Echoes from the Frontier: The Warren Wagon Train Raid and the Forging of American Legends

The American West, a crucible of dreams and despair, of boundless opportunity and brutal conflict, remains fertile ground for the legends that define a nation. From the rugged individualist cowboy to the stoic Native American warrior, these figures and the events they shaped are etched into the national consciousness. Yet, beneath the romanticized veneer often lies a complex, often tragic, history where different truths clashed, and the lines between hero and villain blurred. One such pivotal, yet often overlooked, event that starkly illuminates this clash, dramatically altering the course of U.S. Indian policy and leaving an indelible mark on the frontier narrative, is the Warren Wagon Train Raid of May 1871.

This wasn’t just another skirmish on the vast plains of Texas; it was an act of audacious defiance by powerful Kiowa and Comanche chiefs that drew the personal ire of General William Tecumseh Sherman, the architect of the Union’s "total war" strategy during the Civil War. His subsequent actions, born of fury and a desire for decisive justice, would set in motion a chain of events that escalated the Indian Wars and cemented the fate of the Southern Plains tribes.

The Shifting Sands of the Frontier

By the late 1860s and early 1870s, the American frontier was a pressure cooker of competing interests. Manifest Destiny, the belief in America’s divinely ordained expansion across the continent, drove settlers, ranchers, and railroad builders westward. For the indigenous peoples, particularly the Kiowa and Comanche who had for centuries roamed the vast buffalo-rich lands of the Southern Plains, this influx was an existential threat. Treaties, often signed under duress or misunderstood, were routinely broken, their ancestral lands shrinking, their way of life threatened by the decimation of the buffalo herds and the encroachment of white settlements.

The U.S. government, under President Ulysses S. Grant, was attempting a "Peace Policy," advocating for the humane treatment of Native Americans and their assimilation into American society through reservations and education. However, this policy was often undermined by a lack of resources, corruption, and the inherent conflict between the desire for peace and the relentless demand for land. On the ground, the reality was a tense standoff, punctuated by raids and retaliations, as both sides struggled to survive and assert their claims.

The Kiowa and Comanche, renowned for their equestrian skills and fierce independence, viewed the reservations not as havens but as prisons. Led by formidable chiefs like Satanta ("White Bear"), Satank ("Sitting Bear"), and Big Tree (Ado-ete), they continued to launch raids into Texas, seeking horses, supplies, and retribution for perceived injustices. These raids, while devastating to settlers, were seen by the tribes as acts of resistance and a desperate attempt to maintain their freedom and traditional way of life.

The Spark: May 18, 1871

On May 18, 1871, a 10-wagon train, loaded with corn and other supplies, lumbered along the Salt Creek Prairie, near present-day Graham, Texas. It was under contract to transport goods to Fort Richardson, a military outpost meant to protect the burgeoning frontier. The wagons were led by Henry Warren, an experienced freighter, and escorted by a small detachment of 12 soldiers. Unbeknownst to them, they were being watched.

General William Tecumseh Sherman, on an inspection tour of military posts in Texas, had ridden this very road just 24 hours earlier. Accompanied by a small escort, he had passed through the area without incident, albeit with a growing unease about the security of the frontier. This near-miss would prove to be a crucial detail, fueling his personal outrage.

The Kiowa and Comanche war party, numbering over 100 warriors, had been scouting the area, intent on plunder. They had spotted Sherman’s entourage but, according to later accounts, chose not to attack the smaller, heavily armed military party, opting instead for the more vulnerable wagon train they knew would soon follow. This decision, a tactical one at the time, would have catastrophic consequences for their leaders.

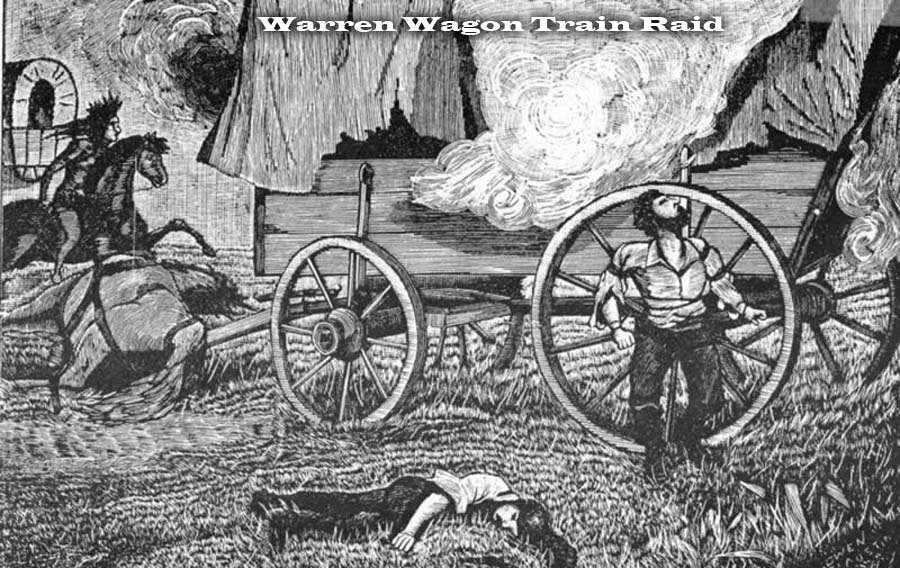

The ambush was swift and brutal. As the wagons entered a wooded area, the warriors, led by Satanta, Satank, and Big Tree, erupted from the tree line with chilling war cries. The surprise was complete. Seven teamsters were killed, their bodies mutilated – a common practice in Plains warfare, intended to count coups and send a clear message. The wagons were looted, set ablaze, and the remaining five teamsters were left for dead, though they miraculously survived. The Kiowa and Comanche made off with 41 mules and a bounty of supplies.

Sherman’s Fury and the Pursuit of Justice

When news of the raid reached General Sherman at Fort Richardson, he was, by all accounts, incandescent with fury. The fact that he had personally traversed that same stretch of road just hours before the attack, and that his own men had been spared only by a twist of fate, galvanized his resolve. This was not merely a frontier incident; it was a personal affront, a challenge to the authority of the U.S. Army.

Sherman immediately dispatched Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie and the 4th U.S. Cavalry, a unit that would become legendary in the Indian Wars, to pursue the raiders. However, the plains offered little in the way of easy tracking. The trail led them to the Fort Sill Indian Agency in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma), where many of the Kiowa and Comanche were supposed to be confined under the terms of the Medicine Lodge Treaty.

At Fort Sill, Sherman confronted Lawrie Tatum, the Quaker agent who, despite his peaceful intentions, struggled to control the increasingly restless tribes. It was Tatum who provided the crucial breakthrough. He identified Satanta, Satank, and Big Tree as the likely culprits, based on intelligence from other tribal members and the sheer audacity of Satanta, who reportedly boasted about leading the raid, even displaying items taken from the wagon train.

The Arrests and Satank’s Defiance

Sherman, accompanied by a heavy military escort, summoned the chiefs to a council at Fort Sill. In a dramatic and tense confrontation, he accused Satanta, Satank, and Big Tree of the raid and ordered their arrest. This was an unprecedented move; arresting powerful chiefs within the confines of an agency was a dangerous gamble, risking a general uprising.

Satanta, with characteristic defiance, openly admitted his role, stating, "I am Satanta, and I led the attack. I am a warrior, and I did what I thought was right for my people." His admission, intended as a boast of his prowess, sealed his fate. Satank, an older, revered warrior, also present, knew his time was up.

The arrests were met with a storm of protest from other warriors, who surrounded the fort, demanding the release of their leaders. Sherman, however, held firm, backed by the overwhelming firepower of his troops. As the three chiefs were being loaded into wagons for transport to Jacksboro, Texas, for trial, Satank made a final, defiant stand.

Singing his death song, a traditional Kiowa farewell, Satank reportedly declared, "I shall never go to Texas," and pulled a knife, attacking one of his guards. The soldiers reacted swiftly, shooting him dead in the wagon. His body was left by the roadside, a stark symbol of the brutal realities of the frontier. Satank’s death, a powerful moment of resistance, became a legend among his people, cementing his place as a warrior who preferred death to captivity and humiliation.

The Trial and its Aftermath

The trial of Satanta and Big Tree in Jacksboro, Texas, in July 1871, was a landmark event. It was the first time Native American chiefs were tried in a civilian court for crimes committed in the context of warfare, rather than through military courts or treaty negotiations. The trial garnered national attention, framed by the press as a victory for justice against "savagery."

The defense argued that the chiefs were prisoners of war and should not be tried in a civilian court, and that their actions were a response to the injustices inflicted upon their people. The prosecution, however, presented compelling evidence, including the testimony of the surviving teamsters and Satanta’s own admission. The jury found both Satanta and Big Tree guilty of murder, and they were sentenced to hang.

This verdict, while satisfying to the frontier settlers and the military, created a political firestorm. Quaker humanitarians and others concerned about the "Peace Policy" lobbied heavily for clemency. Texas Governor Edmund J. Davis, fearing that executing the chiefs would provoke a wider war and undermine the fragile peace efforts, commuted their sentences to life imprisonment, over Sherman’s strenuous objections.

Satanta and Big Tree were imprisoned in the state penitentiary at Huntsville, Texas. Their imprisonment, however, did not bring peace. Raids continued, and the Kiowa and Comanche demanded the release of their leaders. In 1873, in a controversial move, Governor Davis paroled Satanta and Big Tree, hoping to secure peace through negotiation. This decision was met with outrage by many Texans, who felt betrayed.

The gamble ultimately failed. Satanta, a man of profound pride and a deep connection to his people’s traditional way of life, found it impossible to adapt to reservation life or the white man’s terms of peace. He was rearrested in 1874 for violating his parole by participating in the Red River War, a major conflict that finally crushed the last vestiges of Kiowa and Comanche resistance. Imprisoned again at Huntsville, Satanta, seeing no hope for freedom, committed suicide in 1878 by throwing himself from a prison window. Big Tree, by contrast, lived a long life, eventually becoming a respected figure on the reservation, converting to Christianity, and advocating for his people.

A Legacy Forged in Conflict

The Warren Wagon Train Raid and its dramatic aftermath left an enduring legacy on the American frontier. It irrevocably shifted U.S. Indian policy, moving away from the conciliatory aspects of the "Peace Policy" towards a more aggressive military solution. General Sherman, convinced that only force could bring order to the plains, unleashed the full might of the U.S. Army, leading to the Red River War and the eventual confinement of the Southern Plains tribes on reservations.

The event became a stark reminder of the clashing worlds: the pioneers striving for a new life, the military striving for control, and the indigenous peoples fighting for survival and their ancestral heritage. Satanta and Satank became figures of defiant resistance for their people, while for many white settlers, they were symbols of "savagery" that needed to be subdued.

In the tapestry of American legends, the Warren Wagon Train Raid serves as a potent, albeit somber, thread. It speaks to the brutal realities of westward expansion, the inherent tragedy of conflicting claims to land and liberty, and the complex process by which a nation builds its identity. It reminds us that legends are not always tales of unblemished heroism, but often stark narratives of conflict, sacrifice, and the enduring echoes of a past where different visions of freedom collided on the vast, unforgiving frontier.