearance and withdrawal, or perhaps they were wary of an ambush.

It’s important to clarify a common point of confusion: while Custer did not engage the main encampment, there was a minor skirmish that day involving Major George Forsyth’s independent company of scouts, who were operating nearby. Forsyth’s men, perhaps numbering around 50, briefly engaged a small party of warriors. This minor engagement, however, was a far cry from the full-scale battle that could have erupted between Custer’s 7th Cavalry and the massive encampment. The "Battle of Saline River" is, in its truest sense, the colossal clash that was averted.

Custer’s command successfully disengaged, though the retreat was marked by fear, thirst, and the near-mutiny of some soldiers who, demoralized and exhausted, threatened to desert. Custer, showing a different kind of courage, personally confronted and disarmed several of these men.

The Aftermath: Criticism and a Glimpse of Prudence

News of Custer’s decision to retreat from such a large force was met with mixed reactions. Some, particularly his superiors, saw it as a prudent and responsible act, saving his command from certain destruction. Others, especially those who believed in a more aggressive policy against Native Americans, criticized him for lacking the "courage" to engage. The whispers of "cowardice" were undoubtedly painful for a man who thrived on valor.

Yet, in retrospect, the decision at Saline River stands as one of Custer’s most rational and disciplined moments on the frontier. It demonstrated a rare flash of prudence, a momentary triumph of tactical assessment over his innate impulsiveness. It was a choice that saved hundreds of lives, though it ran contrary to the very legend he was so carefully constructing around himself.

The Unwritten History: A Different Future?

The legend of Saline River is not of a heroic charge or a decisive victory, but of a profound "what if." What if Custer had attacked? The outcome would almost certainly have been catastrophic for the 7th Cavalry. An annihilation at Saline River in 1867 would have profoundly altered the course of the Plains Wars. Would another commander have taken his place? Would the defeat have spurred even harsher retribution from the U.S. Army?

Conversely, what if Custer had somehow, miraculously, won a great victory? It would have been a triumph of unparalleled scale, perhaps bringing a quicker, if no less tragic, end to Native American resistance on the Southern Plains.

The Saline River, therefore, stands as a silent monument to a moment of averted destiny. It highlights the immense power of the Plains tribes when united and concentrated, and the perilous choices faced by American military commanders on the frontier. It also offers a rare instance where Custer, the legend of Little Bighorn, chose caution over glory, a decision that has largely been overshadowed by his more infamous final stand.

Legacy of a Near Miss

The Battle of Saline River, though it never truly happened as a full-scale engagement, remains a crucial, if often forgotten, chapter in the American West. It serves as a reminder that legends are not just forged in the heat of battle, but also in the moments of agonizing decision-making, in the silent retreats, and in the "what ifs" that haunt the historical record.

For the Native American tribes, the Saline River represented a moment of strength, a powerful gathering that demonstrated their continued presence and resistance, even as the tide of American expansion relentlessly pushed against them. For Custer, it was a moment of stark realization, a lesson in humility and the limits of audacity, a lesson that perhaps he eventually forgot on that fateful day nine years later at the Little Bighorn.

The ghost of Saline River lingers, a testament to the brutal complexities of the American frontier, a silent legend whispering of the battles that almost were, and the profound impact of the choices made, or not made, on those vast, unforgiving plains. It reminds us that sometimes, the most significant events are those that were narrowly avoided, leaving us to ponder the countless alternate histories that might have been.