The Unwritten Chapters: Utopian Dreams in the Legends of America

America, a land forged in revolution and steeped in the spirit of boundless possibility, is a nation rich with legends. From the towering tales of Paul Bunyan and the industrious Johnny Appleseed to the rugged individualism of Davy Crockett and the mystique of the Wild West, these narratives form the bedrock of a collective identity, shaping our understanding of who we are and what we aspire to be. Yet, beyond the frontiersmen and folklore creatures, lies another, often overlooked, stratum of American legend: the relentless pursuit of utopia, the audacious belief that a perfect society could be engineered from scratch. And nowhere is this legend more vividly, and poignantly, etched into the landscape than in the quiet, historic town of New Harmony, Indiana.

The tapestry of American legends is woven with threads of diverse origins. There are the mythological figures, like the gargantuan lumberjack Paul Bunyan, whose blue ox, Babe, carved out lakes and rivers with a swish of his tail, embodying the colossal scale of the American landscape and the immense labor required to tame it. Then there are the historical figures, elevated to legendary status through deeds and embellishments: George Washington, the stoic father of the nation, forever linked to the cherry tree anecdote symbolizing his unwavering honesty; or Paul Revere, whose midnight ride became a symbol of vigilance and nascent American defiance. These are tales of courage, ingenuity, and a pioneering spirit that pushed boundaries, both geographical and psychological.

The Wild West, too, has gifted America a pantheon of legends – outlaws like Jesse James, lawmen like Wyatt Earp, and the iconic "Buffalo Bill" Cody, whose frontier show captivated audiences worldwide. These stories, often romanticized and exaggerated, speak to a period of rapid expansion, lawlessness, and the forging of new societal norms in the vast, untamed territories. They underscore themes of freedom, self-reliance, and the eternal struggle between good and evil on a sprawling, unforgiving stage. Even the more contemporary legends, from the elusive Bigfoot lurking in the Pacific Northwest to the mysterious lights of Roswell, New Mexico, speak to an enduring fascination with the unknown and the desire to believe in something beyond the mundane.

But beneath these tales of individual heroism and frontier grit lies a deeper, perhaps more fundamental American legend: the quest for a better way of life, the relentless pursuit of an ideal society. This is the legend of the American Dream itself – the belief that through hard work and determination, anyone can achieve prosperity and happiness. This dream, however, wasn’t always just about individual success; for many, it encompassed a communal vision, a collective yearning for a perfect social order. This is where New Harmony, Indiana, enters the narrative, not as a legend of individual achievement, but as a legend of collective aspiration, a grand social experiment that tested the very limits of human nature and societal design.

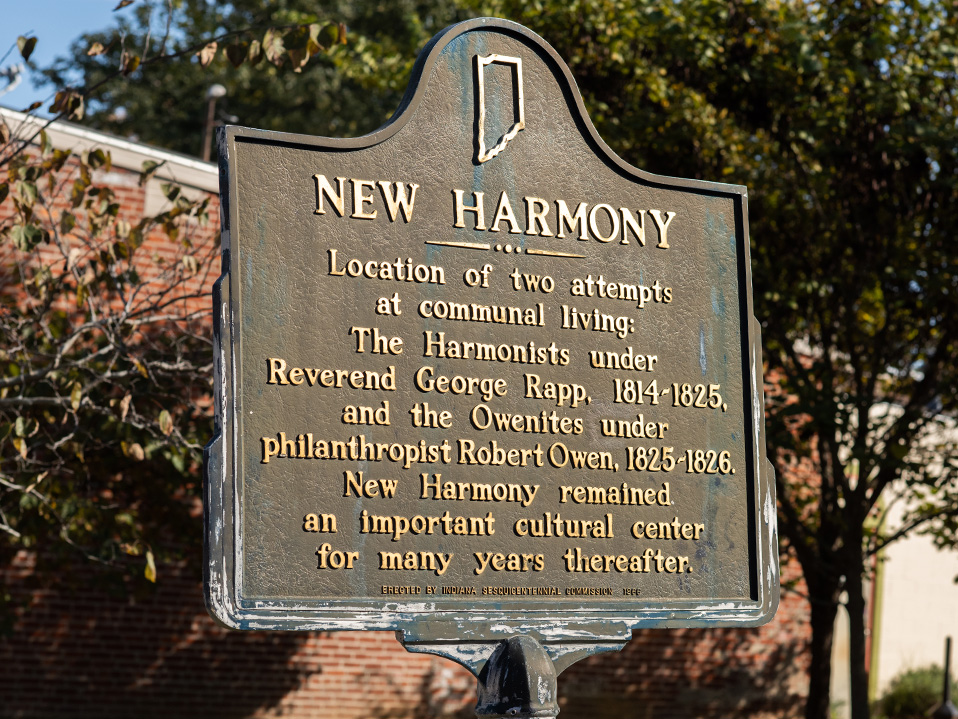

Nestled on the Wabash River, New Harmony’s story begins in 1814 with the arrival of the Harmonists, a devout German Pietist sect led by the charismatic George Rapp. These were not mere settlers; they were idealists, driven by a profound spiritual conviction and the belief that they could establish a communal society, the "Harmonie Society," in anticipation of Christ’s second coming. Their vision was radical for its time: communal ownership of property, celibacy, and a rigorous work ethic, all bound by a shared faith.

The Harmonists were incredibly industrious. In just ten years, they transformed a wilderness into a thriving town, constructing over 180 buildings – brick houses, factories, a church, and even a labyrinth, symbolizing the winding path to spiritual perfection. Their agricultural and industrial endeavors flourished, producing wool, cotton, and grain, making them remarkably self-sufficient and prosperous. "They built a legend of disciplined faith and material success," notes one historical account, "a testament to what communal living, driven by a singular purpose, could achieve." Their structures, many of which still stand today, are not just buildings; they are physical manifestations of a legend of unwavering faith and communal effort. The Harmonist Cemetery, with its unmarked graves, further underscores their belief in equality in death, as in life.

However, the Harmonists, despite their success, felt a calling to relocate, eventually selling their entire town in 1825 for a substantial sum of $125,000. Their buyer was Robert Owen, a Welsh industrialist and social reformer whose name would become synonymous with utopian socialism and New Harmony’s second, even more famous, social experiment. Owen’s vision was entirely secular, yet no less ambitious. He believed that human character was not innate but shaped by environment, famously stating, "Man is the creature of circumstances." His aim was to create a "New Moral World" in which education, science, and communal living would foster enlightened, cooperative citizens, free from the vices of poverty and ignorance.

Owen’s arrival was heralded by what became known as the "Boatload of Knowledge." In January 1826, a keelboat arrived carrying an extraordinary collection of intellectuals, scientists, educators, and artists – among them geologist William Maclure, educator Joseph Neef, and naturalists Thomas Say and Charles-Alexandre Lesueur. This legendary gathering of minds, arguably one of the most concentrated collections of intellectual talent in early America, aimed to establish a society founded on rational principles and universal education. They envisioned a community where children received free, progressive education from infancy, where labor was shared, and property was held in common.

The Owenite experiment, however, was short-lived and ultimately unsuccessful. Within two years, the community dissolved amidst ideological disputes, a lack of clear leadership, and the inherent challenges of human nature clashing with lofty ideals. Robert Owen himself eventually returned to Great Britain, acknowledging the difficulties of implementing such a radical social system. Yet, despite its economic and social failure, the Owenite period etched another layer onto New Harmony’s legend. It became a legend of noble failure, a testament to the audacious courage of those who dared to dream of a better world, even if their dreams proved too far ahead of their time. The "Boatload of Knowledge" left an indelible mark on American science and education, with many of its members going on to make significant contributions in their respective fields across the nascent nation. The very idea of communal education, for instance, pioneered here, would influence later reform movements.

Today, New Harmony is a living museum, a quiet, picturesque town that continues to grapple with its extraordinary past. Its preserved Harmonist buildings stand as stoic reminders of faith and industry, while the sites of Owen’s ambitious experiment whisper tales of intellectual fervor and the fragility of human perfectibility. The town embraces its dual legacy, offering visitors a unique glimpse into two distinct, yet equally legendary, American utopian attempts. The Roofless Church, designed by renowned architect Philip Johnson, stands as an interdenominational symbol of universal faith, reflecting the spiritual openness that New Harmony embodies. The Atheneum, designed by Richard Meier, serves as a visitor’s center, a modern architectural marvel that guides one through the town’s historical layers. Even Tillich Park, named after the theologian Paul Tillich who found inspiration here, adds to the town’s enduring aura as a place of profound thought and spiritual contemplation.

New Harmony, Indiana, may not boast tales of mythical beasts or gun-slinging heroes, but its legend is arguably more profound. It is the legend of America’s enduring capacity for self-reinvention, for questioning existing norms, and for daring to imagine a society built on radically different principles. It stands as a testament to the power of human aspiration – the unwavering belief that a better world is not just possible, but achievable, even if the path to it is fraught with challenges.

In the grand tapestry of American legends, New Harmony occupies a unique and vital space. It reminds us that our legends are not solely about conquering frontiers or individual triumphs, but also about the relentless, sometimes heartbreaking, pursuit of collective ideals. It is a legend of two communities, bound by the common thread of hope, who sought to write new chapters in the American story – chapters where perfect harmony, whether spiritual or secular, was not just a dream, but an achievable reality. And as visitors walk its quiet streets, they are reminded that the legend of America continues to be written, one bold experiment and one audacious dream at a time.