The Mirage of Cíbola: Coronado’s Epic Quest and the Forging of American Legend

America, a land woven from grand narratives and whispered myths, holds within its vast expanse countless tales that shape its identity. From the stoic sagas of indigenous peoples to the audacious quests of European explorers, these legends are not merely historical footnotes but living embers that continue to glow in the national consciousness. Among the most compelling of these is the epic, and ultimately tragic, journey of Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, a Spanish conquistador whose relentless pursuit of fabled golden cities inadvertently mapped a significant portion of what would become the American Southwest, forever etching his name into the continent’s legendary tapestry.

In the early 16th century, fresh from the breathtaking conquests of the Aztec and Inca empires, Spain’s appetite for gold was insatiable. Rumors, fueled by distorted accounts and fervent imaginations, began to circulate of seven magnificent cities, known collectively as Cíbola, located somewhere north of New Spain (modern-day Mexico). These cities, it was said, rivaled the legendary wealth of Tenochtitlan and Cuzco, their streets paved with gold and their inhabitants adorned with precious jewels. This tantalizing prospect ignited the ambition of Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, a young, well-connected governor of Nueva Galicia, who saw in Cíbola not just unimaginable riches, but immortal glory.

The genesis of the Cíbola myth can be traced to Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and his companions, who, shipwrecked in 1528, spent eight harrowing years traversing the continent as captives and healers among various indigenous tribes. Upon their miraculous return, they spoke of vast lands and powerful peoples to the north, though their accounts of great wealth were vague. It was the subsequent report of Fray Marcos de Niza, a Franciscan friar dispatched to verify Cabeza de Vaca’s claims, that truly set the legend ablaze. Fray Marcos, claiming to have seen Cíbola from a distance – though he never actually entered it – described a city "larger and richer than Mexico City itself," its houses adorned with turquoise and its people possessing great quantities of gold. This exaggerated, almost certainly fabricated, testimony was the spark that ignited one of history’s most ambitious and ill-fated expeditions.

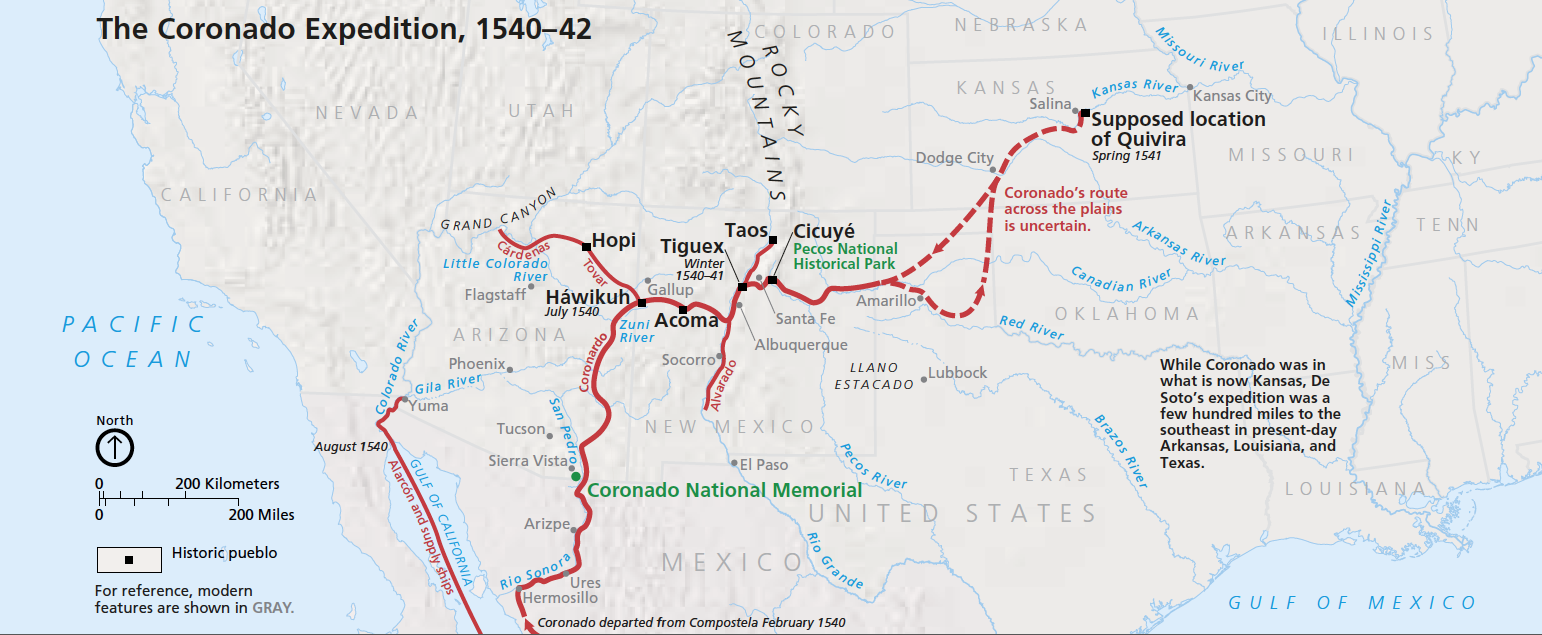

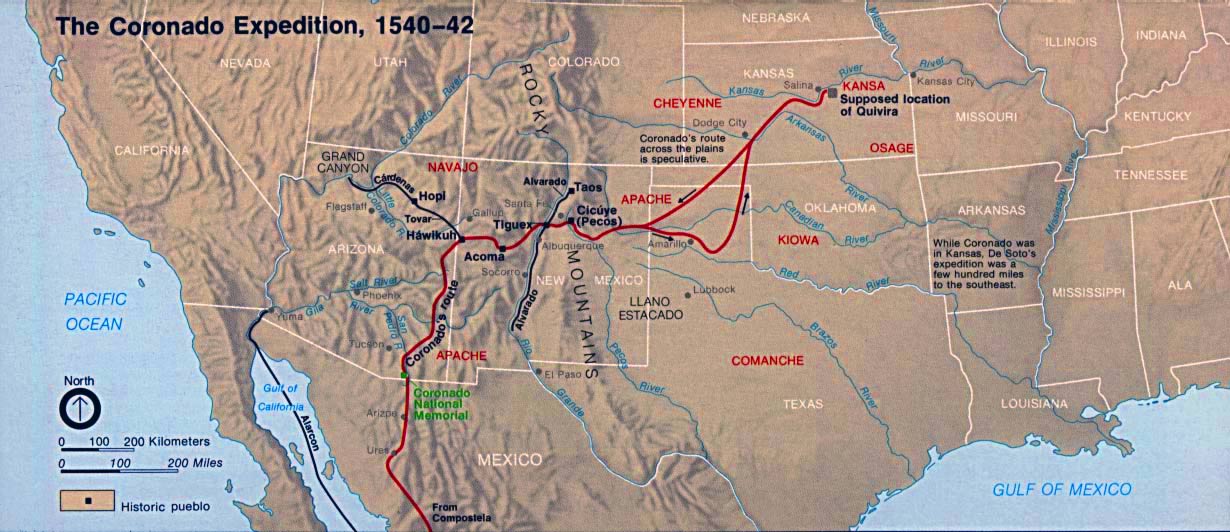

Coronado, eager to secure his legacy and fill Spain’s coffers, spared no expense in assembling his force. In 1540, a formidable expedition of around 300 Spanish soldiers (many of them young men of noble birth), nearly 1,000 indigenous allies, over 1,500 horses, and thousands of sheep, cattle, and mules departed from Compostela. It was a logistical marvel for its time, a veritable moving city with the sole purpose of finding gold. The sheer scale of the undertaking underscored the immense belief in Fray Marcos’s report and the magnetic pull of the Cíbola myth. This was not merely an exploration; it was an invasion of a promised land, fueled by avarice and a profound sense of manifest destiny.

The journey north was arduous from the outset. Scorching deserts, unforgiving mountains, and the constant threat of dwindling supplies tested the resolve of even the most hardened soldiers. The expectation of immediate wealth began to clash violently with the harsh reality of the landscape. After months of relentless travel, the vanguard of Coronado’s army finally reached what they believed to be the first of the Seven Cities – Hawikuh, a Zuni pueblo in present-day New Mexico. Their anticipation, however, quickly turned to bitter disappointment. Hawikuh was no golden metropolis; it was a humble village of mud and stone, its inhabitants bravely defending their homes with bows and arrows, not displaying vast treasures.

Coronado, wounded in the initial skirmish, later recounted his disillusionment: "It is a small, crowded village, looking as if it had been crumpled all up together. There are not more than 200 houses in it… they are not at all such as was described by the friar." The stark reality shattered the golden illusion, but the quest for wealth, once ignited, was not easily extinguished. Perhaps, Coronado reasoned, Fray Marcos had merely seen a different city, or perhaps the true Cíbola lay further beyond.

From Hawikuh, the expedition fanned out, exploring the surrounding regions. Captain García López de Cárdenas, leading a small contingent, became the first European to gaze upon the awe-inspiring chasm of the Grand Canyon, a natural wonder far more magnificent than any imagined city of gold. Another group journeyed west, encountering the Hopi people and their ancient mesa-top villages. Throughout these encounters, the Spanish encountered sophisticated indigenous cultures, some wary, some hostile, but none possessing the glittering riches they sought. The clash of cultures was often violent, with the technologically superior Spanish frequently resorting to force to obtain food and subjugate native populations, leaving a legacy of resentment and devastation.

The expedition’s hopes were rekindled by a Plains Indian known as "the Turk." This enigmatic figure, possibly from the Wichita people, told tales of a land called Quivira, far to the east, where a powerful king slept under a tree hung with golden bells, and where rivers teemed with fish as large as horses. Driven by this new, even grander promise, Coronado led a smaller, faster contingent eastward across the vast, treeless expanse of the Great Plains. Here, the Europeans encountered immense herds of buffalo, a sight that must have been both astonishing and overwhelming. "I reached some plains," Coronado wrote, "so vast that I did not find their end everywhere I went… where I saw a great multitude of cows, as many as the mountains of Switzerland."

The journey across the plains was a test of endurance unlike any they had faced. The endless horizon, the lack of landmarks, and the sheer scale of the landscape disoriented them. After weeks of travel, they finally reached Quivira, in what is now central Kansas. Once again, their hopes were dashed. Quivira was not a city of gold but a collection of humble grass huts inhabited by the Wichita people. The "Turk" had clearly fabricated his stories, likely to lead the Spanish away from his own people or to their doom. Enraged by the deception and the immense hardship it had caused, Coronado ordered the Turk’s execution.

Dejected and with dwindling resources, Coronado decided to turn back. His return journey in 1542 was a bitter retreat. He arrived back in Mexico a broken man, both physically and financially ruined, having spent his entire fortune on the expedition. He faced charges of cruelty to indigenous people and incompetence, though he was ultimately acquitted. Coronado died in relative obscurity a few years later, his dream of Cíbola unfulfilled.

Yet, Coronado’s "failure" was, in a profound sense, a success. His expedition, despite its misguided premise, provided Europe with the first detailed glimpse of the American Southwest and parts of the Great Plains. His chroniclers, like Pedro de Castañeda de Nájera, meticulously documented the geography, flora, fauna, and, crucially, the diverse indigenous cultures they encountered. They dispelled the myth of golden cities in the north, but in doing so, they revealed a continent of immense natural beauty and rich human heritage.

The legend of Coronado is not merely a tale of a gold rush gone wrong; it is a foundational myth in the American story, a narrative of ambition, illusion, and discovery. It highlights the clash between European expansionism and indigenous sovereignty, the devastating impact of foreign diseases and violence, and the enduring human capacity for both grand vision and profound self-deception. It speaks to the allure of the unknown, the power of a good story, and the often-harsh realities that lie beyond the horizon of dreams.

Today, as one traverses the sun-drenched landscapes of New Mexico, Arizona, and Kansas, the ghost of Coronado’s expedition lingers. The ancient pueblos still stand, silent witnesses to his passage. The Grand Canyon continues to inspire awe, a testament to a discovery made in the pursuit of something entirely different. The legend of Coronado reminds us that not all treasures glitter, and that sometimes, the greatest discoveries are not what we seek, but what we find along the way – a deeper understanding of the land, its people, and the enduring power of the human spirit to chase even the most elusive of dreams. His epic quest for a mirage of gold ultimately revealed the true, multifaceted legend of America itself.