Echoes from the Mogollon Rim: The Forgotten Legend of Big Dry Wash

America is a tapestry woven with countless legends, tales whispered across generations, often born from the clash of cultures, the struggle for survival, and the unforgiving embrace of the frontier. From the stoic heroism of the Alamo to the tragic grandeur of Little Bighorn, these stories form the bedrock of a national identity. Yet, tucked away in the rugged, sun-baked canyons of Arizona, there lies a legend less frequently recounted, a pivotal, brutal encounter that, while lacking the widespread fame of its counterparts, carved a definitive line in the sand of the American West: the Battle of Big Dry Wash.

It was July 1882, and the Arizona Territory was a crucible of conflict. For decades, the Apache, fierce and proud guardians of their ancestral lands, had resisted the relentless encroachment of settlers and the iron fist of the U.S. Army. Broken treaties, forced relocations to barren reservations, and the relentless pressure on their traditional way of life had fueled a cycle of violence that seemed unending. Bands of Apache, driven by desperation and a thirst for freedom, frequently broke away from the reservations, earning the infamous label of "renegades." These warriors, intimately familiar with every rock and ravine of their homeland, launched devastating raids, often disappearing into the vast, labyrinthine landscape as quickly as they appeared.

The spark that ignited the chase leading to Big Dry Wash was not a singular event, but a culmination of escalating tensions. The previous year, 1881, had seen the tragic "Cibecue Creek Incident," where a medicine man, Nakaidoklini, was killed by soldiers, leading to a mutiny by Apache scouts and the murder of six officers, including Captain Edmund Hentig. This event, followed by further unrest and the escape of various Apache groups, galvanized the Army. Among the most active and elusive of these "renegade" bands was one led by Na-tio-tish, a skilled warrior who, along with his followers, had terrorized the central Arizona corridor, striking fear into the hearts of settlers and prospectors. They were responsible for several murders and raids, including the killing of Colonel George W. Tiffany of the Arizona Territorial Militia. The Army, under the command of General Irvin McDowell, was determined to put an end to their depredations.

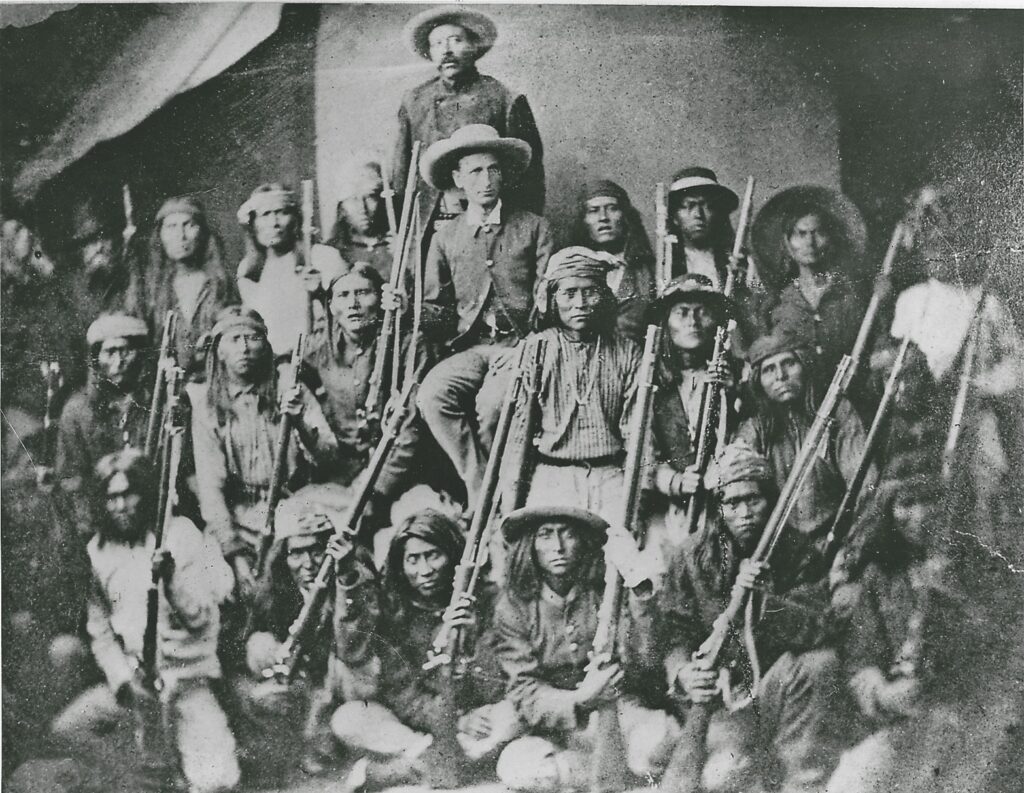

The pursuit of Na-tio-tish’s band was a testament to the brutal realities of frontier warfare. The Arizona landscape itself was a formidable adversary: scorching summer heat, treacherous canyons, dense chaparral, and water scarcity. The terrain was so unforgiving that it seemed to swallow entire companies of men. However, the U.S. forces had a secret weapon, one that would prove indispensable in this particular engagement: Apache scouts. These men, often from rival bands or those who had chosen to align with the Army, possessed an unparalleled knowledge of the land and an almost supernatural ability to track. Among them was the legendary Al Sieber, Chief of Scouts, a man whose exploits were already the stuff of frontier myth. Sieber, a grizzled veteran of countless skirmishes, understood the Apache way of fighting better than almost any white man, and his leadership of the scouts was crucial.

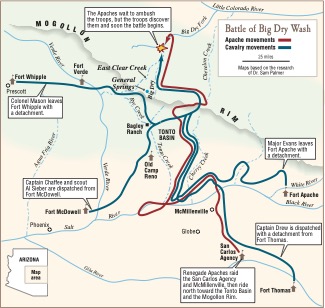

On July 6, 1882, a combined force of approximately 100-150 cavalrymen from the 3rd and 6th U.S. Cavalry regiments, along with a contingent of Apache scouts, set out from Fort Apache. The command was under the leadership of Captain Adna R. Chaffee, a seasoned officer who would later rise to become Chief of Staff of the Army. Their mission: find Na-tio-tish and his warriors, and bring them to justice. The chase was relentless, a grueling trek through some of the most difficult terrain imaginable. The scouts, led by Sieber and Lieutenant Thomas Cruse, picked up the faint trail, following it for days through the Mogollon Rim country, a vast escarpment characterized by steep cliffs and deep, forested canyons.

As they pressed deeper into the wilderness, the signs became clearer. The Apache, confident in their defensive position and the natural strength of the land, had grown less cautious. On the morning of July 17, after an arduous, all-night march, Lieutenant Cruse, leading the advance with his Apache scouts, spotted the "renegade" camp. Na-tio-tish and his warriors had chosen a seemingly impregnable position high on a mesa, overlooking a deep, forested canyon later known as Big Dry Wash (or sometimes called the Battle of Chevelon Fork or General Springs). The mesa was surrounded on three sides by sheer, inaccessible cliffs, with the only approach being a narrow, heavily timbered ridge. From their vantage point, the Apache felt secure, believing they could easily spot and repel any attacking force.

Captain Chaffee, upon receiving Cruse’s report, recognized the gravity of the situation and the opportunity it presented. A frontal assault would be suicidal. Instead, he devised a daring plan: a classic pincer movement. While one detachment, led by Lieutenant George P. Morgan, would feign a frontal attack to draw the Apache’s attention, the main body of troops, guided by Sieber and Cruse, would attempt to outflank the enemy by navigating a perilous, circuitous route through the dense forest and up a steep, hidden path to gain the mesa from the rear. It was a high-risk maneuver that relied heavily on stealth, surprise, and the exceptional abilities of the Apache scouts.

The flanking movement was executed with remarkable precision. The soldiers, moving silently through the thick pine and juniper, painstakingly climbed the difficult terrain, their every step a testament to their discipline and determination. As Morgan’s men began their diversionary fire, drawing the Apache’s attention and return fire, Chaffee’s main force, having reached their position, unleashed a devastating volley from the rear. The surprise was absolute. "The Apache were caught completely off guard," wrote historian Dan L. Thrapp. "Their defensive position, so strong against a frontal assault, became a trap."

Chaos erupted in the Apache camp. Warriors, who moments before had been confidently returning fire, suddenly found themselves caught between two relentless forces. The battle quickly devolved into a desperate, close-quarters fight amidst the trees and rocks. Na-tio-tish, the defiant leader, was among the first to fall, shot down early in the engagement. His death shattered the Apache’s command structure and their morale. Despite their courage and intimate knowledge of the terrain, they were overwhelmed. Some warriors attempted to escape by scrambling down the sheer cliffs, only to be picked off by soldiers or fall to their deaths.

The battle raged for several hours, a brutal, unforgiving struggle. By the time the firing ceased, the victory for the U.S. forces was decisive. Army casualties were remarkably light: three soldiers killed and four wounded. For the Apache, the cost was devastating. Estimates vary, but between 16 and 27 warriors were killed, including Na-tio-tish, and many more were wounded. Twenty-three women and children were captured. The band was effectively broken, their fighting spirit crushed.

The Battle of Big Dry Wash marked a profound turning point in the Apache Wars, particularly in Arizona. It was the last major engagement between the U.S. Army and a large, organized band of Apache warriors in the territory. While sporadic fighting and the campaigns against Geronimo would continue for several more years, those were primarily hit-and-run tactics by smaller, fragmented groups. Big Dry Wash signaled the end of large-scale Apache resistance in the region. The Army’s successful use of Apache scouts, and the tactical brilliance displayed by Chaffee and Sieber, further cemented a strategy that would prove instrumental in future campaigns.

Why then, does Big Dry Wash not occupy the same prominent place in American historical memory as other frontier battles? Perhaps it is due to its remote location, far from major population centers or the eager pens of eastern journalists. Perhaps it was overshadowed by the more dramatic, though ultimately less decisive, campaigns against Geronimo that followed. Or perhaps, in the grand narrative of westward expansion, the defeat of a relatively smaller band of "renegades" simply didn’t carry the same weight as a Custer’s Last Stand.

Yet, the legend of Big Dry Wash endures for those who delve into the annals of the American West. It is a legend etched not in grand monuments but in the rugged landscape itself – in the whispering pines of the Mogollon Rim, the silent canyons that bore witness to the fierce struggle, and the dusty ground where courage and desperation met. It stands as a somber testament to the end of an era, a final, bloody chapter in the long, tragic conflict between the Apache and a burgeoning nation. It reminds us that every corner of America holds its own profound, often forgotten, legends – tales of sacrifice, strategy, and the enduring human spirit, waiting to be rediscovered and remembered.