The Unbroken Trail: The Epic Migration of the Nez Perce

By [Your Name/Journalist’s Name]

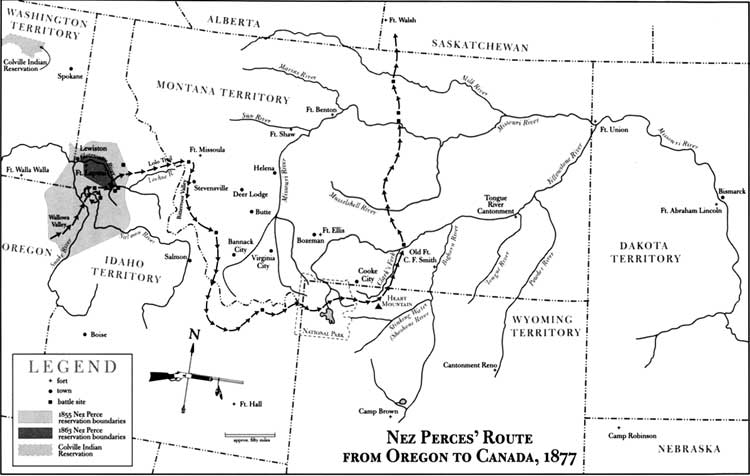

In the annals of American history, few sagas resonate with the raw power and tragic beauty of the Nez Perce War of 1877. It was not a conventional war in the European sense, but an epic flight for survival, an extraordinary 1,170-mile odyssey across some of North America’s most rugged terrain. For 118 days, a small band of fewer than 800 Nez Perce, including women, children, and elders, outmaneuvered, outfought, and outwitted several U.S. Army commands, led by brilliant military strategists like Chief Joseph, Looking Glass, and Ollokot. Their desperate migration, born of broken promises and a fierce love for their ancestral lands, etched an indelible mark on the American consciousness, symbolizing both the resilience of Indigenous peoples and the brutal cost of westward expansion.

To understand the Nez Perce migration, one must first grasp the deep roots of their connection to the land. Known as the Nimiipuu, "The People," they traditionally inhabited a vast territory spanning parts of present-day Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and Montana. Their lives were intimately intertwined with the cycles of nature: salmon runs in the Clearwater and Snake Rivers, camas root harvests in the fertile meadows, and seasonal buffalo hunts across the Bitterroot Mountains. They were horse breeders of renown, their Appaloosa horses legendary for their strength and beauty, facilitating their wide-ranging migrations and trade networks. Their encounters with Lewis and Clark in 1805 were marked by hospitality and mutual respect, setting a precedent of peace that lasted for decades.

However, the tide began to turn with the relentless surge of American settlers. The discovery of gold in Nez Perce territory in 1860 brought an uncontrollable influx of prospectors, squatters, and disease. The U.S. government, eager to appease the encroaching population, initiated a series of treaties that progressively chipped away at the Nimiipuu’s domain. The Treaty of 1855 had established a large reservation, encompassing much of their traditional lands. But the Treaty of 1863, dubbed the "Thief Treaty" by the Nez Perce, drastically reduced their reservation by nearly 90 percent, shrinking it to a fraction of its original size.

Crucially, this latter treaty was signed by only a minority of the Nez Perce chiefs, primarily those who had converted to Christianity and lived closer to the white settlements. The non-treaty bands, including Chief Joseph’s Wallowa band, White Bird’s band, and Looking Glass’s band, vehemently refused to acknowledge its legitimacy. For them, land was not a commodity to be bought and sold; it was their mother, their spiritual and cultural anchor. Chief Joseph, whose Nez Perce name was Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it (Thunder Rolling Down the Mountain), famously declared, "The earth is our mother. We cannot sell our mother."

The inevitable clash arrived in the spring of 1877. General Oliver O. Howard, known as "the Christian General," was tasked with forcing the non-treaty bands onto the drastically reduced reservation. He issued an ultimatum: move to the reservation within 30 days or face military action. The chiefs, recognizing the futility of resistance against the overwhelming might of the U.S. Army, reluctantly agreed. They gathered their people, their horses, and their meager possessions for the painful journey to Lapwai.

But fate, or perhaps desperation, intervened. On their way to the reservation, a small group of young warriors, fueled by grief and anger over the murder of a tribal member and the theft of their horses, retaliated by killing several white settlers. The die was cast. The Nez Perce knew there was no turning back. Their only option was to fight for their freedom or flee to Canada, where they hoped to find asylum with Sitting Bull’s Lakota people, who had sought refuge there after the Battle of Little Bighorn the previous year.

Thus began the epic migration. The journey can be broken down into several harrowing stages:

1. The Flight and First Victories (June 1877):

From their gathering place near Tolo Lake, the Nez Perce began their desperate flight. General Howard immediately dispatched troops to intercept them. The first major engagement occurred on June 17, 1877, at White Bird Canyon. In a stunning display of tactical brilliance, the Nez Perce warriors, led by Ollokot, Chief Joseph’s younger brother, ambushed and decisively defeated a U.S. Cavalry unit, killing 34 soldiers with no Nez Perce casualties. This victory, while boosting morale, sealed their fate: the war was on.

2. The Clearwater Retreat (July 1877):

Following White Bird, the Nez Perce continued their retreat, pursued by Howard’s reinforced army. On July 11-12, they engaged in the Battle of the Clearwater, a two-day standoff where the Nez Perce held their ground against a numerically superior force before executing a masterful tactical withdrawal. They demonstrated an incredible ability to fight defensively while preparing for their next move.

3. The Passage Through Lolo Pass and Bitterroot Valley (July-August 1877):

Realizing they couldn’t indefinitely evade Howard in Idaho, the Nez Perce turned eastward, heading for the rugged Lolo Pass in the Bitterroot Mountains, a traditional route to the buffalo grounds. They built a defensive breastwork known as "Fort Fizzle," effectively blocking Howard’s direct pursuit. Through a combination of cunning and negotiation, they bypassed the fort and descended into the Bitterroot Valley of Montana. Here, surprisingly, some local settlers, recognizing the Nez Perce’s peaceful intentions (they paid for supplies), even traded with them, a brief respite before the storm.

4. The Big Hole Massacre (August 1877):

The brief peace was shattered on August 9 at the Battle of the Big Hole. Colonel John Gibbon, leading troops from Fort Shaw, launched a devastating pre-dawn surprise attack on the sleeping Nez Perce camp. It was a brutal massacre, particularly of women and children. Despite the shock and heavy losses (estimated 60-90 Nez Perce killed, including many non-combatants), the warriors rallied under leaders like Looking Glass and Ollokot, driving Gibbon’s forces back and eventually forcing them to retreat. The Nez Perce buried their dead and continued their harrowing journey, their resolve hardened by grief and rage. This battle underscored the ruthless nature of the conflict and eliminated any lingering hope of a peaceful surrender.

5. The Yellowstone Gauntlet (August-September 1877):

From Big Hole, the Nez Perce pushed southeast, entering the newly established Yellowstone National Park. Their passage through this unique landscape was surreal: they encountered bewildered tourists, captured and released some, and continued to evade U.S. Army detachments converging from all directions. This leg of the journey showcased their incredible endurance and knowledge of the land, navigating geysers, hot springs, and rugged wilderness while still carrying their wounded and sick.

6. The Race for Canada and Bear Paw (September-October 1877):

Leaving Yellowstone, the Nez Perce turned north, racing towards the Canadian border. They had covered over a thousand miles, their horses exhausted, their people weary, starving, and increasingly desperate. The leadership council was often divided, but the collective will to reach freedom remained. They were agonizingly close to their goal when, on September 30, Colonel Nelson A. Miles, leading fresh troops from Fort Keogh, launched a surprise attack at Bear Paw Mountains, just 40 miles from the border.

The Battle of Bear Paw was the final, tragic stand. Caught off guard, the Nez Perce established defensive positions in a freezing, windswept ravine. For five days, they endured a brutal siege, battered by artillery fire and relentless attacks. The weather turned bitterly cold, and many froze to death. Ollokot, Too-hul-hul-sote, and other key leaders were killed. With their numbers dwindling, their supplies exhausted, and their children freezing, Chief Joseph, after consulting with the remaining leaders, made the agonizing decision to surrender.

On October 5, 1877, Chief Joseph delivered one of the most poignant speeches in American history, his words resonating with profound sorrow and a father’s love for his suffering people:

"Tell General Howard I know his heart. What he told me before, I have in my heart. I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. Looking Glass is dead. Toohoolhoolzote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led on the young men is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food; no one knows where they are – perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children, and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever."

The surrender, however, did not bring the promised return to their homeland. Instead, the surviving Nez Perce were exiled, first to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and then to a reservation in Oklahoma, a starkly different climate that claimed many lives. It was not until 1885 that some, including Chief Joseph, were allowed to return to the Pacific Northwest, though not to their beloved Wallowa Valley but to the Colville Reservation in Washington. Chief Joseph died there in 1904, a prisoner of war to the end, his heart broken by the loss of his people and his land.

The Nez Perce migration of 1877 stands as a testament to extraordinary courage, strategic brilliance, and the indomitable human spirit. It exposed the deep injustices inherent in America’s westward expansion and the tragic consequences of broken treaties. While the Nez Perce did not achieve their desired freedom, their epic journey captured the imagination of a nation and the world, transforming Chief Joseph into an international symbol of Indigenous resistance and dignity. Their trail, marked by sacrifice and perseverance, remains an unbroken testament to a people who fought for their right to exist, reminding us of the profound costs of conquest and the enduring legacy of those who walked the path of defiance.