Whispers from the Sands: Francisco Garcés and the Unsung Legends of America

The tapestry of American legends is woven with threads of daring pioneers, intrepid explorers, and larger-than-life figures who shaped a continent. From the stoic endurance of the mountain men to the audacious spirit of the forty-niners, these tales often conjure images of a nascent nation pushing westward, guided by Manifest Destiny. Yet, beneath this familiar narrative lies a deeper stratum of legends, figures whose journeys predate the Stars and Stripes, whose courage carved pathways through the wilderness long before Lewis and Clark set foot in the Louisiana Purchase. Among these unsung heroes, whose story remains a whisper in the vast American historical echo chamber, is Francisco Garcés – a Franciscan friar whose relentless pursuit of discovery and spiritual connection illuminated the American Southwest in the late 18th century, leaving behind a legacy as profound as it is tragically overlooked.

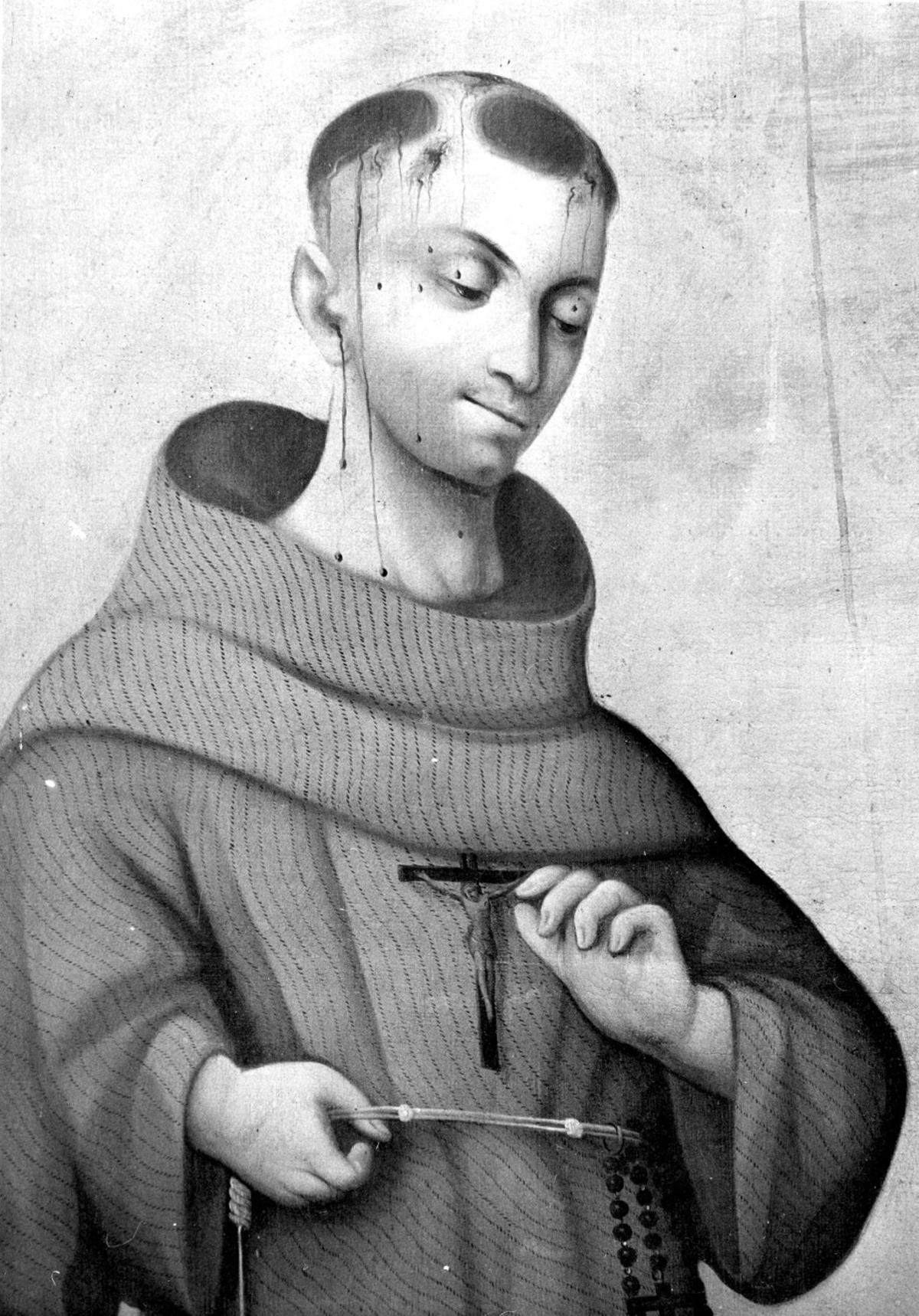

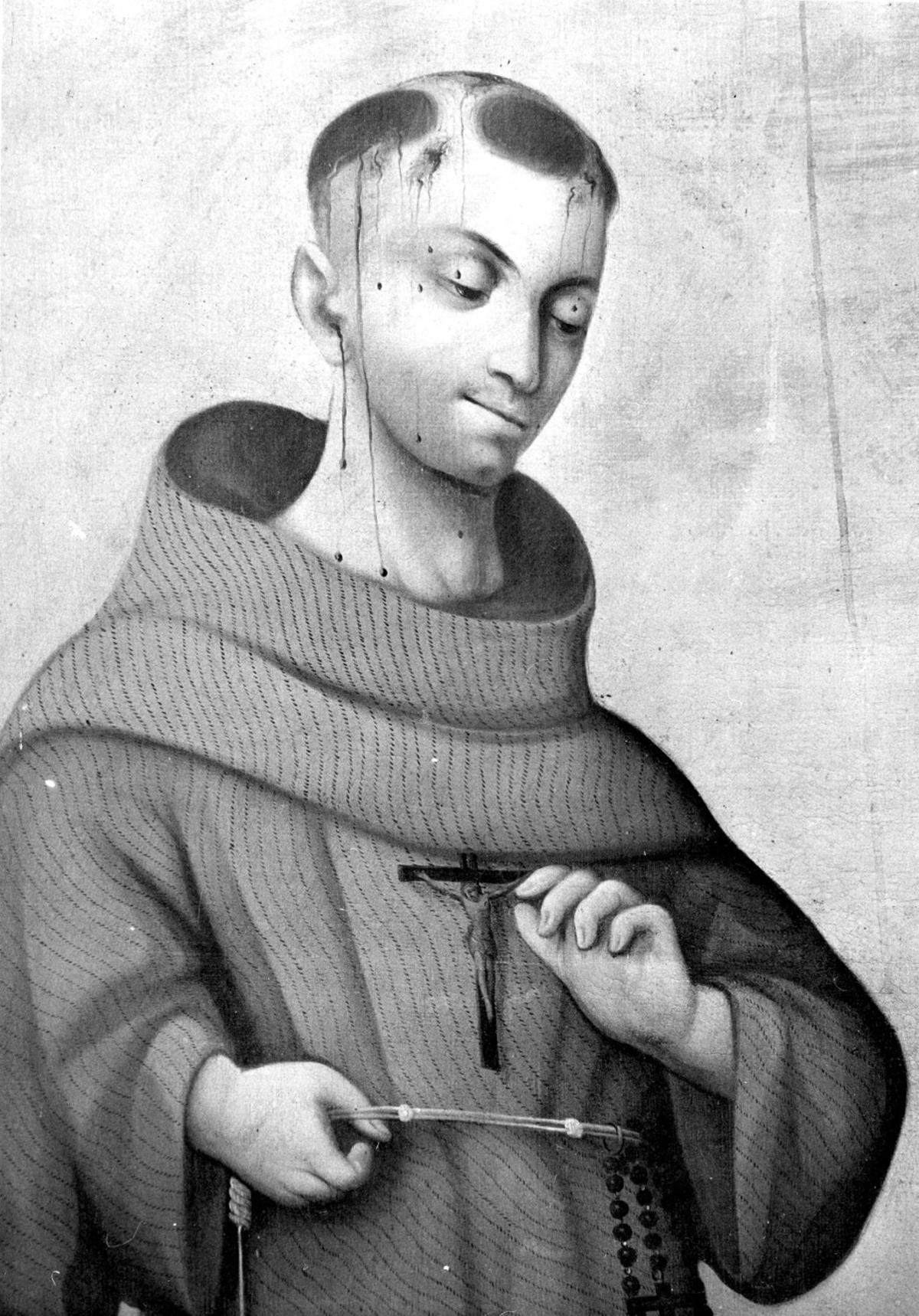

Born in Morata de Jalón, Spain, in 1738, Francisco Garcés was no ordinary missionary. He arrived in New Spain (modern-day Mexico) in 1768, destined for the newly established Mission San Xavier del Bac, just south of present-day Tucson, Arizona. While many of his contemporaries focused on establishing fixed settlements and converting indigenous populations through traditional means, Garcés harbored an insatiable wanderlust and a unique approach to evangelization. He believed in reaching people where they lived, on their own terms, often foregoing military escorts and embracing the harsh realities of the untamed frontier. This unconventional method, driven by a profound faith and an extraordinary capacity for empathy, would transform him from a simple friar into one of North America’s most remarkable, if forgotten, explorers.

Garcés’s legendary status is not built on mythical feats of strength or impossible tales of derring-do, but on the sheer, verifiable scope of his travels and the groundbreaking nature of his interactions. He was, in many respects, a cartographer of the soul and the landscape. Over the course of a mere decade, he embarked on no fewer than five major expeditions, often alone or with only a handful of Native American guides, covering thousands of miles across what would become Arizona, California, and even parts of Nevada. He traversed deserts and mountains where, centuries later, pioneers and prospectors would still struggle, and where even today, the elements remain unforgiving.

His first significant journey in 1770 took him deep into the Gila River country, establishing contact with various Pima and Maricopa communities. This was a prelude to his most ambitious undertakings. Garcés had an almost uncanny ability to learn indigenous languages and adapt to local customs, earning him a level of trust and access rarely afforded to European newcomers. He was known to dress in deerskin, like the natives, and share their humble meals, a stark contrast to the often-imposing presence of Spanish soldiers or other missionaries. This cultural immersion was not merely a tactic; it was integral to his spiritual mission. He documented his encounters with an almost ethnographic precision, describing the customs, languages, and territories of the indigenous peoples he met in his meticulously kept diaries, which remain invaluable historical records.

One of his most significant expeditions began in 1775, when he joined Juan Bautista de Anza’s second overland expedition from Sonora to Alta California. Anza’s goal was to establish a land route to the newly founded mission at San Gabriel (near modern Los Angeles) and explore possibilities for further colonization. While Anza led the main party, Garcés, ever the independent spirit, diverged from the main route, venturing into uncharted territories. It was during this epic journey that he became the first European to cross the vast, desolate Mojave Desert, reaching the Mohave villages along the Colorado River. His encounter with the Mohave people was a testament to his unique diplomacy. He spent weeks among them, learning their language and customs, before continuing westward.

From the Colorado River, Garcés pushed further, eventually reaching the San Gabriel Mission, becoming the first European to travel overland from the Colorado River to the California coast and back. But his journey wasn’t over. He then turned north, traveling up the San Joaquin Valley, exploring routes that would later become critical pathways for American expansion. His insatiable curiosity and commitment to understanding the land and its people led him to places no European had ever seen. He likely reached the vicinity of the Grand Canyon’s South Rim, a full century before John Wesley Powell’s famous exploration. He attempted to reach the Hopi mesas, a journey of immense peril, but was turned back by the wary Hopi, who had already experienced the brutal realities of Spanish conquest in other regions.

Garcés’s journals are more than just travel logs; they are windows into a forgotten world, offering invaluable insights into the pre-colonial Southwest. He meticulously recorded not just geographical features, but also the flora, fauna, and, crucially, the complex social and political landscapes of the numerous Native American nations he encountered: the Quechan (Yuma), Mohave, Havasupai, Paiute, and more. His descriptions often reveal a profound respect for their cultures, a stark departure from the often-condescending views of many European chroniclers of the era. He noted the rich agricultural practices of the riverine tribes, their intricate trade networks, and their sophisticated understanding of their environment.

Yet, despite his unique approach, Garcés was ultimately a product of his time and a representative of a colonizing power. His mission, while deeply personal and spiritual, was also intertwined with the broader imperial ambitions of Spain. The Spanish crown sought to expand its territories, protect its northern frontier from other European powers (like the Russians and British), and secure vital overland routes. Garcés’s detailed maps and ethnographic data were invaluable to these efforts, even if his personal vision was primarily one of peaceful conversion.

This inherent tension between his empathetic evangelism and the realities of empire would ultimately lead to his tragic end. In 1779, Garcés returned to the Yuma (Quechan) territory along the Colorado River, this time not as a lone friar but as part of a Spanish attempt to establish a new mission and presidio. The Spanish plan, however, failed to respect the Quechan’s traditional lands and resource management. Spanish settlers, soldiers, and livestock encroached upon vital agricultural areas, disrupting the delicate ecological balance and challenging Quechan sovereignty. The Quechan, led by their chief, Salvador Palma, had initially welcomed Garcés, but grew increasingly resentful of the Spanish presence.

On July 17, 1781, simmering tensions erupted into what became known as the Yuma Uprising or the Quechan Revolt. The Quechan attacked the Spanish settlements, killing soldiers, settlers, and, tragically, four Franciscan friars, including Francisco Garcés. He was martyred, not by the wilderness he so bravely navigated, but by the clash of cultures he had so earnestly tried to bridge. His death marked a significant setback for Spanish expansion in the region and served as a brutal reminder of the complexities and dangers of intercultural contact during the era of colonization.

Why, then, does the legend of Francisco Garcés not resonate as loudly as those of Daniel Boone or Davy Crockett, or even Lewis and Clark? Part of the reason lies in the historical lens through which American history has traditionally been viewed. The dominant narrative often begins with the English colonies and the westward expansion of the United States, sidelining the rich, complex Spanish colonial period that preceded it. Garcés’s journals were written in Spanish, further limiting their accessibility to a broader American audience. Furthermore, his story lacks the clear-cut heroics of military conquest or the romanticized individualism of the lone frontiersman, instead offering a more nuanced tale of spiritual devotion, cultural immersion, and tragic misunderstanding.

Yet, Francisco Garcés is a legend that deserves to be rediscovered and celebrated. His journeys represent an extraordinary chapter in the exploration of North America, a testament to human endurance, cross-cultural diplomacy, and the profound impact of individual will. He was a pioneer in every sense of the word, a bridge-builder who saw the humanity in every person he met, regardless of their origin. His detailed records provide an unparalleled glimpse into the world of the indigenous peoples of the Southwest before the full tide of European settlement irrevocably altered their lives.

In a nation that prides itself on its spirit of discovery and its diverse heritage, the story of Francisco Garcés offers a crucial counter-narrative, a reminder that the legends of America are far more intricate and multi-faceted than commonly understood. His whispers from the sands of the Mojave and the banks of the Colorado tell of a time when the continent was still largely unknown to Europeans, and when one man, driven by faith and an insatiable curiosity, dared to venture where no one else had, leaving behind a legacy that continues to inspire and inform, if only we choose to listen. His legend is not just about where he went, but how he went, and the enduring lessons of understanding and respect he embodied in a world on the brink of profound change.